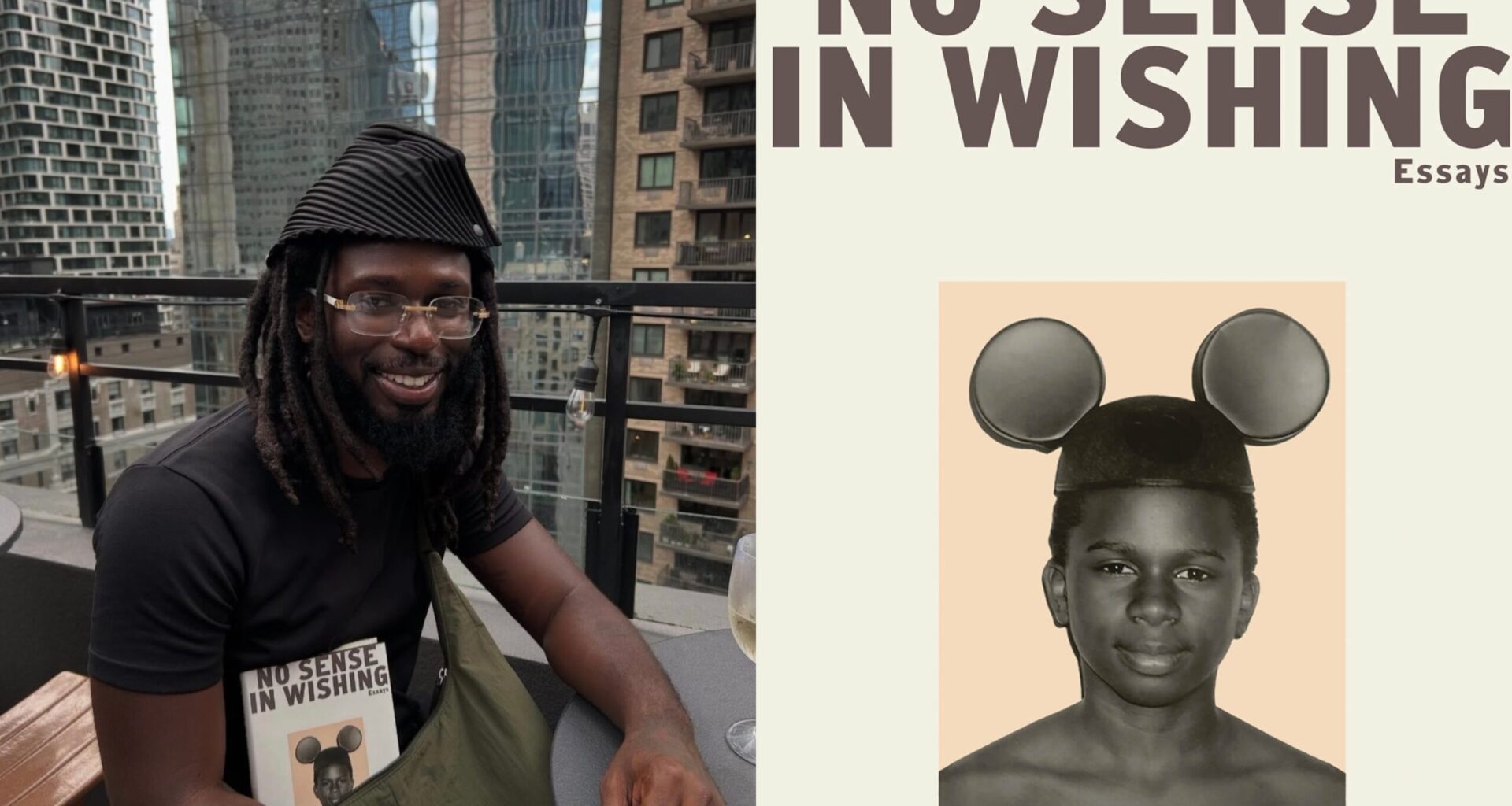

In Lawrence Burney’s debut book, No Sense in Wishing (out now by Atria Books), Baltimore mostly takes center stage, as the culture critic, publisher, and East Baltimore native dives into a harbor of reflections on everything from the African diaspora to hip-hop to the intimacy and fellowship that comes from picking a pile of steamed crabs.

Throughout the collection of essays, Burney mines his memory in a search for himself—exploring interactions with the sounds, scenes, travels, crafts, and people that made him who he is today.

A self-proclaimed intentional music listener, Burney is widely known as the founder of DIY zine True Laurels, as well as a music journalist whose work has been published nationally by the likes of Vice, The Fader, New York Magazine, Pitchfork, and recently Rolling Stone. Locally, he’s also contributed to this magazine and The Baltimore Banner.

Ahead of his East Coast book tour—which kicked off this week, with stops planned at Red Emma’s in Waverly on July 11, The Buzzed Word in Ocean City on July 16, and The Ivy Bookshop in Mt. Washington on July 31—we interviewed Burney by phone about the new title.

The conversation delved into how Baltimore has shaped his voice, what sparked this project (it was inspired by a 2003 documentary, Girlhood, about two young women from Baltimore caught up in the juvenile justice system, which left a lasting impression on him) and the continued impact of True Laurels.

Who is Lawrence Burney? Where are you from? Who are your people? What should locals just being introduced to your work know about you?

Well, I grew up on the east side and bounced to a couple neighborhoods. But when I was young, I lived on Aisquith Street in the Coldstream area. It’s like near Kirk Avenue, if you know where that is. Not too far from the Black side of 25th Street, like once you pass Greenmount. So it’s like a little 7/11 over there on 25th Street, like near Harford Road, that area. And then I went to the Belair-Edison neighborhood, and then I guess you would say Northwood, near Morgan.

I come from a family, at least on my mother’s side, of people who are pretty creatively inclined. So I have my mother [Victoria Adams-Kennedy], who used to do music. She’s a writer. She also runs Zora’s Den, trying to empower Black women writers. Then my uncle was an artist based in New York. That’s my mother’s younger brother, my uncle, [multidisciplinary artist and founder of The Last Resort Artist Retreat] Derrick [Adams]. Throughout my family, there are people that have always kind of tried their hand at some form of creativity. So it wasn’t a far-fetched thing for me. I didn’t necessarily think that’s what I would pursue. But I come from a family that’s pretty supportive of those types of things.

How has place shaped you as a writer? What does Baltimore lend to your writing?

I’m very much a Baltimore person, so I understand the world largely based around my experiences growing up here. I feel like my interest in counter culture, or scenes and cultures that are not typically celebrated on a wide scale, comes from the fact that I’m from a place that’s also pretty overlooked and oversimplified. So I always know there’s more under the surface than what the wider population might know.

I’m always trying to engage those types of places, like places that might be disregarded or misunderstood or oversimplified. Those are the places that tend to excite and interest me, and I think it’s because I’m from one of those places. Because of how Baltimore is framed, I’m super sensitive to anti-Black ideas of people or a city. I’m always trying to dismantle those types of categorizations of any place, because I think Baltimore is one of those places that just gets the short end of the stick very often, in so many different ways, but especially people’s perception of it, and the people that come from here.

You’ve been a vital voice in the local arts scene for more than a decade now. Why did you feel now was the right time to write a book—and why this book in particular?

It’s actually not even that deep. My agent reached out to me in 2021. I had no plans of writing a book, but he hit me up, saying that he enjoyed my work, and that he wanted to know if I would consider writing a book. It felt like this was a good sign. Somebody that’s offering their assistance to get me through the door of the publishing industry. I felt I should take advantage of it. It took me a little while to figure out what the book was going to be like. The book that I ended up writing wasn’t the first idea I had for a book, but I would say around, probably 2023 is when I started actually understanding it. Late 2022 is when I started actually putting together.

What can readers expect from the book?

I feel like I’m able to weave in personal narrative with cultural criticism, with a little bit of history. I think I pride myself on [amplifying] lesser known artists or things. So there are a lot of recommendations for music and films in this book, too.

Who would you say No Sense in Wishing is for? What’s the intended impact?

I think for the most part, like, music lovers, people who are interested in history, young people who are trying to navigate their journeys to self discovery—I would say those are probably like the main audiences that are going to [relate]. And educators of young people. I met a lot of teachers yesterday [at the Planet Word Museum in Washington, D.C.] that were interested.

But the thing with a book is you just never know. There are people who are going to read the book who didn’t grow up like me listening to Three 6 Mafia. But I think everybody can relate to encountering forms of cultural production that leave lasting impressions on them. So I think that’s the universal appeal of it. I think there’s a lot of entry points in this book, and, as things go, you can kind of bounce around however you desire.

What’s your favorite essay in the book?

A love letter to steamed crabs piled onto a bed of newspaper.

You’ve published more than 14 issues of True Laurels, a print magazine you founded that is known for its diaries, interviews, profiles, and photo essays spotlighting regional artists. How did the process of putting together a book compare to making True Laurels? In what ways did it feel similar—or completely different?

I would say the book gave me the space to extend. Magazines just don’t typically run super long stories. And also True Laurels is all pretty much me. I spearheaded that whole thing, so even when I have other people involved, it’s me. From the photographers to the other writers, to the designer, to who prints it—all of that is my own doing. So it happens much faster. [For the book], since I have a publisher, there’s a lot of different hands in the pot. True Laurels would appear to be more collaborative, but I would say that writing a book is actually more collaborative because you’re kind of going back and forth with other people.

You’ve done so much to amplify Baltimore’s arts community throughout the years. Any advice for emerging artists on telling their own stories?

I think the most important lesson I’ve learned, I mean, there’s a few, but, for one, you should try to travel. And that doesn’t mean internationally. Could be to another city, another town, another state, because those conversations that you have with people outside of your particular hometown will expand your perception. There’s a lot of points of connectivity that could be identified.

But the most important thing is to kind of just stay persistent. Really, [you] just can’t quit. I think sometimes, along the way, people get frustrated that things aren’t moving as fast as they would like them to move, or they’re not breaking out in a way that they would like to. But a lot of times, people are pretty close to where they should be, and I think that sense of discouragement makes people quit or drop off because they’re not getting the reception that they want.

But if you stick at it, and you stay dedicated to your craft and bettering yourself and just absorbing things that are informing the work, I think you tend to learn where you need to land. If I would have just focused on staying in Baltimore and telling Baltimore stories, I don’t think things would scale the way that they have for me.

Alanah Nichole Davis M.A. is an award-winning writer and regular contributor to Baltimore. This Maryland Institute College of Art alum and mother of two loves Baltimore’s arts, music, festivals, cocktails, and any good meme or reason to celebrate.