The aspirational kitchen of the 21st century, as seen on Instagram, TikTok and other digital platforms, is unmoored from context as we once knew it. Cuisine, as is traditionally understood, grew out of culture and geography. It emerged from the grain of life — how people worked, the elements they battled — and it was watered and nourished by what they valued — seasonings, spices and ingredients that were sometimes so prized that they led to wars of conquest, bloodshed, slavery and great explorations. On the ever-widening sliver of the world that is the Internet, this context is missing. Neither culture nor geography determines the contents of your refrigerator, and as to rare or vanishing flavours — why, those can now be synthesised in a food chemist’s lab! (“Truffle” oil, anyone?) In the 21st century, those of us who can afford do, eat what we please, when we please, liberated from the old forces that determined what was a staple and what could only be a luxury

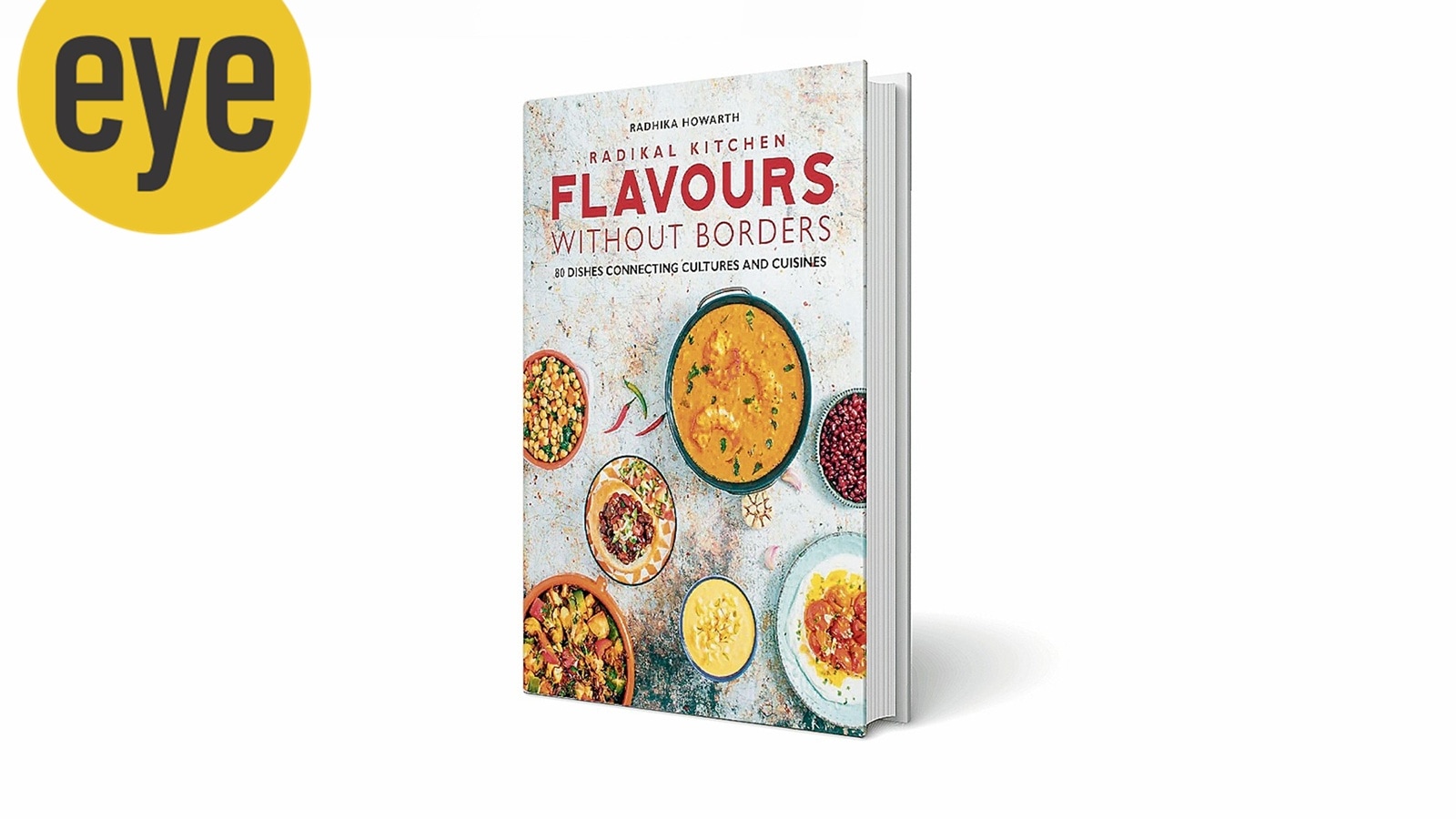

In ‘Flavours without Borders’, Radhika Howarth works backwards, from the diverse origins of today’s pantry essentials — oyster sauce and fenugreek seeds, gochujang and sundried tomatoes — to the historical confluences that led us to this moment. From the Silk Road and the Spice Route to the Buddhist Trail in Southeast Asia and the Moorish rule in Spain, Haworth examines the many kinds of food that we, the global citizens of today, know and love well. Inspired as much by the “United Nations council of flavours” that her own multicultural extended family is, as by her life in the UK with its “vibrant, dynamic and culturally diverse society”, Howarth is a cook of the Instagram age.

In her book, Haworth has set herself the task of tracing the journey of a handful of ingredients and dishes across cultures, an endeavour that uncovers forgotten stories and long-ignored connections between different parts of the world. Take the samosa, whose origins can be traced back to Persian literature of the 11th century and whose most well-known variation — the “classic” variation — is the one found in tea shops, canteens and homes in India (here also, though, fillings and size vary across regions). What connects the three recipes Haworth features in her book — the Uzbek Samsa, Punjabi Samosa and Tanzanian Sambusa — beyond the shape of the food and the broad concept of a stuffed pastry? How did this food travel from West to Central to South Asia and to East Africa? Or take atho noodles, a popular street food in North Chennai: What can it tell us about the historical connections between communities in southern India and Myanmar?

All that, however, is history. It is in the final section of the book that the reader encounters Haworth’s vision of the future, with recipes like Coconut Sambal Spaghetti and Mushroom Do Pyaaza Crostini. These dishes are her riposte to those who insist on “authenticity”, on food that is “uncontaminated” by the forces of history. In challenging dearly-held ideas about how a certain dish “should” be prepared and what ingredients are allowed, Haworth invites readers to refocus their attention on what really matters: What the food they eat tastes like and how it makes them feel.