For years, under the banner of combating human trafficking, the European Border and Coast Guard Agency, commonly known as Frontex, collected personal data from migrants upon their arrival to Europe. This was done via covert interrogations that lacked basic legal safeguards.

Between 2016 and 2023, the agency illegally transferred the data of more than 13,000 people to the European Union Agency for Law Enforcement Cooperation (Europol). There, the data was stored in criminal intelligence files for use in EU police investigations. An investigation by Le Monde, Solomon – a non-profit based in Greece – and EL PAÍS based on hundreds of pages of internal documents and interviews with data protection experts and lawyers reveals the involvement of Frontex and Europol in opaque and legally questionable practices. These have led to the criminalization of migrants and the EU-based activists who assist them or have been in contact with them.

The border agency was forced to change its data transfer protocols following a report by an independent EU body that deemed these practices to be unlawful.

“My whole life was in that police file: my relatives, my calls to my mother, even false details about my sex life. They wanted to portray me as a promiscuous lesbian, using morality to make me look suspicious,” says Helena Maleno, 54, a Spanish human rights activist. She was targeted by law enforcement because of her work informing authorities about people in danger trying to reach Europe by sea. Criminal investigations launched more than a decade ago by authorities in Spain and Morocco reveal the extent of the police siege around her.

Helena Maleno, human rights activist.Javier Sánchez Salcedo

Helena Maleno, human rights activist.Javier Sánchez Salcedo

The file on Maleno compiled by the Spanish National Police included, among other things, three Frontex documents containing details of interviews conducted by European agents with migrants who arrived by boat in Spain between 2015 and 2016. The reports, accessed by this investigation, included information (such as her Facebook account) that presented Maleno as a suspect in human trafficking. The Spanish National Police obtained these reports from Europol’s criminal database in late 2016.

For years, human rights workers have warned of attempts, often made on flimsy legal grounds, to criminalize irregular migrants, along with EU citizens who provide them with assistance at European borders. Hundreds of migrants or human rights activists are detained each year, accused of facilitating irregular immigration.

Helena Maleno certainly isn’t the only person to have faced this problem. Norwegian citizen Tommy Olsen and Austrian citizen Natalie Gruber, both well-known activists, discovered that information about their activities also showed up in Europol’s criminal intelligence database.

On the hunt for information

The first suspicions about Frontex and Europol exchanging data began back in June of 2022, when the EU’s European Data Protection Supervisor (EDPS), an independent authority, issued negative opinions about Frontex’s data-processing rules. The EDPS subsequently launched an investigation. It did so after analyzing the so-called “debriefing interviews” that Frontex officers, in partnership with national law enforcement, conduct with migrants upon their arrival on European shores. These conversations are in theory voluntary.

During these interviews, migrants are asked questions about the reasons for their journey, or about the possible modi operandi of human trafficking networks. The EDPS report questioned the voluntary nature of these interviews, citing that “the vulnerability of interviewees and the circumstances and manner in which interviews take place means that the voluntary nature of these interviews cannot be properly ensured.” Fran Morenilla – a lawyer specializing in migrant assistance, agrees: “There’s no record of it, because there’s no signed consent form.”

The EDPS also inquired about the use of the information collected. Unlike Europol, Frontex does not have a legal mandate to investigate crimes or to systematically collect personal data to identify criminal suspects. The EDPS criticized Frontex for routinely labeling anyone mentioned during a debriefing interview as a “suspect” and subsequently “transferring” this information to Europol, including “data on persons the interviewee has heard of or seen.” There was no verification about the credibility of the names given, or whether the names were mentioned out of fear, or in an attempt to obtain some benefit.

Under Frontex’s current mandate, in force since 2019, the agency is only authorized to share this data with Europol after a strict “case-by-case” assessment.

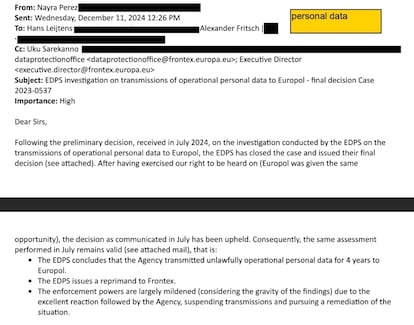

An excerpt from an email sent from the Frontex Data Protection Office (DPO) to Hans Leijtens, the director general of Frontex. It notes that the EDPS has concluded that Frontex “transmitted unlawfully operational personal data for 4 years to Europol” and “issues a reprimand to Frontex.”

An excerpt from an email sent from the Frontex Data Protection Office (DPO) to Hans Leijtens, the director general of Frontex. It notes that the EDPS has concluded that Frontex “transmitted unlawfully operational personal data for 4 years to Europol” and “issues a reprimand to Frontex.”

Following the EDPS’s investigations, an email sent last December by Nayra Pérez – then head of the Frontex Data Protection Office (DPO) to Executive Director Hans Leijtens and his deputy, Uku Särekanno – summarized a clear verdict: “The EDPS concludes that the Agency transmitted unlawfully operational personal data for 4 years to Europol,” Pérez wrote. Indeed, the final investigative report, which focused on the transmission of data between 2019 and mid-2023, confirmed that Frontex “automatically” sent each and every report to its colleagues based in The Hague. Already in 2015, in a previous report, the agency warned that Frontex’s automatic transfers “could constitute a potential breach of the [Frontex] Regulation.”

Frontex suspended this practice just four days after the EDPS’s preliminary report in May of 2023, which included a warning. Since then, it has revised its protocols: now, personal data is only shared with Europol in response to “specific and justified” requests. Of the 18 submitted by May of 2025, Frontex approved only four. “The agency has drawn clear lessons from this experience,” Frontex spokesperson Chris Borowski told this inquiry.

Europol declined to clarify whether it would delete data that was sent irregularly, as required by EU law. Its spokesperson, Jan Op Gen Oorth, maintains that the fact that the EDPS reprimanded Frontex “doesn’t mean that Europol’s data-processing wasn’t compliant [with the law].” Niovi Vavoula, a data protection expert at the University of Luxembourg, emphasizes, however, that the ban on automated transfers is a first step, but “Europol’s responsibility to delete the data it received illegally cannot be forgotten.”

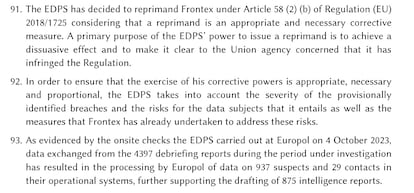

A copy of the EDPS’s final report (dated December of 2024) obtained by this investigation reveals the scale of the data transfers. Between 2020 and 2022, according to Frontex reports, Europol processed the personal data of 937 individuals who were considered to be suspects in human trafficking. Meanwhile, 875 “intelligence reports” were issued, intended for the respective national law enforcement authorities investigating this crime. But this is only a small fraction of the reports on more than 13,000 individuals — including their names, phone numbers and Facebook accounts, among other information that was collected — that the border agency sent to Europol’s European Migrant Smuggling Centre (EMSC) between 2016 and 2023. Maleno was among them. And Olsen and Gruber were suspects too.

Turning people into “suspects”

Frontex claims that it doesn’t collect personal data from interviewees. The agency presents the debriefings of those who share information as being entirely voluntary, but reports from the EDPS and legal experts say otherwise.

Legal experts argue that interviewees lack legal safeguards, such as the presence of a lawyer. The authorities, however, insist that attorneys aren’t necessary, since the migrants aren’t being detained. Daniel Arencibia, a lawyer working on cases involving migrants accused of human trafficking in Spain’s Canary Islands, says that what Frontex does during these interviews “takes place in a black box, in the absence of regular criminal proceedings or legal safeguards that could limit the exposure of vulnerable migrants to criminalization.”

Gabriella Sánchez, a Georgetown University scholar and former criminal investigator specializing in people trafficking, argues that the notion of smuggling used by Frontex and Europol “assumes that all facilitators are organized into networks and is based on racist [perceptions] about smugglers. But, in fact, migrants are systematically accused of facilitating their own smuggling, which accelerates their criminalization. In other words, thousands of people in the EU are caught in the web of data collection.”

One person who was unaware that both Frontex and Europol possess information about him is Tommy Olsen, a 52-year-old Norwegian kindergarten teacher. He has spent years alerting the authorities when people undertaking the dangerous journey from Turkey to Greece are in danger. He has also documented violent pushbacks by the Hellenic Coast Guard. Since 2019, he has faced multiple criminal investigations in Greece: he’s been accused of involvement in migrant smuggling, a charge that he denies.

Tommy Olsen, from the NGO Aegean Boat Report.

Tommy Olsen, from the NGO Aegean Boat Report.

Freedom of Information (FOI) requests submitted to Europol for this investigation reveal that the agency has at least three “intelligence notifications” that mention the Aegean Boat Report, Olsen’s one-person NGO. Europol has refused to disclose the contents, which it considers “highly sensitive” and “relevant to past and ongoing investigations.” In May 2024, a Greek prosecutor on the island of Kos issued a new arrest warrant for the Norwegian activist. Although seven previous police investigations against him have already been closed, he now faces a 20-year prison sentence. “I had no idea Europol had files on me. Why are they collecting and sharing data about my activities and my organization, which simply seeks to defend refugee rights?” Olsen asks.

With more than 800 debriefing officers deployed in its 2024 operations, these interviews constitute, according to the EDPS, Frontex’s “largest operational collection of personal data.”

“It’s extremely difficult to analyze exactly how Frontex exchanges data with other actors, because we lawyers are kept in the dark,” Arencibia emphasizes. Olsen isn’t the only human rights activist who’s been affected. In May of 2022, 35-year-old Austrian activist Natalie Gruber learned of a Europol file on her after submitting a request for access to personal data. The co-founder of Josoor International Solidarity, a non-profit that documents pushbacks from Bulgaria and Greece to Turkey, Gruber became a suspect after the Greek Prosecutor’s Office filed multiple charges against her. She was accused of facilitating the illegal entry of migrants into Greece. One of the open cases was dismissed last year, but the second one remains open.

Natalie Gruber, from the NGO Jasoor.

Natalie Gruber, from the NGO Jasoor.

Citing confidentiality reasons, Europol has refused to release the reports concerning Olsen and Gruber. The agency claims that doing so could “jeopardize [ongoing] criminal investigations.” Gruber has challenged this refusal via the EDPS since 2022, but her complaint still remains unresolved. “You’re faced with this Goliath of bureaucracy that never tells you anything. All you can do is submit another request and wait. It’s exhausting and it profoundly affects your life,” the Austrian citizen laments.

It remains unclear exactly how Europol obtained the information about Gruber and Olsen. Nor is it known whether this information contributed to the criminal cases against them. Olsen’s own request for data, submitted to Europol in April 2025, is pending.

Profound Consequences

The cases of Maleno, Olsen and Gruber represent just a fraction of the thousands of individuals — as well as hundreds of organizations, including humanitarian NGOs — that have landed in Europol databases since Frontex began uploading information to its PeDRA (Processing of Personal Data for Risk Analysis) program in 2016, despite prior warnings from the EDPS.

The EDPS warns of “profound consequences” for those involved; they run “the risk of wrongfully being linked to a criminal activity across the EU, with all of the potential damage for their personal and family life, freedom of movement and occupation that this entails.”

A Persistent Problem

In January of this year, Leijtens formally notified Europol that the information transfers made by his agency up until 2023 were unlawful. According to EDPS chief Wojciech Wiewiórowski, this notification obliges Europol to “assess which personal data are affected by the transmission and proceed with its deletion or restriction.”

Although Frontex was eventually forced to change its protocols, in March 2025, the Fundamental Rights Office (FRO), charged with monitoring Frontex’s implementation of its fundamental rights obligations, alerted the agency’s Management Board about cases in which information from debriefings “was used for the criminal investigation of the interviewed migrants and other persons.” It also expressed concern “about the access and collection of information recorded on migrants’ phones during interviews.”

Reprimand in the final report of the European Data Protection Supervisor (EDPS): “The EDPS has decided to reprimand Frontex pursuant to Article 58(2)(b) of Regulation (EU) 2018/1725 considering that a reprimand is an appropriate and necessary corrective measure. A primary purpose of the EDPS’ power to issue a reprimand is to achieve a dissuasive effect and to make it clear to the Union agency concerned that it has infringed the Regulation,” reads the first point.

Reprimand in the final report of the European Data Protection Supervisor (EDPS): “The EDPS has decided to reprimand Frontex pursuant to Article 58(2)(b) of Regulation (EU) 2018/1725 considering that a reprimand is an appropriate and necessary corrective measure. A primary purpose of the EDPS’ power to issue a reprimand is to achieve a dissuasive effect and to make it clear to the Union agency concerned that it has infringed the Regulation,” reads the first point.

Although Frontex still hasn’t fully implemented all of the EDPS’s recommendations, human rights observers from the agency now have access to some of the interviews. And, last year Leijtens adopted new (albeit non-binding) operational procedures aimed at strengthening safeguards.

But the premise underlying these data collection efforts is flawed, according to academic Gabriella Sánchez: “EU agencies often justify collecting data on migrants by claiming it’s necessary to combat transnational trafficking networks. This creates the illusion that the data is actually reliable or useful. We know this is not the case.”

In 2017, a year after Spain opened a criminal case against Helena Maleno, the Prosecutor’s Office closed the investigation after finding no wrongdoing. However, the case was still passed — without due process — to the Moroccan authorities, who accused her of human trafficking. When she was summoned to testify before a court in Tangier that same year, Maleno was stunned to hear the judge refer directly to the Frontex reports: “I was completely baffled. The judge was specifically asking me about the information contained in the Spanish [National] Police and Frontex documents. It was surreal.”

In 2019, she was acquitted of all charges. But questions remain. “How is it possible that Frontex interrogated migrants about me?” Maleno asks. “Is it really their job to spy on human rights activists?”

An Evasion of Responsibility

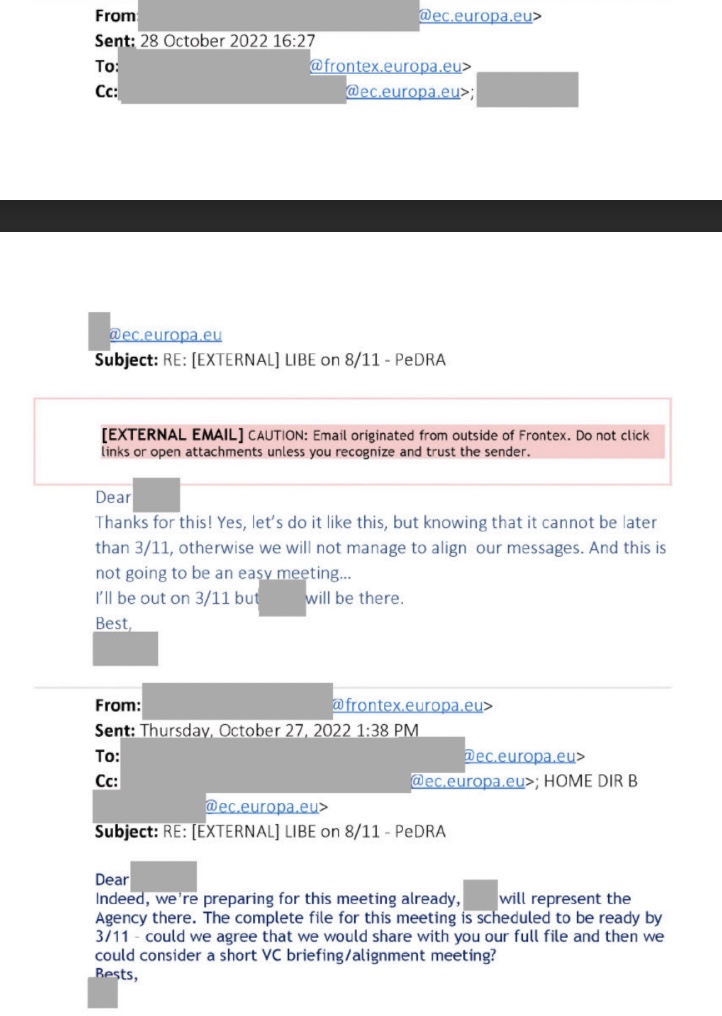

In November of 2022, the European Parliament’s Committee on Civil Liberties held its first hearing on PeDRA, the little-known Frontex surveillance program that transfers personal data to Europol.

Frontex Deputy Executive Director Uku Särekanno explained to MEPs that Frontex had shared data on some 13,000 “potential suspects” with Europol. Särekanno appeared at the hearing alongside two other senior officials closely involved in PeDRA oversight: Jürgen Ebner – deputy director of Europol – and Mathias Oel, then a senior official in the European Commission’s department for Migration and Home Affairs. In synchronized statements, the three officials asserted that the data transfers were exceptional and governed by a robust legal framework.

Särekanno told the Commission: “It’s not a mass transfer of data, but a case-by-case assessment.” Europol’s Ebner echoed this: “We don’t receive bulk data from Frontex; it’s done on a case-by-case basis.” And, according to Oel, transfers of personal data occur solely on an ad hoc basis; PeDRA “isn’t a systematic exchange of data.”

By looking through internal correspondence obtained through a Freedom of Information (FOI) request, this investigation has noted that the three agencies coordinated in advance to “align” their message before speaking with MEPs.

When asked about this, Frontex spokesperson Chris Borowksi affirmed that Särekanno’s statement “was made in good faith and based on the internal understanding and framework in place at the time.” Oel claimed that “the statement was based on information provided by Frontex.” Ebner did not respond.

Luděk Stavinoha is an associate professor at the University of East Anglia, where he researches EU transparency and migration management.

Apostolis Fotiadis is a journalist specializing in EU politics, surveillance policy and digital rights..