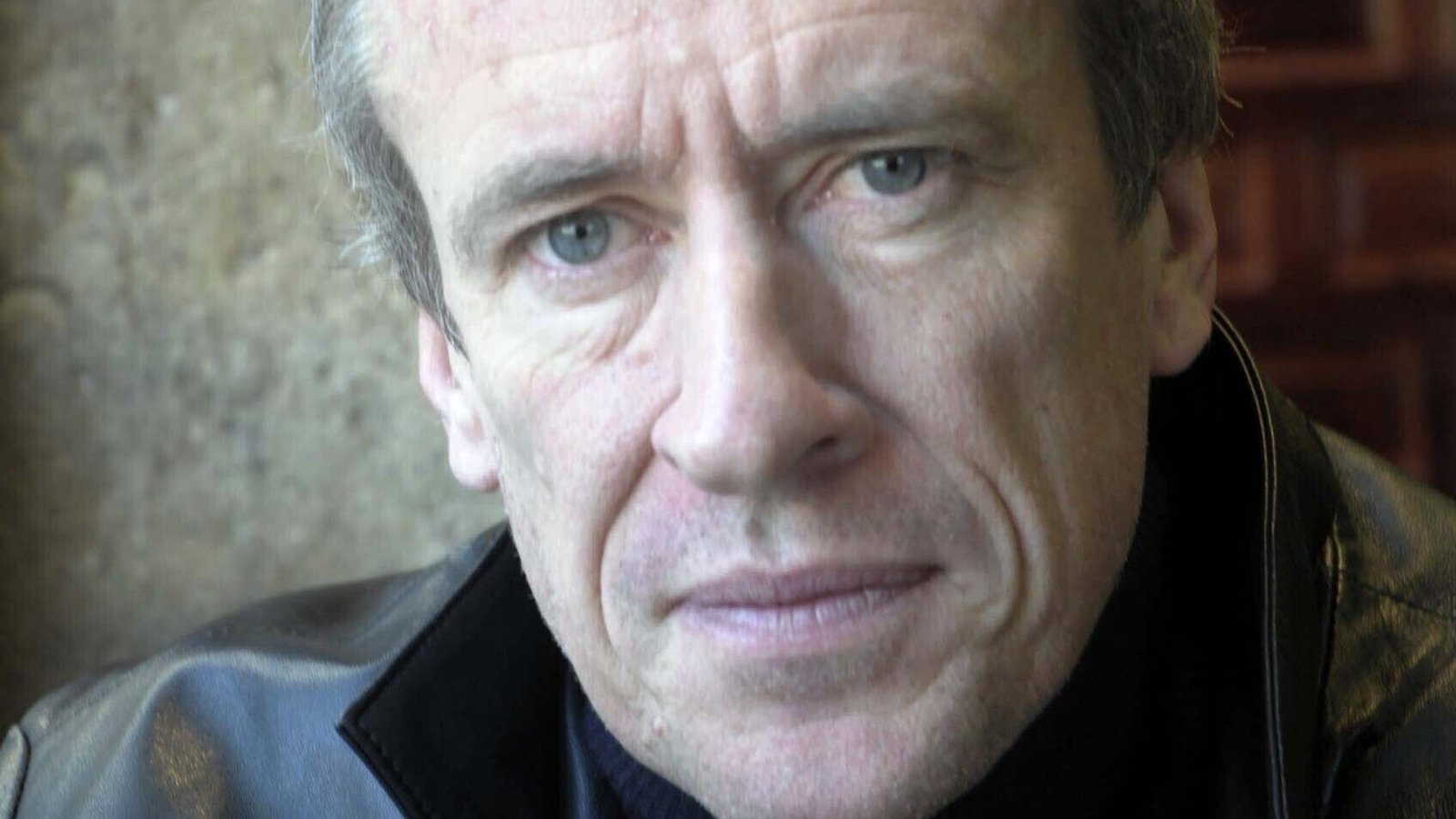

We present an extract from Monaghan, the new novel by Timothy O’Grady, accompanied by illustrations by artist Anthony Lott.

Moving from West Belfast and County Monaghan to the streets of San Francisco, Timothy O’Grady’s exhilarating new novel is an epic portrait of art and war, authenticity and selling out, told through the fates of three men. Ronan Treanor, Monaghan native and teller of this tale, is a celebrated theorist of post-modern architecture in New York. Paul Crane, single son of a hotel maid in Indiana, turns his mathematical gift into a multi-million-dollar career as an investment banker. And the mysterious Ryan, who drew as a boy in besieged West Belfast, but was swept up in the war against the British and lived a decade of extreme and escalating violence as a sniper. Their lives merge and conflict, rise and fall, as one man becomes the undoing of the next.

He and his sister Maire came down from the Hatchet Field and into West Belfast. They went through heather and grass, around hedges and over gates. Around them the smells of silage and tractor diesel, the sounds of birdsong and the light wind. Somewhere they crossed an invisible frontier of sound. There were the distant radios, the calls of children in narrow yards. Behind them in the barracks beside Dermot Hill a landing helicopter caused a gale in the trees and threw up clouds of dust.

They stepped from the path onto the Springfield Road and were again in the tarmac and concrete and brick of the city, resolute, impenetrable, the shadows hard-edged, the low sun catching fragments of broken glass in the wastelands. A foot patrol moved towards them in the silent crouch of formal wariness. One by one the soldiers stopped and tracked them through their telescopic sights.

Somewhere here he told her he wanted to show her a book of the drawings of Auguste Rodin he’d got from the library.

I want you to tell me what you see in them.

OK, she said. Then you’ll take me dancing.

She slid forward on one foot, her whole torso rippling like a flag in a slow wind.

How do you do that? he said.

That’s nothing, she said.

Anthony Lott, Groomsman, mixed media on paper

They turned into the Ballymurphy Road and. He saw Declan White get out of a car. They called him Steeple at school because of his slenderness and height, but they didn’t call him that any more. He’d acquired a look that was no longer suited to a nickname.

What about yez, said Declan.

I’ll be there in a minute, he said to his sister. He watched her move through the shafts of light that came out from between the houses.

Beautiful day, said Declan.

It is. We were up the Black Mountain.

Only trouble is, everywhere you put your eye there’s a Brit.

There’s that.

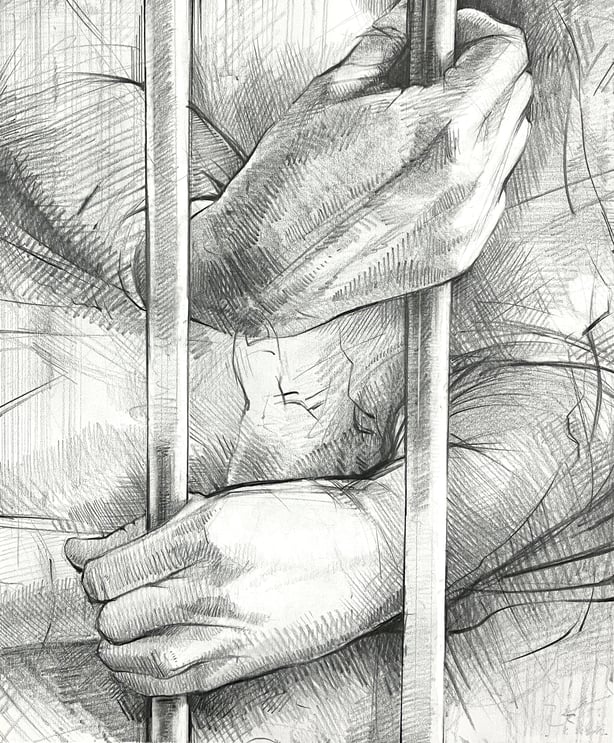

Saw that drawing you did.

What drawing?

Hands on bars.

Anthony Lott, Hands and Bars, graphite on paper

Oh, that.

Yeah. I was in talking to Francie McGuigan. It was up on a wall.

That was just something I did for Ambrose.

How come?

He shrugged his shoulders.

Just, he said.

Here, remember Jimmy Burns? asked Declan.

He thought a minute, but couldn’t find him.

No, he said.

Bones Burns we called him.

Oh aye.

They broke a breeze block over his head.

Who?

Brits.

What for?

What for? Hard to say. Green Howards. Their tour was up. A parting shot, maybe.

How is he?

He’s f**ked. Permanent brain damage. Doesn’t recognise anybody.

He winced at this.

Know what else happened? asked Declan.

Do I have to?

Your call.

All right. Go on.

They killed an eleven-year-old boy in Derry. Shot him in the head with a plastic bullet.

He looked away, took a breath.

What do you think about that? asked Declan.

What can I think? What would anyone think?

Some think, some do.

I know that.

So why don’t you do something?

Everything in him stilled. He raised his eyes slowly to Declan White’s.

What do you mean? he asked.

Anthony Lott, Bridesmaid #5, oil on canvas

Declan tipped his head in the direction of Glenalina Crescent. Come on, he said, and stepped forward. They walked along the pavements, through passageways between houses and back alleys. He understood everything about each place they passed. But after today, he already sensed, it would all look different.

They went over a wall and into a rear garden. An old woman named Magee lived there. He could see her back through the kitchen window as she sat at a table in her housecoat. In a corner on a patch of grass was her dead husband’s pigeon coop, set up on short struts.

They went up the steps, in through a door and crouched in the shadows. Pigeons paced, flapped their wings, cooed. He could see feathers float and twist in the beams of light, the mineral blues and greens in the pigeons’ necks. Declan hauled away sacks of feed from the top of a wooden box and opened the lid. He felt the beating of his own heart as he watched. Inside was a yellow blanket, unravelling a little by the trim. Declan lifted the corners and let it fall open. He saw then what he had been brought there to see – pairs of gloves, binoculars, balaclavas tied together with string, an old, pewter-coloured revolver like from a cowboy movie and two AK-47s. He stood in the shadows amid the murmurs of the pigeons and looked down at the guns.

That’s it, said Declan. That’s what I mean.

I walked to the stream. It was dark here, total blackness amid the bushes and trees. I could sense his presence. Perhaps he could only speak of these things in the dark.

What’s it like to kill someone? I asked.

What makes you think you can ask? he said.

My brother. All that gear on our land.

I heard him shift in the grass. I wondered would he walk away. But he didn’t. Finally he spoke.

I killed Corporal James Nealey of the Staffordshire Regiment on a summer afternoon. I was eighteen, he was twenty-four. He was from a small place called Hixon. His father was a vicar. He was to marry Alice Paulson the following spring. That was the first man I killed. I had a scope and an AR-18. I didn’t always have a scope. It would have been better for me if I hadn’t. I was in an upstairs bedroom window with a clear line on the gate to a barracks. No wind, eight degree drop, three hundred yards. Corporal Nealey was bringing tools to a mechanic who was lying below the undercarriage. I could see him very well. He had red hair and big teeth. It was a clean, simple shot. But I couldn’t do it. My head had decided on the moment but my finger wouldn’t move. He was so near, like I was in a room in his house, like he was about to turn and say something to me. It was so intimate it seemed obscene. I was there to take his life. Something made him laugh. He looked up, towards me. If he could see me as I saw him, our eyes would meet. I’d learned the procedure – check angle, distance, wind, breathe in, hold, pull, move out, dump the weapon, change clothes. I took the breath and pulled. He flew back when the round hit him, his jaw came away. He landed with his arms out. A jet of blood came out of the artery in his neck.

After he killed Corporal Nealey he broke down the gun, got it to a woman waiting with a pram in the back lanes, went over walls and into a house where he washed the evidence off his clothes. Then he sat. That night he watched on the television news his victim’s mother weep, his father pray for peace, his fiancée describe her loss and the police speak of the turning of the wheels of justice which would inevitably arrive to crush him. But he’d known anyway as soon as the round hit that he’d been marked, that all had changed and that he could never go back to who he was.

We talked that night until light came into the valley. I asked him did he wish he hadn’t killed Corporal Nealey.

No, he said. I don’t wish that. But I wish he could have married Alice Paulson.

You can’t have both, I said.

It’s like that, he said.

Monaghan is published by Unbound