A planetary scientist whose discoveries about the moons of Saturn astonished the world has been appointed astronomer royal, becoming the first woman in the role’s 350-year history.

Michele Dougherty has been approved by the King as the first new holder of the post since 1995, taking over on Wednesday from Lord Rees of Ludlow, who is retiring after 30 years.

The role was created by King Charles II in 1675. The role’s original task was to map the heavens to help mariners calculate longitude at sea. Luckily for Dougherty, maritime navigation is not part of the job under the current King.

“My sense of direction sucks,” she said. “My excuse is I was born in the southern hemisphere, so the sun is always in the wrong place.”

Born in South Africa, with English and Irish grandparents, Dougherty, 62, remembers mixing concrete for a base for a ten-inch telescope in the family garden. It had been made from scratch, down to the grinding of the lens, by her father, a civil engineer who later helped her through her physics degree.

She said she was “flabbergasted” when she was nominated for astronomer royal. Until 1972, the holder was also made the director of the Royal Observatory, but since then astronomer royal has been an honorary role, while still part of the royal household.

Dougherty’s expertise lies in designing and operating instruments to measure the magnetic field in space aboard Nasa and European Space Agency (Esa) probes. She made the shock discovery of giant plumes of water spurting like geysers out of Saturn’s icy moon Enceladus during Nasa’s spectacular Cassini mission.

It was in her South Kensington office at Imperial College London, where she has worked since 1991, that she noticed a “tiny anomaly” in the Cassini spacecraft’s measurement of the magnetic field as the probe flew by Enceladus in 2005, suggesting the moon might have an unexpected atmosphere.

Speaking to The Times from her Imperial office, she recalled convincing Nasa chiefs to send Cassini back for a closer look.

“Oh my goodness, I didn’t sleep for the first couple of nights beforehand. Imagine if we hadn’t seen anything. No one would have believed anything I said ever again. But we saw that, instead of an atmosphere, it was a water vapour plume coming out of the south pole.”

Enceladus is now considered one of the most exciting places in the cosmos to look for alien life.

Finding water in liquid form in the frozen depths of the solar system once seemed unthinkable. Now, Dougherty has designed another instrument to find more. The magnetometer is two years into an eight-year journey to Jupiter aboard Esa’s Jupiter Icy Moons Explorer (Juice) mission, of which she is principal investigator.

She is particularly excited for it to scan Ganymede. It is the solar system’s largest moon, bigger even than Mercury, and the only one with a spinning core. The instrument will look for a “global ocean” under the surface.

“If you find liquid water, it’s one of the ingredients you need for life to form,” she said, comparing it to looking for “needles in a haystack, but the needles change shape and colour all the time”.

Dougherty began work on Cassini in 1992. It operated until 2017, 25 years later. She started on Juice in 2008. It will reach Jupiter in 2031 and operate until 2035. Might she work on further missions, perhaps to Uranus?

“Hell no,” she said. “It takes 30 years for these things to happen. In 20 years, I plan to be sitting in the sunshine drinking wine. I like drinking wine now. As you can see, there is a wine fridge in the corner.”

It is used to coax academic colleagues into her office for an end-of-day drink, she explained, though she thought it wisest not to bring one to the Science and Technology Facilities Council (STFC).

Dougherty in her office in South Kensington, where she tempts colleagues with the offer of a glass of wine

JACK TAYLOR FOR THE TIMES

She was made chief of the body, which funds university researchers, in January, 15 years after writing a furious letter to The Times blasting the STFC for making “horrible’ cuts to funding for UK researchers working on Cassini. She warned, however, that science funding would “have some difficult financial times ahead”.

Dougherty is a fellow of the Royal Society, which held crunch talks over whether to expel Elon Musk over threats to scientific research while he was part of President Trump’s administration.

“I wasn’t involved in those meetings,” she said. “My understanding is the reason he wasn’t [expelled] is that he was elected for what he had achieved. And what he achieved in enabling easier launches into space has not gone away.

“Things are unsettled right now across the world on a range of fronts. That’s why it’s so important that in the UK we are very open about why we do the research we do and why it is so important to the health and wellbeing of the UK economy.”

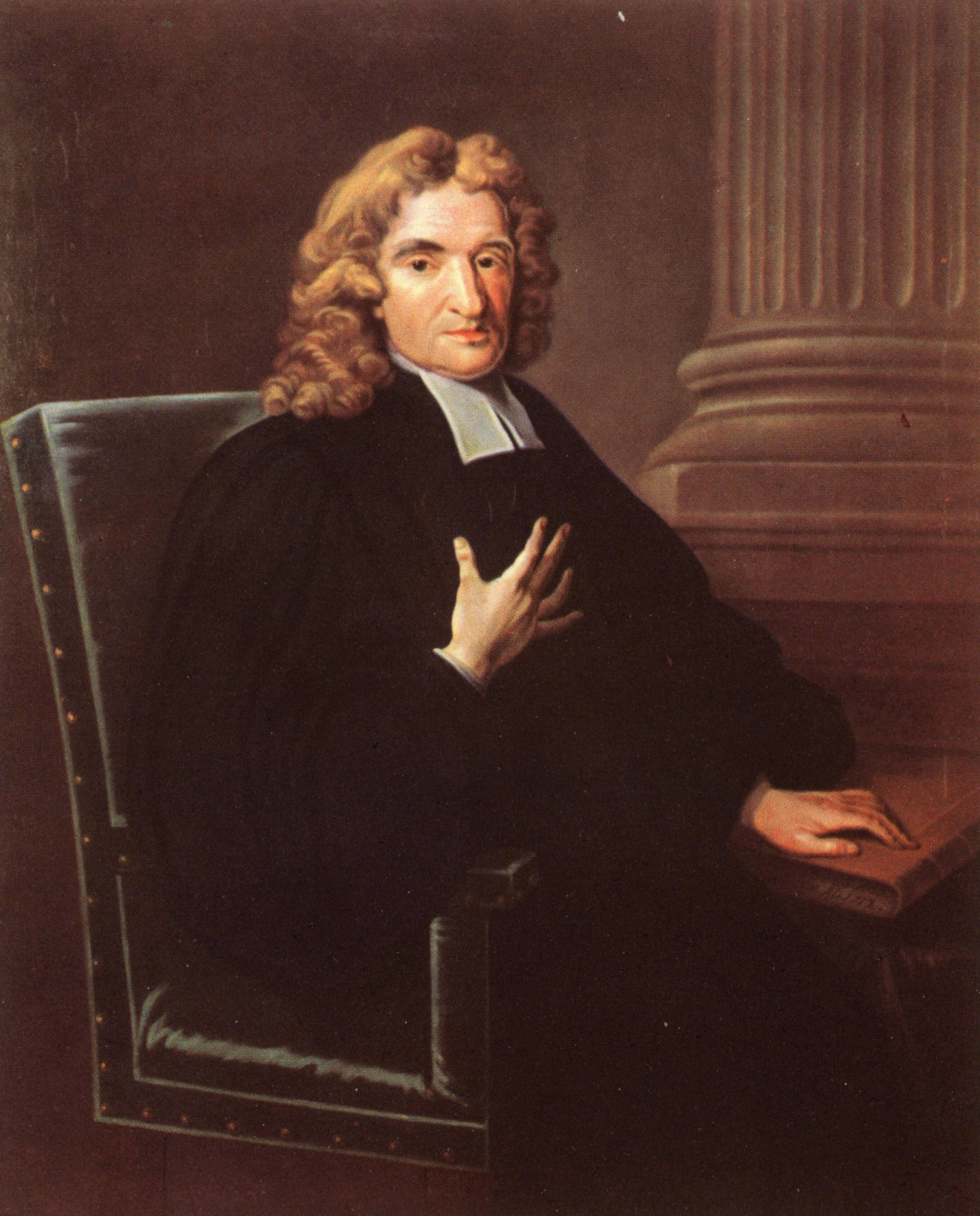

The first astronomer royal was John Flamsteed, followed by Edmond Halley, after whom a comet is named.

John Flamsteed, painted by Thomas Gibson in 1712

ALAMY

Thirteen more men followed up to Rees, 83, who said this week that Dougherty’s work is “very exciting” and that he hoped she could be a “strong, independent voice for science”.

Dougherty said: “Being the first woman is confirmation of how far we have come. [But] I don’t want to be the first woman to do something because I am a woman, but because of what I’ve done to put me in that position.”

Her main role as astronomer royal will be to “talk to people about the science we do and how it can impact people,” she said. “And also just to make them excited. Isn’t it nice to get excited about things? I want to enthuse and excite people.”