The first impression you get of Penrhyn Castle is of a typical National Trust property where visitors can stroll in the gardens, take their children to the play area, enjoy a cream tea in the cafe or even buy a second-hand book in the stable block.

But this image of a fun family day out is in stark contrast to the castle’s divisive history. Not only was the property built on the profits of the slave trade in the early 19th century, but it was also at the centre of the longest-running industrial dispute in British history.

The Great Penrhyn slate quarry strike, which ran from 1900 to 1903, was a culmination of several years of dissatisfaction and unrest in the quarrying industry. The Welsh slate industry employed about 17,000 workers in the 1890s and produced almost 500,000 tonnes of slate a year, around a third of all roofing slate used in the world.

The dispute, which was sometimes violent, centred on union rights, pay and working conditions. This bitter battle between Lord Penrhyn and the slate quarry workers ripped apart the community and changed this part of north Wales forever.

A slate-splitting demonstration at the museum National Museums Wales – Llanberis Slate Museum

A slate-splitting demonstration at the museum National Museums Wales – Llanberis Slate Museum

The long and complex history of the industry in north Wales will soon be retold at the Amgueddfa Lechi Cymru – National Slate Museum in nearby Llanberis, which is undergoing a £21m redevelopment. The museum is part of Amgueddfa Cymru – Museum Wales, which runs six other national museums and a collections centre.

The National Slate Museum closed in November 2024 and is working closely with local communities to shape the project. Outreach work includes demonstrations of slate splitting at Penrhyn Castle. The project has included the creation of a temporary off-site collections store, which offers public tours.

When the museum reopens in 2026, it will join another national museum being created in north Wales – the National Football Museum, which is being developed by Wrexham Council alongside Wrexham Museum, which is also getting a makeover (see below).

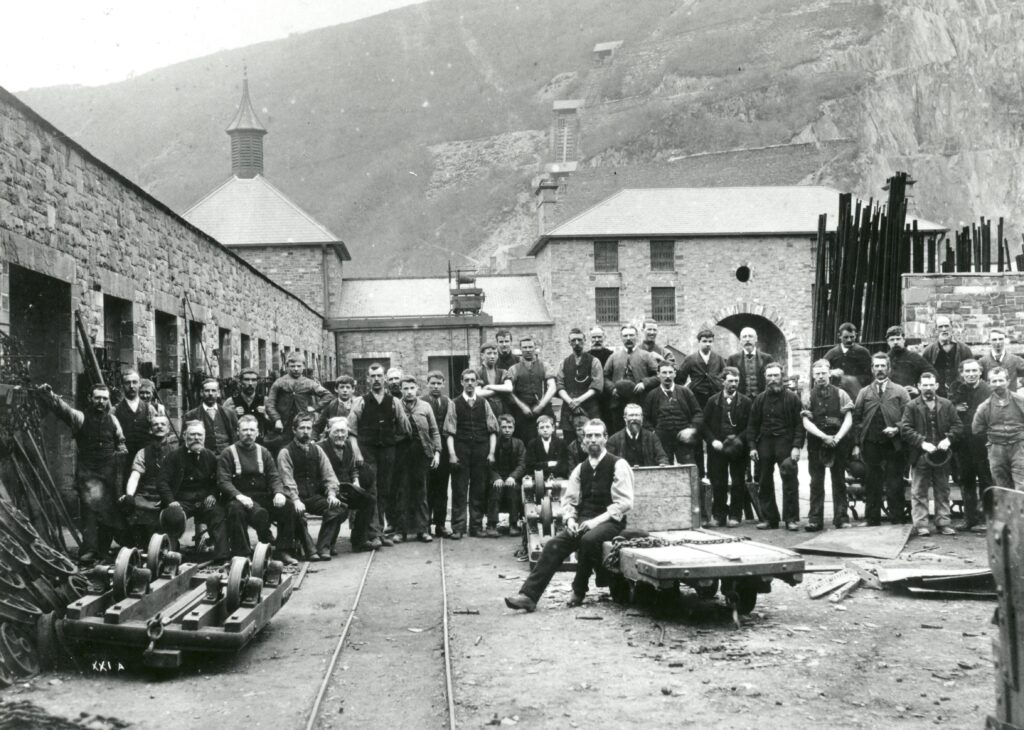

An archive photo of workshop staff at Llanberis Slate Mine in 1880 National Museums Wales – Llanberis Slate Museum

An archive photo of workshop staff at Llanberis Slate Mine in 1880 National Museums Wales – Llanberis Slate Museum

The global importance of the slate industry was given official recognition in 2021 when the landscape was designated a Unesco World Heritage Site. This status gave a huge boost to Amgueddfa Cymru’s plan to redevelop the museum.

“The award was one of the key levers that brought in some of our funding,” says Helen Goddard, the project director for the National Slate Museum redevelopment. “And with the museum, we are positioning ourselves as a gateway to the wider World Heritage Site.”

As well as its global importance, the slate industry had a huge impact on Wales itself, not only economically, but culturally.

Slate production was essentially a Welsh-speaking industry, as most of the workforce was drawn from the local area. Partly as a result of this, north Wales is and continues to be a place where there are high number of Welsh speakers. The slate industry also influenced Welsh literature and music and, of course, politics.

The National Slate Museum is at the foot of what was one of the largest slate quarries in the world, Dinorwig Quarry. It is housed in the original engineering workshops, built in 1870, which once employed more than 3,000 workers. The quarry closed in 1969 before reopening as a museum in 1972. It was redeveloped in 1999.

The Unesco designation has given Amgueddfa Cymru what it describes as a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to invest heavily in the site and transform the visitor experience.

“This is a hugely significant project for us as an organisation, and the whole of Amgueddfa Cymru is very much behind it,” Goddard says.

The quarry closed in 1969 before reopening as a museum in 1972 National Museums Wales – Llanberis Slate Museum

The quarry closed in 1969 before reopening as a museum in 1972 National Museums Wales – Llanberis Slate Museum

“It fits with the renewed vision that we’ve got around being a truly national organisation with a truly national reach. The position we’re in gives us the opportunity to share more of the national collection.

“We strongly believe that people shouldn’t have to travel to Cardiff if they want to experience some of our collections. So, we are taking that chance here and will be bringing in collections that people would normally have to travel to the south to see.”

The redevelopment includes a new temporary exhibition space, which will provide opportunities to work with local communities on developing exhibitions.

“We’re really excited to use that space, as it will be a launchpad for co-designing with communities,” Goddard says. “We will be looking at how we might work together to have a slightly more equal relationship in terms of the power dynamic of selecting the objects that are going to go on display.

It will be about going into collection stores, selecting objects, handling them and discussing them, and asking whether an object is appropriate for display and what are the stories that you can tell with it? It’s a fertile thread that runs through the vision for the project as a whole and we are especially excited about it.”

The revamped National Slate Museum will have to cater for a wide range of visitors – from local communities with a deep connection to the slate industry to international tourists who come with little prior knowledge of slate mining.

“Some visitors may wander in and not know anything at all about the story of the site,” Goddard says. “So, it’s finding ways to make sure that we are using those universal themes and the wider global story to bring it to life for people.”

All visitors, wherever they are from, are likely to be attracted by the hands-on demonstrations that were already a big draw before the museum closed for redevelopment. Communicating activities that fall under the banner of intangible cultural heritage are a crucial part of Unesco’s World Heritage designation and provide a fantastic visitor experience.

“This is the only place really in the world where you’ll see slate splitting in the way that we show it,” says Elen Roberts, the head of the National Slate Museum. “It’s a huge unique selling point for us and it’s something that we want to celebrate as part of the redevelopment. It is what keeps people coming back as well, because they won’t see it anywhere else.”

The great strike of 1900-03 marked the beginning of the decline of the Welsh slate industry. World war one saw a big reduction in the number of men employed in the industry, while the great depression and world war two led to the closure of many smaller quarries. Finally, competition from other roofing materials led to the closure of most of the larger quarries in the 1960s and 1970s.

But although Welsh slate production is nowhere near the size it once was and employs far fewer people, it is not just a museum piece. Welsh slate, which is very high quality, continues to be used for roofing and a range of other applications, including landscaping, kitchen worktops, fire surrounds and bathroom tiles.

But a visit to the National Slate Museum next year when the redevelopment is complete will be the best way to understand the huge impact that the industry has had on Wales and the rest of the world.

A museum of two halves

John Charles debut shirt for Wales v Ireland 1950 Wrexham Museum

John Charles debut shirt for Wales v Ireland 1950 Wrexham Museum

How a new national football museum is being developed alongside an upgraded Wrexham Museum

Even before two Hollywood stars invested in the town’s “soccer” club, Wrexham was seen as the home of Welsh football.

But there is no doubt that actors Ryan Reynolds and Rob McElhenney, the co-owners of Wrexham Association Football Club since 2021, have had a huge impact on the area. Wrexham AFC have just been promoted to the English Football League Championship, their third promotion in a row, with their recent progress documented in the television series Welcome to Wrexham.

But there is another important football story happening in the town – the development of Wales’s first football museum, which is being created alongside an enhanced and expanded Wrexham Museum.

In fact, this project was underway before Reynolds and McElhenney bought the football club.

Both the National Football Museum and Wrexham Museum will be run by the museum team at Wrexham Council. The exhibition designer for the project is Haley Sharpe Design, the architect is Purcell and

SWG Construction is the main contractor.

A visualisation of the exhibition Haley Sharpe Design

A visualisation of the exhibition Haley Sharpe Design

Funding has come from Wrexham Council, the Welsh Government, National Lottery Heritage Fund, the UK Government (through the UK Shared Prosperity Fund) and the Wolfson Foundation.

The working title for the project is the Museum of Two Halves. The site was built in 1857 as a barracks for the Denbighshire Militia, becoming the home of Wrexham Museum in 1996.

Wrexham is the birthplace of the Football Association of Wales, and Wrexham Museum is the custodian of the official Welsh Football Collection, which has thousands of items from Welsh football history.

When it opens next year, the football museum will be the first national museum in Wales not operated by Amgueddfa Cymru – Museum Wales.

About 30,000 people used to visit the former Wrexham Museum each year, but the council is hoping that the two museums together will attract at least 85,000 in its first year.

“It is quite a big jump, but it’s a much bigger offer,” says Karen Murdoch, the interim museum manager at Wrexham County Borough Museum & Archives.

We are always talking to people to make sure we’ve got that representation of all the clubs across Wales

Karen Murdoch, the interim museum manager at Wrexham County Borough Museum & Archives

“We’re hoping for that national pull for the football museum and that the people who come for the football might come and learn a little bit about Wrexham, and the other way around. It should work quite well.”

Murdoch says the high profile that Wrexham AFC has gained is helping to attract visitors to the area from far and wide, including the US and Canada, but there is no formal partnership between the football club and the museum service.

“They’re very protective of their brand and have everyone knocking on their door and wanting to work with them,” Murdoch says. “It’s an interesting relationship and it might take the museum to be open for things to happen.”

Murdoch also says it is important that the displays in the museum tell a national story, with two football engagement officers helping to make this happen through their work gathering collections and stories from across Wales.

“We have to be careful in terms of our offer and make it clear that we’re a football museum for all of Wales, not just Wrexham,” Murdoch says.

“We are always talking to people to make sure we’ve got that representation of all the clubs across Wales, and at all levels.”

Enjoy this article?

Most Museums Journal content is only available to members. Join the MA to get full access to the latest thinking and trends from across the sector, case studies and best practice advice.