Photograph by Suki Dhanda

A baby boy is discovered naked next to a rubbish bin near a monastery in South Dakota. The monks raise the child; by the time he is five years old, three of them are raping him. On his eighth birthday, one monk goes on the run with the boy, hiring him out to groups of men in motels between Texas and Montana. By the age of 14, he is in a children’s home, being beaten with a vinegar-soaked belt and made to eat vomit. The boy manages to flee 2,000 miles east in the direction of Boston by offering sex to passing drivers, one of whom imprisons him for 12 weeks, making him “do things … he was never able to talk about”.

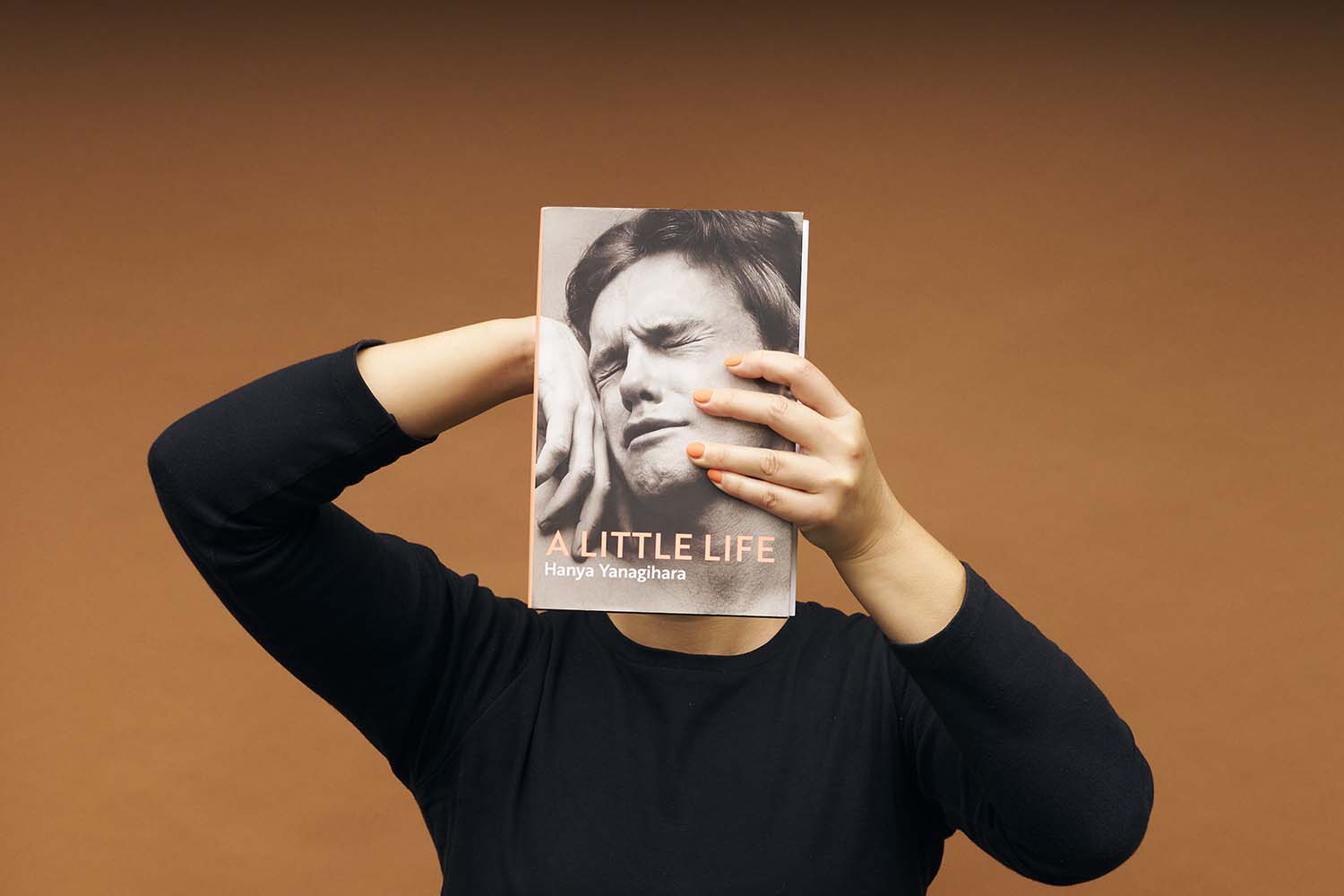

This, as millions of readers around the world know, is only a sliver of the nightmarish childhood of Jude St Francis, the high-flying lawyer at the centre of the Booker-shortlisted blockbuster A Little Life, published by the American writer Hanya Yanagihara in 2015. A decade on, sales continue to accelerate steadily, buoyed by a consistently surprising breadth of endorsement.

The UK foreign secretary, David Lammy, said in Politico that it was the best book he read last year. The designer Victoria Beckham enthused to Elle about reading it on her Kindle in bed every night in 2017. TV presenter Naga Munchetty gives friends copies “because they need to read it”. “What reading A Little Life taught me about leadership” ran a recent headline in the business magazine Forbes.

In 2022, when a man named Bob Jackson read every novel ever nominated for the Booker prize – 315 titles going back more than 50 years – his favourite wasn’t Wolf Hall or The Line of Beauty but A Little Life: “I keep running it over in my head, asking if there’s anything better. But I don’t ever come up with anything that has generated such lasting fondness.”

Nobody saw the success coming. Yanagihara, editor-in-chief of T, the New York Times style magazine, hoped for “a few dozen readers” for her book. By 2021, 245,000 print copies had been sold in the UK; the figure now stands at about 550,000, excluding digital copies and audiobooks (a new recording by Magic Mike’s Matt Bomer came out in February).

“I wouldn’t have judged it to be a book that should have wide appeal,” said James Daunt, the managing director of Waterstones, blindsided by early demand for a 730-page litany of degradation that Yanagihara’s own editor reckoned would be “just too hard for anybody to take” (he wanted it cut by a third; Yanagihara said she’d go elsewhere if he didn’t take it as it was).

Even the book’s admirers – I’m one – are left in two minds. One review declared: “A Little Life is the best novel of the year. I wouldn’t recommend it to anyone.” Online, there are tearful TikTok reviews and Instagram selfies of fans tattooed with their favourite lines but also outraged Reddit and Mumsnet threads condemning it as misery porn – a charge levelled repeatedly in reviews for A Little Life, many of which are scathing.

That particular criticism still doesn’t convince me, but if I felt sure of one thing when I reviewed A Little Life positively back in 2015, it’s that I wouldn’t be reading the novel again any time soon. Even the title makes me recoil. Deep into the book, those three words turn radioactively evil: “a little life” is what eight-year-old Jude’s first kidnapper says he needs to show, to please the men paying to rape him.

It’s the moment I think of whenever I see the novel mentioned. Yanagihara lulls us into interpreting the title – an echo of a line in TS Eliot’s The Waste Land – as merely condescending or ironic before demonically electrifying it, 400 pages in. Much of the book was written late at night in the renovated bottle factory in New York where she lives (the steel beams apparently block internet reception); I’ve never been able to shake the thought of her calculating that ugly twist after dark.

Author Hanya Yanagihara resisted editorial pressure to shorten the novel

For me, the passage is enough by itself to torpedo the widespread notion that A Little Life is badly written, yet I still struggle to make sense of the book’s astonishing popularity. Just reward for a modern classic? Evidence of our cheap taste for trauma? A symptom of post-millennial malaise? As I spoke to some of A Little Life’s fans and haters, and readers in between, trying to understand why the novel speaks so strongly to us and what it has to say, I heard all these arguments and more – wondering all the while if I was only putting off the moment when I’d need to reimmerse myself in its universe.

The novelist Megan Nolan was 25 when A Little Life came out. She read it at the time and says there’s no mystery about the book’s success. “It’s like a car crash: Yanagihara is very skilled at creating grotesque moments of extremity that you can’t look away from and manages to repeat that all the way throughout.” Nolan was gripped but suspicious of the novel’s melodrama until she recently listened to the audiobook when it popped up on her Spotify account. “I was taken aback by how absolutely strange it is – I don’t actually know if I like it or not, but I respect how bizarre it is,” she says.

Part of that peculiarity – ignored by those who focus solely on the trauma – lies in the extreme sense of whiplash generated by the contrast between Jude’s past and his gilded adulthood, where the book begins. Yanagihara, who wanted everything in the novel “turned up a little too high”, like a fairytale, shrouds Jude’s grisly history deep inside a glossy narrative of his life together with three former college roommates, who each match his stellar law career with their own outstanding achievements in art, acting and architecture.

Throughout the book, the four crisscross the globe (there are trips to Paris, Rome, Doha, Tokyo, Hanoi, Morocco and Ethiopia, among a dozen or so other destinations), enjoying any number of sedulously enumerated dishes – guava soufflé, sablefish with tobiko – and at one point sourcing marble for a kitchen countertop from “a small quarry outside Izmir”. Jude calls in a favour from Spain’s minister of culture to close down the Alhambra for a private birthday tour. His increasingly complex medical problems – including a degenerative spinal condition and sepsis from chronic self-harm – are tended to 24/7 by his close friend, Andy, a Welsh-Gujarati orthopaedic surgeon, whose wife says his devotion to Jude is what first attracted her to him.

These elements, improbable as they might sound, are key to the case that A Little Life makes for the importance of friendship and a large part of the novel’s appeal to its fans. (When one character suggests that Jude and co should “stop clinging to one another and get serious about adulthood”, the reply comes: “Thousands of years of evolutionary and social development and this is our only choice?”) Yet the near-utopian camaraderie of the main characters – all dead by middle age – ultimately makes the novel all the more devastating.

Hearing about me writing this piece, a colleague puts me in touch with her daughter, Caitlin Duffield, who read the novel during lockdown on the recommendation of a friend while furloughed from her job at a mental health charity. “He didn’t warn me – he just said: ‘It’s excellent and really sad, read it.’” She took to her mum’s sofa for a week, overwhelmed. “I remember just weeping constantly, even at the happy moments,” she recalls. Afterwards, she looked up drawings posted by fans online, wondering who might play the characters on screen. “I just wanted to stay with them, which is something I don’t tend to feel [after a novel].”

But Duffield, 25 at the time, felt differently after passing it on to another friend in turn. “He messaged me later: ‘What the hell are you doing recommending me this book? It’s horrible. Why did you like it?’ I started to interrogate the extent of the suffering and almost felt embarrassed. Looking back, it becomes so depraved. But at the time I was captivated and totally invested.”

The writer and broadcaster Pandora Sykes, 38, had similar misgivings. She got a copy when it came out and took it to a wedding in France, which was “absolute agony – all I could think about was how soon I could get back to the book. It seemed to be proving a basic, almost biblical truth that sometimes the world is desperately cruel again and again to the same person: having a terrible experience in life doesn’t inure you from having another.”

But as the years went on, Sykes questioned how far she had been drawn to what she calls the “trauma porn” element, buying tickets nonetheless for the keenly anticipated West End stage adaptation in 2023 (Jude was played by Happy Valley’s James Norton). The audience walkouts made headlines, but Sykes didn’t get that far, selling her seats: “I’d just had a baby and I thought: ‘Do I really need to be putting myself through this?’”

Looking back, it becomes so depraved. But at the time I was captivated and totally invested

For Uli Lenart, the manager of Gay’s the Word bookshop in Bloomsbury, central London, A Little Life is totemic: if it were ever to be out of stock from his shelves, he would feel that something was deeply amiss. “It’s an intense experience. It’s not just reading a book. I often advise [customers] a degree of self-care during the period where they read it.” He attributes the novel’s ability to connect with readers partly to the fact that “some people’s lives are a marathon of horrific experience”, but also to its indefinable tone and oddly ethereal setting over a 50-year span in New York, untouched by 9/11; Aids is mentioned only once, in passing. “The narrative, existing in a kind of temporal bubble, enables us to explore our own experience of taboo subjects that society alludes to but doesn’t really delve into,” says Lenart, 46.

It’s easy to forget how timid and exhausted Anglo-American fiction seemed when A Little Life first came out. David Shields’s 2010 manifesto Reality Hunger set the mood for a decade in which authorial imagination was suspect if it didn’t visibly wear the lanyard of experience. Rachel Cusk said making up stories was embarrassing. The hot authors of the day – Sheila Heti, Ben Lerner – wrote about themselves, often in mundane and minute detail. Nothing spoke more starkly of the seeming loss of creative confidence than an interview in which Jonathan Franzen claimed that he had considered adopting an Iraqi orphan to write about young people with more insight.

Enter Yanagihara. Born in Los Angeles in 1974, the daughter of a Hawaiian oncologist of Japanese descent, she first worked in publishing, acquiring the US rights to Sarah Waters’s novel Tipping the Velvet, before switching to journalism during the dotcom boom. All the while, she was at work on her 2013 debut, The People in the Trees, written over 18 years. It sold poorly, but Yanagihara has spoken of the creative freedom that comes from not trying to make a living from fiction: working as editor-at-large of Condé Nast Traveller gave her the security to refuse the cuts that A Little Life’s editor advised.

Her poise was unusual; when asked by interviewers how she felt able to write about gay men and about such delicate subjects, she responded that she could write about whatever she liked. She didn’t research Jude’s storyline and claimed almost trollishly that his sections always came easiest during the 18 months A Little Life took to write.

At a time when novels were getting shorter, bittier, as if even to put one sentence in front of another was passé, Yanagihara instead produced a 375,000-word saga that compelled you to care about its characters. The page-turning quality – the comedian Nish Kumar called it “the most immersive novel I’ve ever read” – has much to do with the guessing-game structure of the first 300 pages, during which Jude repeatedly cuts himself in private.

His friends see that he needs help but, like us, they don’t know why, accepting his silences and vagueness when asked about his childhood or why he always wears long sleeves, even in the sea. Then the novel plunges suddenly into Jude’s boyhood at the monastery, opening a wave of revelations that intensify in horror.

Daniel Mendelsohn, 65, was one of A Little Life’s most disparaging early critics. Writing in the New York Review of Books, he called the prose ungainly and the storyline gratuitous, “neither just from a human point of view nor necessary from an artistic one”. Baffled by its praise, he cited a Psychology Today article on “declining student resilience” and hypothesised that, “when victimhood has become a claim to status”, millennial readers accustomed to “helplessness and acute anxiety” might be finding solace in a novel that confirms “their pre-existing view of the world as a site of victimisation and little else”.

When I asked him recently if he’d changed his mind, he told me he continues to be shocked by A Little Life’s success but that he now views it merely as a symptom of general dumbing down. “I think this is a subject that’s larger than just A Little Life. The sentences are so terrible. I couldn’t believe that serious people – people I know – were saying this is so great. There’s something un-adult about this thing that’s happening, where adults are satisfied with a young-adult level of gratification. With a lot of novels that have become great literary occasions, I think: ‘You’ve got to be kidding me, this is teenage literature, basically.’”

Singer Dua Lipa’s praise of A Little Life on social media led to a ‘directly attributable’ sales bump

When the novel was shortlisted for the Booker prize in 2015, the judges were the late poet John Burnside, the biographer Frances Osborne, the publisher Ellah Wakatama and the critics Michael Wood and Sam Leith. “Not the Instagram generation,” says Leith, who was 41 at the time. “I was probably the youngest, and I’m an old fart.” He says the jury knew you could make a long list of what’s wrong with A Little Life, but that would have been to ignore its power. “It’s one-note, but that note is sustained so wine glasses are shattering in the room next door. It was definitely one of the most baffling books in terms of accounting for its success, but our job as judges was just to recognise when something works, rather than necessarily being able to explain why.”

Wakatama, 58, tells me A Little Life has been on her mind ever since judging the prize, when she read all 700-plus pages in a sleeplessly rapt 28 hours while on holiday in Turkey. “How relentless can you be? How much can you mess around with your reader’s emotions? [Yanagihara] goes to the edge and over. You’re then forever trying to figure out why she did it that way. That’s great literature.”

Once I finally returned to A Little Life during the humid nights of a recent heatwave, I realised I’d forgotten the stark contrast between the flatly shocking details of abuse (which are implicit but not graphic: Yanagihara knows it’s enough to tell us the men in Jude’s motel rooms bring their own bedsheets) and the worryingly lush descriptions of self-harm (when Jude opens a vein, his blood is a “brilliant, shimmering oil black”).

What I don’t think I’d ever noticed was how far the atmosphere of gothic terror cloaks a subversive novel of ideas, in which the pile-up of atrocities serves as an intellectual bedrock for provocatively rationalised renunciations – of sex, of life – that, if anything, left me feeling even more uneasy than I was 10 years ago.

It strikes me now that the much-discussed lack of substantial female characters in A Little Life functions as a way to eliminate the possibility of pregnancy from a fictional world in which every child is a tragedy in waiting. Besides Jude, who is abandoned, a vessel for criminal appetite, the novel shows us two other children (relatives of supporting characters); one dies after suffering cerebral palsy, the other dies of a rare neurogenerative disorder. As one character observes: “If we were all so specifically, vividly aware of what might go horribly wrong, we would none of us have children at all,” a line that Yanagihara might have had pinned above her desk. Jude, suicidal, ends the novel concluding that, despite all his achievements, he was “most valuable in those motel rooms”, one of the more gut-plummeting lines in a book that offers plenty by way of competition.

Nothing is revealed about Jude’s biological parents, not simply because it’s beyond the book’s scope, but because we’re constantly nudged to view him as a self-birthed evolutionary breakthrough purged of bodily wants. Avoiding sex in adulthood, Jude wonders if he is missing out an “essential part of being human”, but the answer given by the novel, repeatedly, is no.

Venturing reluctantly on a date with a fashion designer, he falls prey to yet more terrifying abuse; later, when his friend Willem convinces him that their platonic love is actually romantic, he agonises over the duty he feels in bed. A simpler, sunnier novel might have allowed Jude to rediscover his stolen capacity for desire; instead, his dilemma – sensitively portrayed – lets Yanagihara interrogate the necessity of sex in the first place. “When did you get to stop wanting to have sex?” Jude thinks. “Surely his hatred for the act was not a deficiency to be corrected but a simple matter of preference?”

A good deal of the novel’s emotional impact lies in its portrayal of this renunciation as choice, not trauma. In interviews, Yanagihara has said that she never wanted a family, contrasting her lack of belief in marriage with her faith in cherished loyalty to close friends who feel similarly: “This sort of life never seemed like anything ‘less-than’ to me. The loneliness of living the life I do comes from the fact that so many people do think it’s a lesser existence, a purgatory of true adulthood.”

Given that A Little Life goes to great lengths to portray Jude as an advanced human – his scarred back is “something otherworldly and futuristic, a prototype of what flesh might look like 10,000 years from now” – you wonder: does Jude suffer so much because Yanagihara simply wanted the most compelling repudiation possible of the social pressure to pair off into child-rearing couples?

Ravi Mirchandani, A Little Life’s UK editor, recently spoke of owing several of his end-of-year bonuses to the pop star Dua Lipa, who tweeted to her then five million followers a selfie recommending the book while sunbathing in May 2020 in lockdown (the sales bump, he said, was “directly attributable”, and repeated when the singer interviewed Yanagihara on her At Your Service podcast two years later). Lipa, 24 at the time of the tweet, has since called the novel “a homage to the purity of friendship above all”, and you can see how its idealised portrait of group loyalty might have been catnip to gen Z readers starved of real-life contact during the pandemic.

It’s not hard to imagine that the darker side speaks to them too. Although you can find an anonymous blogger arguing online that A Little Life is popular with gen Z because “it’s an icky fantasy about being the most special victim on the planet ever” – a cruder update of Mendelsohn’s take – I suspect the truth is more complicated.

We’ve all seen the headlines about falling birth rates and how young people aren’t having sex, whether because they’re too busy respecting boundaries, scrolling their phones, rethinking coupled-up normativity or daunted by rising costs and temperatures. Whatever the reality, if A Little Life speaks to a cohort coming of age in a post-crash, post-pandemic, pre-AI world upturning old certainties about education, work, sex and relationships, can we really be surprised?

Yet what strikes me most, second time round, is the novel’s weirdly clairvoyant prefiguring of a reading experience that has become so central to everyday life for so many of us, boomer or zoomer. You couldn’t sensibly call A Little Life a novel about the internet – it barely features – yet reading it now, it feels so clearly of the internet age. The ever-updating departure board of exotic destinations, the semi-infinite tasting menu of tempting dishes, the artfully curated interiors, all mingled with retina-scalding scenes of violence and suffering: how different is this from the experience of the average half hour on social media, where raw footage from warzones sits beside paid content from vloggers flying first-class to luxury hotels?

If the TikTok generation gets it, no wonder: Yanagihara might have dared hope for only a few dozen readers, but the world soon caught up with her vision.

A 10th anniversary collector’s edition of A Little Life by Hanya Yanagihara is published by Picador on 2 October (£25). A celebratory event, Hanya Yanagihara: A Little Life at 10, will be held at London’s Southbank Centre at 8pm on 8 October.

Photographs by Siân Davey for The Observer/@dualipa