Some say Shanghai began as a crab fishermen’s market; others claim its first inhabitants came from southern China, fleeing the Mongols. They settled at the old port, where centuries later they built walls to fend off Japanese pirates — walls that, in 1842, did not withstand British cannons. The British consul chose the junction of two Yangtze tributaries to set up his embassy and control the river. For some, that moment marked the city’s true beginning. Others disagree, believing the real Shanghai — the one of glass towers and colorful lights — was born in 1992, when the Chinese government launched the construction of the financial district west of the river.

The truth is that few cities have transformed so much and so quickly. From a village of peasants to a colonial enclave, from a revolutionary stronghold to a global port with the third-largest urban GDP in the world, Shanghai has always been at the forefront. Even long before the skyscrapers and high-speed trains, it attracted adventurers and exiles. A refuge for Tsarist Russians, Baghdadi bankers, revolutionary thinkers, and opium smugglers, the Chinese metropolis brought together the most cosmopolitan population in Asia during the first half of the 20th century, eventually becoming a haven for Spaniards as well.

Between the Chinese characters and steamed baos, its streets still offer a glimpse into the most unlikely history: Spanish Shanghai. A neo-Mudéjar mansion, luxury cinemas, ballrooms, and the remains of a Basque pelota court hide the hallmarks of a small community that nonetheless left a lasting mark.

Antonio Ramos’ cinema

In 1865, the first census of foreigners recorded 131 Spaniards — all men. Most were concentrated in the so-called “American zone,” today the Hongkou district, indicating they were ship crew, military personnel, or merchants of shawls waiting for their next connection to Manila in the Philippines. The record of the first Spanish women dates to the late 19th century, when Spanish families began settling at the mouth of the Yangtze River after Spain lost control of the Philippines.

These Spaniards gathered in Jerónimo Candel’s store, La España, located at 59 North Sichuan Road. Although his millinery shop and grocery store have long since vanished, the surrounding buildings still maintain the Art Déco style that defined the era.

To the north, away from the tourist circuit, in one of the city’s best-preserved areas with small antique shops and huntun soup stalls, stands a little Alhambra. At 250 Duolun Road, the lobed arches, geometric details, and blue mosaics seem out of time and place. The horseshoe-shaped building, with clothes drying in the sun and neighbors chatting in the porches, recalls a Mediterranean landscape. A plaque, placed thanks to the Shanghai Cervantes Institute, tells of its former owner: the cinema magnate Antonio Ramos, originally from the Spanish province of Granada.

According to the researcher Juan Ignacio Toro, Ramos arrived in Shanghai after 1899 with the first cinematographs under his arm. He began projecting moving images in tea houses located in the red-light district on Fuzhou Street (which since Maoism has become a cultural avenue with bookstores and shops selling calligraphy and stamps). Unlike his competitors, his films sought to attract a Chinese audience with historical themes, such as the death of Empress Dowager Cixi. His success was resounding.

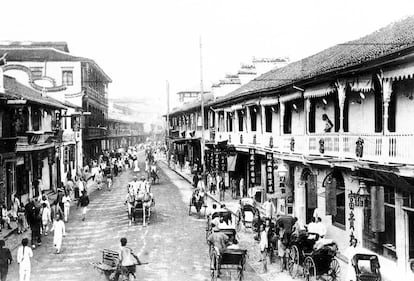

Shanghai in the 19th century. Pictures from History / UNIVERSAL IMAGES / GETTY IMAGES

Shanghai in the 19th century. Pictures from History / UNIVERSAL IMAGES / GETTY IMAGES

Next to his summer mansion, built in 1924, the Ramos Apartments —one of his real estate investments — also still stand. This residential block with French-style balconies housed Lu Xun, the most influential Chinese writer of the 20th century.

Ramos owned seven movie theaters throughout the city, including the country’s first modern cinema house, the Hongkew. In its place, the government built a promenade honoring the stars and pioneers of what was once the Hollywood of the Far East.

In 1927, at the height of the Chinese Civil War, Ramos set off for Madrid, where he founded the Rialto Theatre on the city’s Gran Vía avenue. Originally, the cinema’s name was a tribute to the distant port where he had made his fortune: Shanghai.

The king of ballrooms

In a city that just wanted to have fun, a Madrid-born architect created the stage for its wildest nights. During the 1920s, Abelardo Lafuente designed houses, renovated hotels and envisioned chapels, but above all, he was renowned for his ballrooms.

The former Hotel Astor — now the Stock Exchange Museum — located at number 15 Huangpu Street, no longer hosts parties, though echoes of the jazz that played more than a century ago still linger. This stately building on the riverbank hides the city’s only surviving ballroom designed by Lafuente. With an arched wooden floor designed to mimic the rhythm of the music and a false ceiling that enhanced the acoustics, the dance hall opened its doors in 1917, four years after Lafuente’s arrival from Manila.

Interior view of the Hotel Astor.Steve Vidler (Alamy / CORDON PRESS)

Interior view of the Hotel Astor.Steve Vidler (Alamy / CORDON PRESS)

Researcher Álvaro Leonardo-Pérez, who rediscovered Lafuente’s legacy, highlights that the architect introduced the neo-Mudéjar style to a city eager for exoticism. Leonardo-Pérez — who designed Ramos’s mansion and apartments — also left other surviving works, such as the Kincheng Bank (Jiangxi 200) and the Rosenfeld family villa at Dongping 11, where an upscale restaurant now revives the elegance of yesteryear.

Like the cinema entrepreneur, Lafuente was forced to leave the country in 1927 due to clashes between the communists and nationalists. He pursued his career in the United States, but never gained much recognition. A few years later, contemporary reports celebrated his return to the “Paris of the East,” though shortly after arriving, he died from a lung disease contracted during his journey from California.

The transportation mogul

At night, the lights come alive on West Nanjing Street. But don’t be fooled by the shopping centers and luxury stores — there’s a building that commands attention. At number 702, the Arabic arches, wooden latticework, and the ornate lettering of its old name — the Star Garage — stand out. Like an Andalusian fantasy, imagined by Lafuente for Albert Cohen, this building was constructed to house rickshaws and rent out the city’s first automobiles. Located next to what was once the Jewish club, the garage was one of many properties owned by this millionaire.

Cohen — a Sephardic Jew from Spain — made his fortune with a mode of transportation that embodied the colonial tensions of the time: the rickshaw, a two-wheeled cart pulled by a person. His company, with thousands of uniformed employees roaming the city, monopolized the sector. Cohen was the owner of rental buildings, laundries, and three garages, and it’s said he even lent his car to the Spanish consul so he could travel around the city in a style fitting of his status.

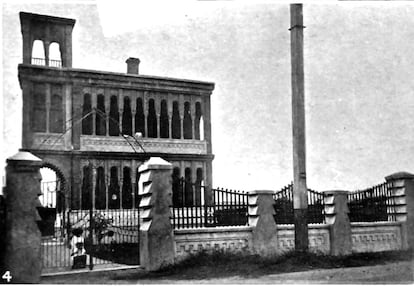

One of the buildings designed by Abelardo Lafuente.WIKIPEDIA

One of the buildings designed by Abelardo Lafuente.WIKIPEDIA

In A Novelist’s Journey Around the World (1924), Vicente Blasco Ibáñez recounted a dinner at the old consulate (now Huaihai 1431), where he met the three most prominent Spaniards in the city. But the real celebrities were the pelotaris — the athletes who played Basque pelota. They never missed an opening and brought prestige to any party.

Some of that swagger still lingers in the walls of what was once the most popular frontón, a type of court for Basque pelota, the Auditorium at South Shaanxi 132, which still retains its original staircases. “Small but prestigious,” was how Blasco Ibáñez described this Spanish community that, though unlikely, still reveals its history today in the streets of Shanghai.

Lucila Carzoglio and Salvador Marinaro are authors of the Instituto Cervantes Guide to Shanghai and co-editors of Chopsuey magazine.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition