Anyone with a collector in their family knows how easily it can become an obsession. In A Noble Madness: The Dark Side of Collecting from Antiquity Until Now (Riverrun), James Delbourgo explores the dark mania of the “mad collector”. This witty, anecdote-filled history ranges across the ages, taking in notorious real-life collectors (Adolf Hitler for art; Imelda Marcos for shoes) and fictional ones (such as Psycho’s Norman Bates).

Adam Sisman’s thorough biography The Indefatigable Asa Briggs (William Collins) astutely pieces together what was a more turbulent life than you might expect from one of the best-known historians of his generation. Briggs, who died in 2016, was certainly on to a good thing when it came to the fees he received. In 1973, he was paid £230,000 (in 2025 values) to write a history of the Bethlem Hospital. He proceeded to string along his commissioners for the next quarter of a century, to the point where they had to hire other historians to finish the book. None of the final content was credited to any one individual, “to conceal that Asa had contributed so little,” in Sisman’s words. You almost have to admire Briggs’s chutzpah.

One can only imagine what Briggs, a founder member of the Society for Anglo-Chinese Understanding, would make of China in the 2020s. Dan Wang’s engrossing Breakneck: China’s Quest to Engineer the Future (Allen Lane) presents a disturbing picture of reality there. Life during Covid is the subject of one captivating chapter. In addition to censoring stories and press during the pandemic, China’s rulers used intrusive surveillance to control the population: government drones followed those not wearing masks and projected lights onto people standing on their balconies, as a megaphone barked the order: “Do not open your windows to sing, it can spread the virus.” Orwell’s Oceania is alive and kicking. Another non-fiction book I would recommend is Lucy Inglis’s compelling Born: A History of Childbirth (Bloomsbury Continuum). A nod, too, for Buckeye (Bloomsbury), the debut novel by talented short story writer Patrick Ryan. It is a poignant, powerful exploration of smalltown America.

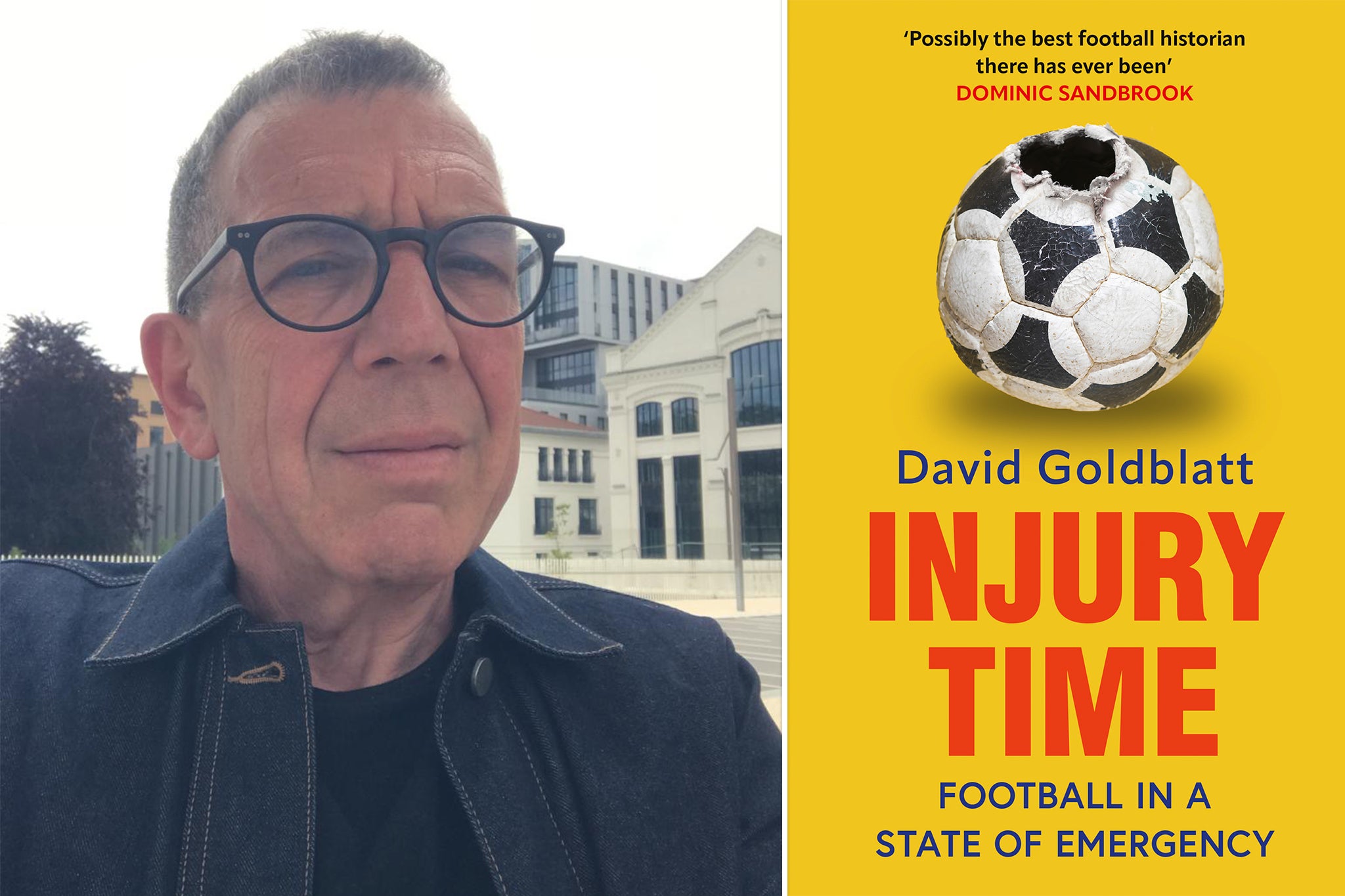

Non-fiction Book of the Month: Injury Time: Football in a State of Emergency by David Goldblatt

★★★★☆

open image in gallery

Goldblatt deals with the pernicious, perilous state of the modern game (Harper Collins)

Author of the first-class 2015 book The Game of Our Lives, David Goldblatt is one of the UK’s most acclaimed writers of complex football history books. His new publication, Injury Time: Football in a State of Emergency, timed for the start of a new season, deals with the pernicious, perilous state of the modern game. The book is divided into three sections: football after the Brexit referendum (2016-19); in the time of Covid (2020-22); and its current “state of emergency” (2022-24), during the “polycrisis” of a tanking economy, global conflicts, climate change, and the rest of the stuff that cheers us all on a daily basis.

Such a broad canvas allows Goldblatt space to make incisive points about numerous enduring problems afflicting football, including prejudice. He calls racism “football’s dirty secret”, and cites cases where the Football Association seem to have absolved people with a record of sending racist messages. Goldblatt also makes a pertinent point about the encoded racism of modern football commentary.

In this “state of the nation” book, Goldblatt pulls apart the many ways in which the game is failing – its treatment of youth players, a decline in respect for referees, and unregulated club ownership – and offers a sharp account of the consequences of the gambling epidemic. It is also disturbing to read about the environmental wastefulness of football clubs. According to Uefa, in a report Goldblatt mentions, 60 per cent of all apparel purchased by clubs is never even used. It ends up being “dumped or burned”.

Modern football is also blighted by an atmosphere of tawdry money-making. The author highlights the ways that high-earning players seek extra income from sideline hustles, including by endorsing cryptotrading tokens. Of former Manchester United star Paul Pogba’s promotional work for “Cryptodragons”, the author notes that “one can only hope it did better than John Terry’s Ape Kids Club FC, which was flogging gruesome football-themed baby ape cartoons for around £150 a pop”.

Injury Time is a forceful, informative read. And if football really is a mirror of the state of society, then we truly are as sick as a parrot.

‘Injury Time: Football in a State of Emergency’ by David Goldblatt is published by Mudlark on 14 August, £22

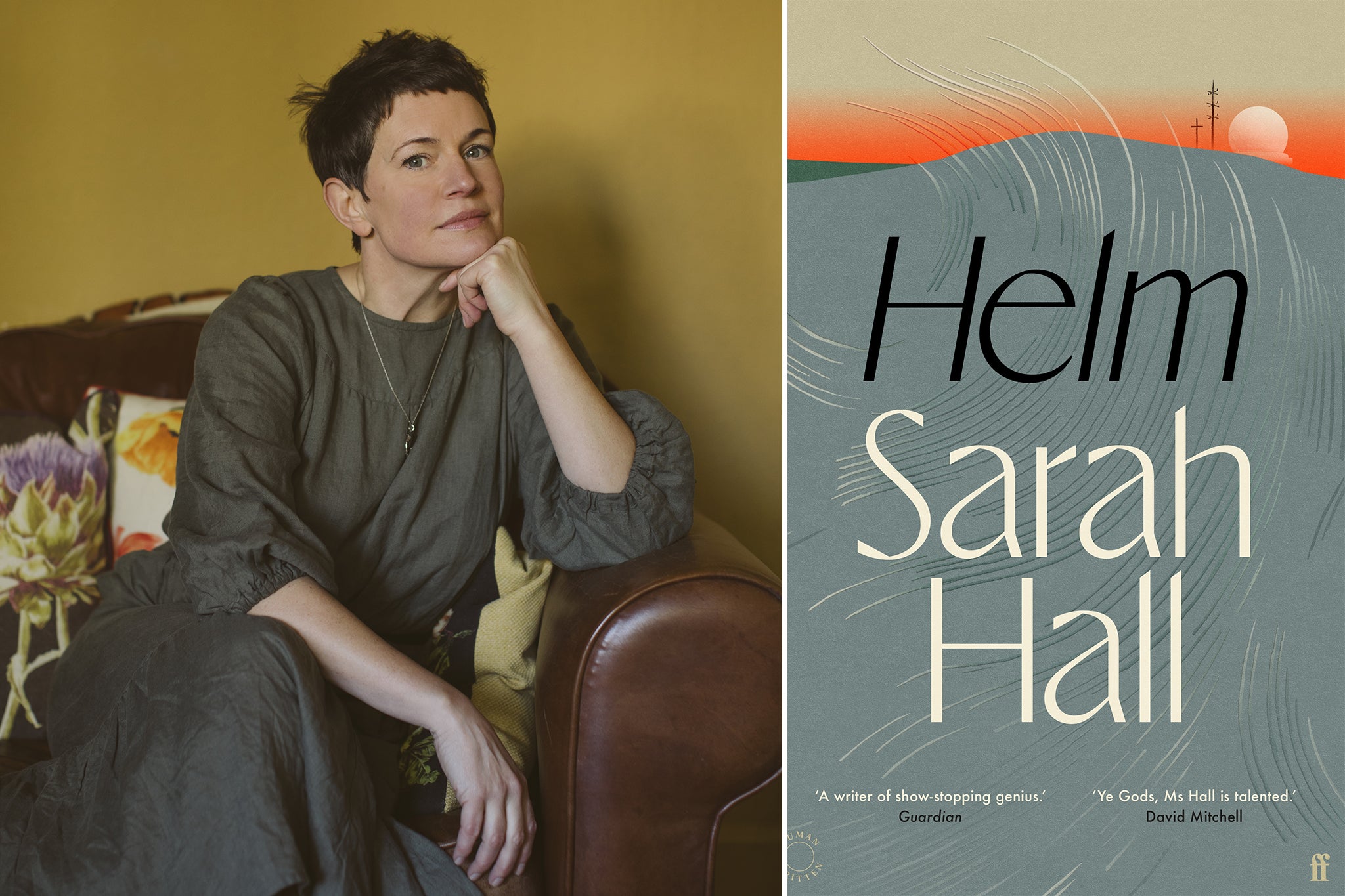

Novel of the Month: Helm by Sarah Hall

★★★★★

open image in gallery

Hall’s witty new novel examines the relationship between people and the natural world (Kat Green/Faber)

Sarah Hall is a writer bold and talented enough to pull off a novel in which the main character is the wind itself. In the case of Helm, Britain’s only named wind, it is the blustery northeasterly gust that blows down the western slope of Cross Fell, the highest peak in the Pennine Hills.

Hall has said wind demons were considered to be “perverts” in King James I’s Demonology – and Helm, a genderless sort of narrator of the novel, is puckish and Rabelaisian, although not obviously perverted. We are told “Helm loves a fart joke” and that he enjoys looking down on humans and the entertainment we provide, including the Neolithic tribe that tries to placate him. One of the reasons he enjoys watching this “fantastic theatre” of human behaviour is because “they biff and boff and booze”.

There is plenty of “boffing” in the lively chapter about a couple who have sex in a Victorian hot air balloon. The contraption makes Helm think of an “unearthly bladder” as it hangs above a valley in the Pennines. Hall wryly describes Henry and Claudine’s copulation as “the first-ever act of the mile-high club”.

Carlisle-born Hall has previously shown a shimmering ability to conjure her native landscape in immersive storytelling – I loved her 2021 novel Burntcoat, which was one of my picks for 2021 books of the year – and the Cumbrian countryside is a constant delight in Helm, a novel that examines the relationship between people and the natural world in a highly original way.

Hall’s humour blows throughout. I loved the wind’s diatribe against “those appalling f***ers” – the twin-engine RAF Tornado fighter jets whose rapid flight is described in Hall’s usual stylish, thrilling prose. Another chapter full of panache is “Helm’s Wind-Force Scale”, which details the 12 wind speed categories. Even at No 4 (“Moderate Helm, wind speed 13-18mph”), there is nothing much more to worry about, Hall states drolly, than “Women’s Institute beanstalk alerts”. If it escalates to No 12, we can all start panicking. “‘Hurricane Helm (wind speed 73-83mph)” will bring “Carlise-Settle train lifted off the tracks” and “Eden reconfigured”. The finale of the novel deals with the worsening climate and the threat to Helm’s very existence from pollution. Helm, which was 20 years in the making, will sweep you off your feet.

‘Helm’ by Sarah Hall is published on 28 August by Faber, £20

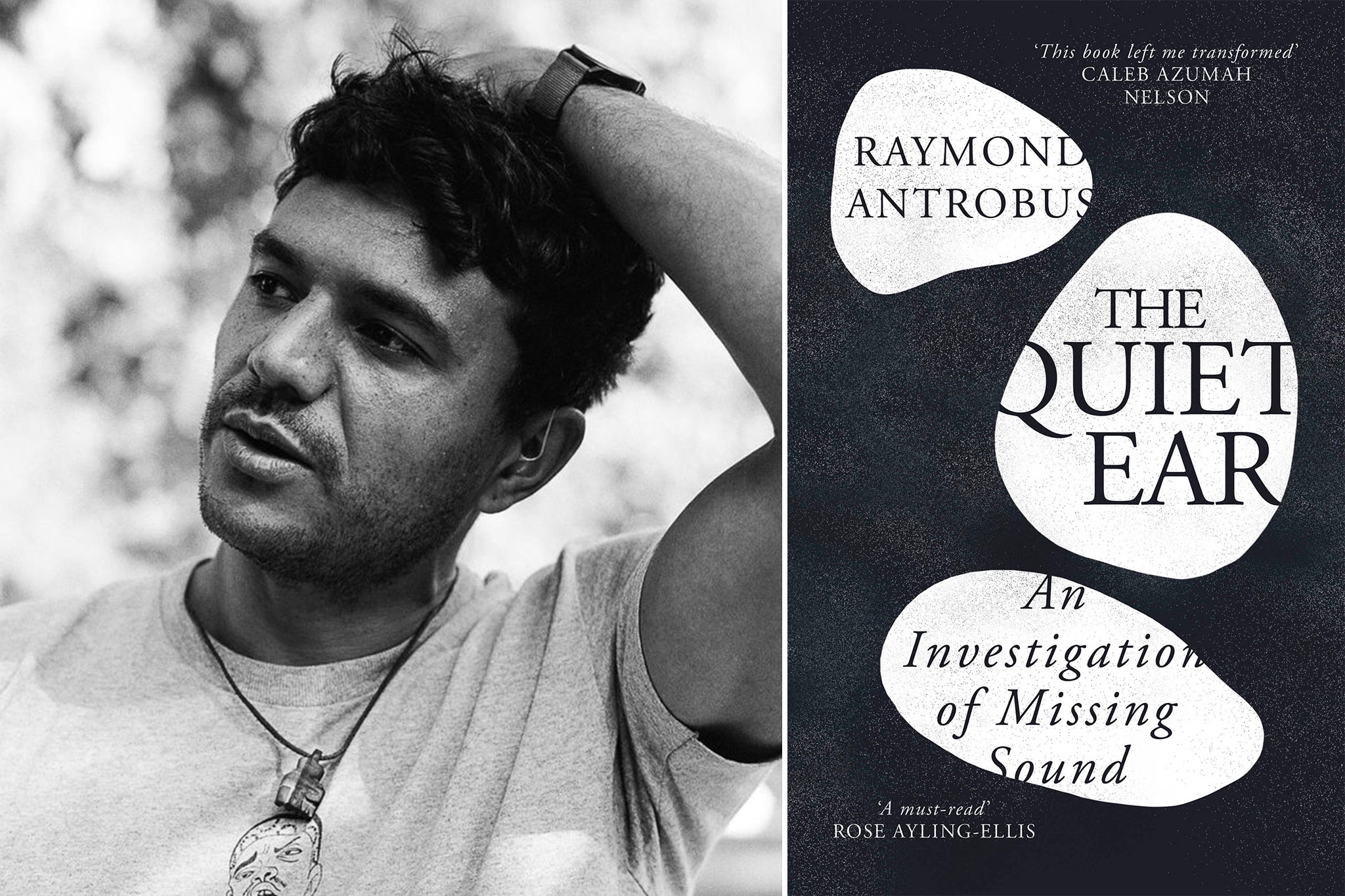

Memoir of the Month: The Quiet Ear: An Investigation of Missing Sound by Raymond Antrobus

★★★★☆

open image in gallery

Antrobus’s book is a moving story of personal struggles (Orion Books)

More than once, the award-winning poet Raymond Antrobus has been told: “You don’t look deaf”. It’s an extraordinarily insensitive comment, and one of many moments in his memoir The Quiet Ear: An Investigation of Missing Sound that should force readers to pause and reflect.

Antrobus, the son of an English mother (his surname is from an ancestral village in Cheshire) and Jamaican father, was diagnosed with deafness at the age of six. His book offers a rich, enlightening examination of deafness – and why it sometimes left him feeling “ugly and incapable”. His wry asides include the observation that “there is something English about the way silence can carry any heavy suppressed emotion”.

The book is, in part, a moving story of personal struggles – he recalls that “it took me years to reframe my deafness as a gain rather than a loss” – as well as an honest account of dealing with prejudice both about race and “disability”. I enjoyed the gently humorous tone he brought to his history, exemplified in a section about a deafness poem written by Ted Hughes. I won’t spoil that particular tale, which involves a redacted version.

The Quiet Ear is packed with surprising stories – including about how deaf boxer Reece Cattermole functioned in the ring, and how deaf singer Johnnie Ray coped on stage – and, above all, it is an honest, revelatory account of Antrobus’s own path to poetry, of his violent father and of the hidden problems facing those that are deaf. Antrobus repeats a statistic that 95 per cent of people born deaf in Jamaica grow up illiterate. In the UK it’s around 70 per cent.

Antrobus’s book also shines a light on deaf education in Britain. One of the most poignant moments is when he recollects how a headteacher in a deaf school told him that some parents are ashamed of their child’s deafness, remarking that “they spoke like grieving parents”.

‘The Quiet Ear: An Investigation of Missing Sound’ by Raymond Antrobus is published by Weidenfeld & Nicolson on 28 August, £16.99