Supporters of free scientific research in Sacramento, California, on March 7, 2025.

Penny Collins / Nurphoto

Listen to the article

Listening the article

Toggle language selector

Generated with artificial intelligence.

As the United States cuts funding for science and threatens universities, many researchers are looking to relocate, and Europe is rolling out the red carpet. Switzerland, however, is not trying to woo them.

This content was published on

August 4, 2025 – 09:00

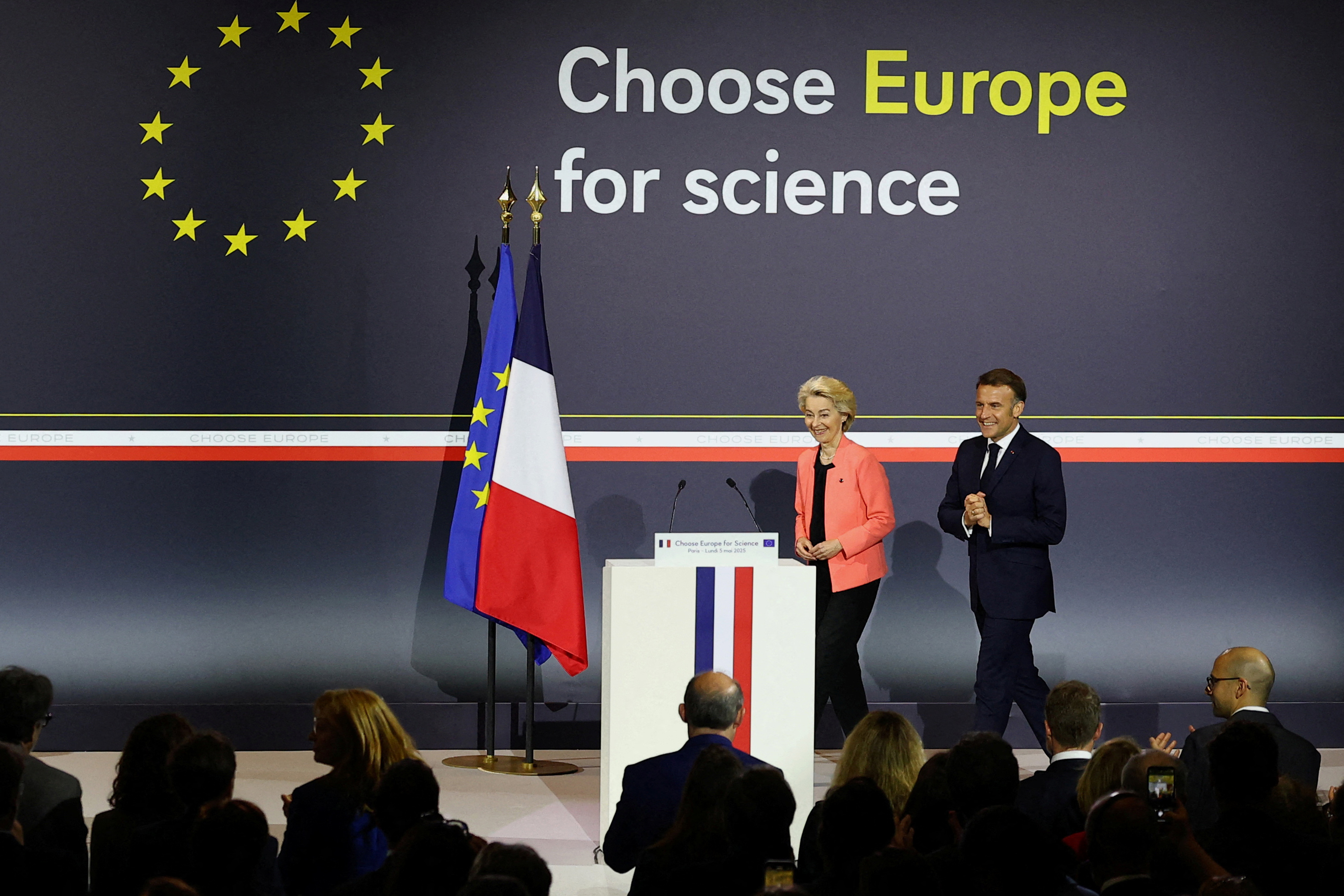

This spring, set against the historic backdrop of the Sorbonne University, French President Emmanuel Macron and European Commission President Ursula Von der Leyen rolled out a €500 million (CHF466 million) welcome mat for American scientists.

Their efforts are a response to the US government’s cutting billions of dollars in funding for science, rejecting settled research in medical policy, and pressuring universities to change their curricula. The EU’s “Choose Europe for Science” plan is the first centralised initiative to attract international scientists onto European soil, augmenting individual countries’ efforts to lure American researchers to more supportive institutions abroad.

French President Emmanuel Macron and European Commission President Ursula Von der Leyen on stage announcing the “Choose Europe for Science” initiative.

Gonzalo Fuentes / AFP

But non-EU-member Switzerland is not taking part in the new scheme and is not planning any similar initiatives of its own. Many Swiss-based researchers and institutions see such actions as opportunistic and superfluous for a research system they believe is already attractive enough to outside scholars. The Swiss State Secretariat for Education, Research and Innovation (SERI) called the EU’s program “a contradiction to the principle of competition and excellence in higher education,” in comments to Swiss Public Television SRF. But others in Switzerland believe the US crisis could offer a unique opportunity to attract bright minds and bolster the competitiveness of the Swiss research ecosystem.

Researchers pushed away by the US

The US has long been the world’s science superpower. Government money accounts for nearly $200 billion of a total of $900 billion spent on research and development in the country each year, accounting for about 3.6% of GDP. Europe as a whole spends $500 billion, while Switzerland invests about $31.3 billion annually, or 3.4% of its GDP.

Since President Donald Trump took office in January 2025, the US federal government has cancelled thousands of grants and plans $43 billion in cuts by 2026, especially at institutions like the National Institutes of Health (the biggest health-related research body in the world) and the National Science Foundation.

The Trump administration is also threatening to defund scientific institutions and universities if they continue to conduct research or run programmes related to diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI), as well as vaccines and climate change. Other topics, such as AI and quantum technology, remain top priorities in the government’s agenda.

Claudia Brühwiler, a political scientist focused on American studies at the University of St Gallen, sees this as an unprecedented attack on academic freedom. She recently told the Horizons magazine that the US government has, “in the name of freedom of speech, been cutting down freedom of speech, freedom of ideas and freedom of research”.

The Association of American Universities (AAU) said in March that “the withdrawal of research funding for reasons unrelated to research sets a dangerous and counterproductive precedent”.

“It’s a very difficult situation for people working on immunology and virology. US colleagues fear losing their grants, some of them were locked out of their labs, others left academia altogether,” says Volker Thiel, a virologist at the University of Bern’s Institute for Virology and Immunology (IVI).

In March, three prominent Yale scholars decided to leave the US for Canada, citing fears over Trump administration policies. Also in March, 1,200 of 1,600 US-based researchers who responded to a poll by the science journal Nature said they were considering moving abroad.

Europe responds to US cuts

European countries responded to the possible exodus with initiatives at the local, national, and EU levels. Aix University in Marseille moved first, allocating €15 million for foreign researchers working on climate, health, environment, and social sciences. France was also active in pushing for the “Choose Europe” program, which will run until 2027. Spain has opened its purse with a programme worth €50 million per year. And Germany pledged to launch the program “1000 Köpfe” (1000 heads), which aims at attracting not only émigrés from the US system, but also researchers who were destined for the US and are now looking elsewhere. In May 2025, the European Research Council (ERC) doubled the additional funding available for grantees relocating to Europe, from up to €1 million to up to €2 million.

“The ERC Scientific Council raised this “start-up” funding to try to help researchers based in the US in their current situation, but it is of course open to everyone worldwide moving to Europe,” said ERC President Maria Leptin.

None of these investments come close to matching what the US government is cutting, and critics worry that these initiatives won’t be enough to make up the significant gap between Europe and the US when it comes to R&D expenditure.

“I have my doubts that Europe would be able to attract a lot of US scientists, as the academic salaries are way too low in most of Europe,” says Marcel Salathé, co-director of the AI Center at the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology Lausanne (EPFL).

Switzerland is still attractive from a salary point of view, Salathé adds. The average salary for a full professor in the US is above $150,000, while in most European countries it is well below €100,000. In Switzerland it can go above CHF200,000.

The Swiss approach: we are good enough

In the face of all these EU initiatives, Swiss institutions have responded with a shrug. “We know that talented scientists from all over the world are attracted by attractive research environments, high academic standards, and international cooperation. Our universities offer such conditions and are therefore in a good position to compete for talent,” a SERI spokesperson told SRF.

According to the Swiss Federal Statistical Office (FSO)External link, of the 4,793 professors in the Alpine country’s 12 universities and two federal institutes, more than half come from abroad, and 121 of them are US citizens. Many foreign professors teach and research at the federal technology institutes ETH Zurich (66% of the faculty is non-Swiss) and EPFL (70%). The same institutions, together with the University of Zurich, are home to two-thirds of all US-born professors in Switzerland.

Switzerland also emerged as a preferred destination for some of the scientists who responded to the Nature poll, a trend corroborated by Swiss institutions.

“ETH Zurich, like other Swiss universities, has received an increasing number of applications from researchers in the United States in recent weeks and months,” spokesperson Markus Gross told Swissinfo.

Don’t poach if you don’t want to be poached

It’s not just confidence in the existing system that keeps Switzerland from wooing American scholars.

At a press conference in April, Joël Mesot, President of ETH Zurich, said that when Switzerland was excluded from Horizon Europe, the EU’s €95.5 billion research and innovation programme for 2021-2027, other countries offered financial incentives to lure Swiss researchers.

“We do not want to play a similar game with the US. It would not be ethical to do this, and we don’t want to engage in unethical practices.”

But not everyone agrees with Switzerland’s hands-off policy. “We’re missing out on some really good opportunities, made possible by this externally created window. The best people would probably come relatively soon if we opened our doors to them with the corresponding funding,” Salathé says.

Cuts looming for Swiss science

Meanwhile, Switzerland is facing its own hurdles in funding the scientists it already has. The federal government, aiming to bring the federal budget into balance, is eyeing cuts to education, research, and innovation that amount to more than CHF460 million per year (with ETH and EPFL facing annual savings of CHF100 million from 2025). The move was harshly criticised in a position paper from top Swiss academic institutions, including ETH Zurich’s board and the Swiss National Science Foundation (SNSF), last February. According to them, the proposed cuts could have serious consequences for the Alpine nation’s ability to maintain its competitive edge in research and innovation, including its appeal to the best scientists.

“I’m not sure if Switzerland can do anything to attract US scientists, because we don’t even have positions for the people who are here,” Thiel says. Even if funding were there, convincing established senior US scientists would mean offering them a competitive package that may include the leadership of an entire institute, he argues. He thinks early- career researchers might be easier to attract.

Thiel sees some hope in the fact that the Swiss government and the EU commission are heading towards an agreement that would grant Switzerland full access to Horizon Europe and ERC funds. Since this year, researchers who are affiliated or are willing to affiliate with Swiss institutions have been able to apply for prestigious ERC grants, and ERC schemes aimed at those relocating to Europe could offer US scientists the attractive package they are looking for.

There’s also the promise of broad collaboration and freedom which EU President von der Leyen sees as key reasons to choose Europe. If the US cuts to science and pressure on universities continue, other countries will become increasingly attractive.

“US leadership in research is questioned right now. And if Switzerland and Europe can at least keep up with the current resources and the scientific level, we may gain more weight,” Thiel says.

More

What’s the smartest way for countries to compete for world-class research talent?

As the US slashes science funding and pressures universities, many researchers are considering a move. Should Switzerland try to entice them?

View the discussion

Edited by Gabe Bullard/vdv

Articles in this story