Every cat lover knows the uncanny ability of our furry companions to land on their feet – a talent so iconic it became an idiom. It turns out, not only did it once baffle the finest scientific minds in history, but this mysterious feline feat also played a role solving an important challenge in the NASA space programme.

But let’s not get ahead of ourselves.

Now, we’ve all seen it. That moment when the cat – while twisted into a pretzel to clean itself – overbalances and falls off the back of the sofa, or from a shelf they shouldn’t even be on. Somehow, during that brief moment they’re airborne, they manage to twist mid-air, hitting the floor paws-first with little more than a look of mild indignation. It’s a party trick that seems to defy the laws of physics.

How cats baffled physicists

So back to those scientists. Back in the 19th century, the great minds of the time weren’t just pondering electromagnetism or fluid dynamics, they were also dropping cats. One such mind was James Clerk Maxwell, the Scottish physicist whose equations underpin our entire understanding of light and electromagnetism. While studying at Trinity College, Cambridge, Maxwell earned a reputation for being rather too interested in how cats fall. “There is a tradition in Trinity,” he wrote to his wife in 1870, “that I discovered a method of throwing a cat so as not to light on its feet…”

Maxwell insisted, of course, that he never hurled cats out of windows. The proper method, he claimed, was letting them drop just two inches onto a bed. It’s a relief to know that scientific curiosity has its boundaries, and that no cats were harmed in the making of these experiments.

He wasn’t alone. Fellow physicist and mathematician George Gabriel Stokes, another Cambridge luminary, was also baffled by what he called the “cat-turning” problem. Their concern wasn’t for feline wellbeing (hopefully that was a given), but for what seemed to be a troubling violation of Newtonian physics: how can a cat, released with zero spin and no external forces, begin to rotate in mid-air?

At the time, this seemed impossible. Conservation of angular momentum – the same principle that keeps ice skaters spinning faster when they pull their arms in – says that an object can’t start rotating unless something pushes or pulls on it. And yet, cats did. Repeatedly.

A breakthrough in motion

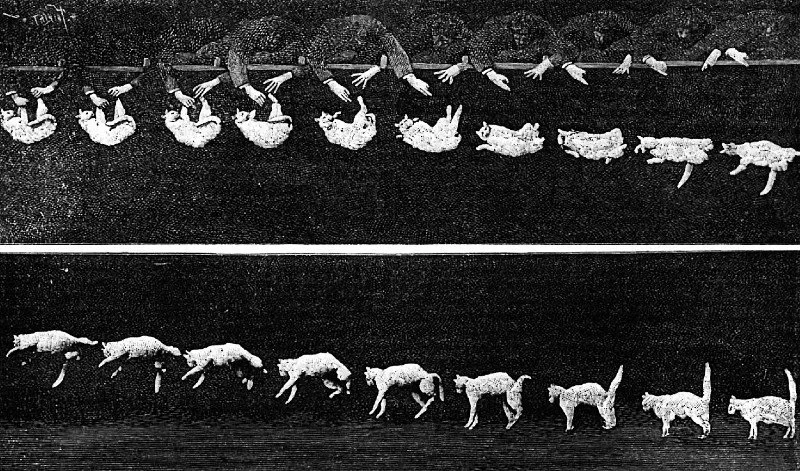

It wasn’t until nearly 50 years later that any real scientific progress was made, thanks to a Frenchman, a camera, and (of course) another airborne cat. In 1894, Étienne-Jules Marey, a physiologist and photographic pioneer, developed a technique called chronophotography to capture motion in multiple frames per second. One of his most famous images shows a cat, suspended upside down, being dropped. Frame by frame, you can see the cat twist and realign until, miraculously but predictably, it lands on its feet.

Chronophotographic method in 1894 captured a cat twisting mid-air to land on its feet. Images by Étienne-Jules Marey via Wikimedia Commons (CC0)

Chronophotographic method in 1894 captured a cat twisting mid-air to land on its feet. Images by Étienne-Jules Marey via Wikimedia Commons (CC0)

This wasn’t just an elegant sequence of photos. It blew a big hole in the prevailing theory that the cat used the handler’s hands as a sort of twisting platform. Marey’s images showed the cat had no initial spin. It was acquiring angular momentum after being released, all on its own. Somehow.

Marey speculated that the cat cleverly manipulated the moment of inertia in different parts of its body, first tucking in its front legs while stretching its rear ones, then switching. This idea was remarkably close to the truth, but not yet complete.

Still, many physicists remained unconvinced. Some dismissed the entire thing as an illusion. It wasn’t until 1969, the same year Neil Armstrong took a giant leap for mankind – and thankfully landed on his feet – that the “falling cat problem” was finally solved.

Which brings us to the twist in the tale, courtesy of NASA.

A cosmic twist

In the 1960s, space scientists had a new problem: how could untethered astronauts rotate or orientate themselves in the zero-gravity environment of space? Enter T.R. Kane and M.P. Scher, two researchers at Stanford University. With NASA’s support, they revisited the feline puzzle (just imagine the grant application: ‘To determine how cats land on their feet… for space’).

Their breakthrough was to model the cat not as a rigid body, but as two flexible segments joined in the middle – a perfect metaphor for the supple spine of a real cat. When the cat bends at the waist, it effectively creates two separate systems: front and rear. By tucking in one end and extending the other, the cat can rotate each half in opposite directions, all while conserving momentum. The result? A smooth aerial pirouette and a landing as graceful as Apollo 11’s Lunar Module Eagle touching down on the moon.

Thanks to this research, astronauts learnt how to reorientate themselves mid-flight, using exactly the same principles your average moggy employs when falling off the kitchen worktop.

No wonder the Soviets lost the space race. They sent up dogs. It turns out it’s the humble cat that’s zero-gravity-ready.

A paw-some tribute

So this International Cat Day, as we celebrate the purring, prowling enigmas who grace our homes – and occasionally leave us unwanted gifts – let’s raise a paw to their remarkable physics, and to the fact that long before they inspired memes and internet videos, cats were quietly helping humanity reach for the stars.

More from East Anglia Bylines Download the Bylines app to get our content straight to your phone!

Download the Bylines app to get our content straight to your phone!