Life is art. There are few artists for whom that’s more true than for Picasso. You can chart the ups and downs of his romances through his canvases — and establish overlapping timelines; you can assess his emotional state; you can estimate his affluence (consistently increasing) or the size of the space he’s working in (ditto). Even his interior scenes function as a kind of self-portrait.

It’s interior spaces that form the backbone of the forthcoming exhibition at the National Gallery of Ireland (NGI), Picasso: From the Studio. Curated with the Musée Picasso in Paris, with a large number of loans from that elegant institution, it takes a chronological journey through the Spanish artist’s career, via the key locations in France in which he worked.

It will look at how the artist’s environment influenced his output, from soon after his arrival in Paris from Barcelona at the start of the 20th century to his last home and studio at Mougins, through paintings, sculptures, ceramics and works on paper, photography and rarely seen film. There are more than 150 recorded places that Picasso made art throughout his life, but the exhibition begins around 1912, as Picasso and Georges Braque were egging each other on to develop cubism. Small assemblages and collages from this time, including the gallery’s own 1913 collage Bottle and Newspaper, will feature alongside works made of scavenged materials: paper scraps, stencilled letters, canvas, wood, pliable tin, nails, sand and paint.

Picasso’s Woman Reading, 1935

ADRIEN DIDIERJEAN/MUSÉE NATIONAL PICASSO-PARIS; SUCCESSION PICASSO/DACS, LONDON 2025; GRANDPALAISRM

These experiments show how the studio was “the laboratory of his work”, the exhibition’s co-curator Joanne Snrech says, but their modest size reflects the ad hoc spaces in which he worked — easier to lug around Paris to the next ramshackle spot.

By the Twenties Picasso was a success. He was collaborating with Serge Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes, and having married the dancer Olga Khokhlova in 1918 was a darling of society.

• Picasso or Goya: who created Spain’s most important painting?

As he holidayed on the newly fashionable Côte d’Azur, the sea, sunlight and the company of glam pals imbued Picasso’s work with a sunny exuberance. These paintings (because Picasso worked everywhere, even on holiday) exude the heat of the Riviera — a rare landscape made at his summer studio in Juan-les-Pins, where he and Olga stayed in 1920, or the jolly Still Life with a Mandolin from 1924, both in the show.

During the Thirties, though, all sorts of shifts happened. In 1927 Picasso, aged 45, had met 17-year-old Marie-Thérèse Walter outside a Paris department store, and started a relationship with her. In 1930 he bought a manor house at Boisgeloup in Normandy, about 45 miles from his Paris home, establishing a studio on the light-filled second floor, and began dividing his time between it and Paris. Olga stayed in the city with their son, Paolo, during the week, so the painter was free to have his young mistress visit him often in Boisgeloup.

They kept the relationship secret for eight years — goodness knows how, since Walter haunts his work throughout this period, her golden hair and almond-shaped eyes unmistakable even when distorted by cubism. Nearly all the show’s works from this studio depict her, including a serene portrait from 1937, two years after the birth of their daughter, Maya, at which time Picasso tried to divorce Olga (she refused; they stayed married until her death in 1955) — and around the time that he met the photographer Dora Maar, of whom, inevitably, more later.

Boisgeloup didn’t just enable the indulgence of a new muse. A large outbuilding allowed him to more intensely explore sculpture, especially monumental heads and busts. You can guess the dominant subject.

Head of a Woman, 1953

ADRIEN DIDIERJEAN/MUSÉE NATIONAL PICASSO-PARIS; SUCCESSION PICASSO/DACS, LONDON 202; GRANDPALAISRMN

His next studio was on the Rue des Grands-Augustins in the Saint-Germain-des-Prés district of Paris. Picasso liked it because the shabby 17th-century townhouse had a connection to Balzac as the residence for the painter Frenhofer, the main character in his novel The Unknown Masterpiece. It is where Picasso painted probably his second most famous work (the first being his 1907 masterpiece Les Demoiselles d’Avignon). Guernica was a commission from the Republican government for the Spanish pavilion at the 1937 Exposition Internationale in Paris.

• Read more art reviews, guides and interviews

Maar found the vast attic studio for him — partly thanks to it being a meeting place for the resistance group Contre-attaque, of which she had been a member — and secured exclusive rights to document the painting’s creation for the magazine Cahiers d’art. Quite different from Walter, whom the co-curator Janet McLean describes as “dreamy and romantic”, Maar was fiery and passionately left-wing, and as she documented his work, “they were bouncing off each other … it was a meeting of minds for sure,” her political zeal influencing the direction of the painting.

Sadly, Guernica doesn’t travel, but several works from the period give a sense of the tension and confinement of those difficult years. “I’m glad we’re able to show these quite frugal paintings made in 1938, when there were a lot of refugees coming to France due to the Spanish Civil War,” McLean says. One such is Child with a Lollipop Sitting Under a Chair, donated by Maya to the Musée Picasso a few years ago. Painted in sombre monochrome, “it’s not a pretty picture of a child”, McLean says; instead it has a huddled, claustrophobic feel. “It’s interesting to show Picasso connected to the world, because he really was.”

It’s not known why Picasso elected to remain in Paris as the Second World War intensified — he was unable to exhibit, the Nazi regime considered his work “degenerate” — but he kept working away in his attic, photographed there in 1944 by Brassaï. A shot from this series will be in the exhibition, alongside Bust of a Woman with a Blue Hat, a portrait of Maar made the same year, just after their not-quite-definitive break-up (they continued to see each other intermittently until 1946).

Bust of a Woman with a Blue Hat, 1944

MUSÉE NATIONAL PICASSO, PARIS © SUCCESSION PICASSO/DACS, LONDON 2025 © GRANDPALAISRMN

One of the aims of the exhibition, McLean says, is to show “Picasso’s versatility as an artist. While he considered himself primarily a painter, he was exceptional in his ability to turn his hand to any medium.” A wonderful example of this is his playful ceramics, influenced by the studio he took from 1948-55 at Vallauris, a small town on the Côte d’Azur.

It was home to a number of ceramic factories, depicted in Picasso’s 1951 canvas Smoke in Vallauris, where thick black puffs pump urgently into the sky from the wood-burning kilns. Inspired by Georges and Suzanne Ramié, the owners of the Madoura Pottery, he bought a villa nearby and set about learning from Suzanne, saying: “I don’t think I’m a ceramicist, next to ceramicists who are real ceramicists, I’m just […] an unfortunate amateur and an ignoramus. I try, I listen, I look, I try to pass my time.”

He produced more than 3,600 pieces in just a few years, several of which will be on display, including a dove modelled ingeniously out of a few flops of folded clay. He got so into it that an American newspaper referred to him as “left-wing ceramicist artist Picasso”. He was, at the time, active as part of the Movement for Peace and the French Communist Party. He enjoyed collaborating with his fellow artisans, and was active in the community, attending local bullfights and openings of pottery exhibitions, for which he designed the posters (free of charge), and portrayed his family life in pictures as part of a simple creative ideal.

• My journey through the French region most famous for its artists

A touching example of this is the 1954 canvas Claude drawing, Françoise and Paloma, a harmonious image depicting his two youngest children with their mother, the painter Françoise Gilot, whom he had met in 1943 (he 61, she 21) — except that Gilot is shown oddly only as an outline, curved protectively around her children. She had left him and returned to Paris with them the year before.

Still, his time in Vallauris was transformative for his output and for the town. In 1949 he donated his sculpture L’Homme au mouton (Man with a sheep) — it’s still on the market square — and in 1951 he created the War and Peace cycle in a local chapel. His presence, McLean says, “revitalised the ceramics industry in that region”.

Man of the people he may have been, but he was also very rich, and in 1955 he acquired La Californie, a des res in Cannes, where for the first time he lived and worked in the same space, which must have been inconvenient for his family (he had met his new partner, Jacqueline Roque, in 1952, when she was 26 and he was 70), given the rapid accumulation of artworks that filled every inch.

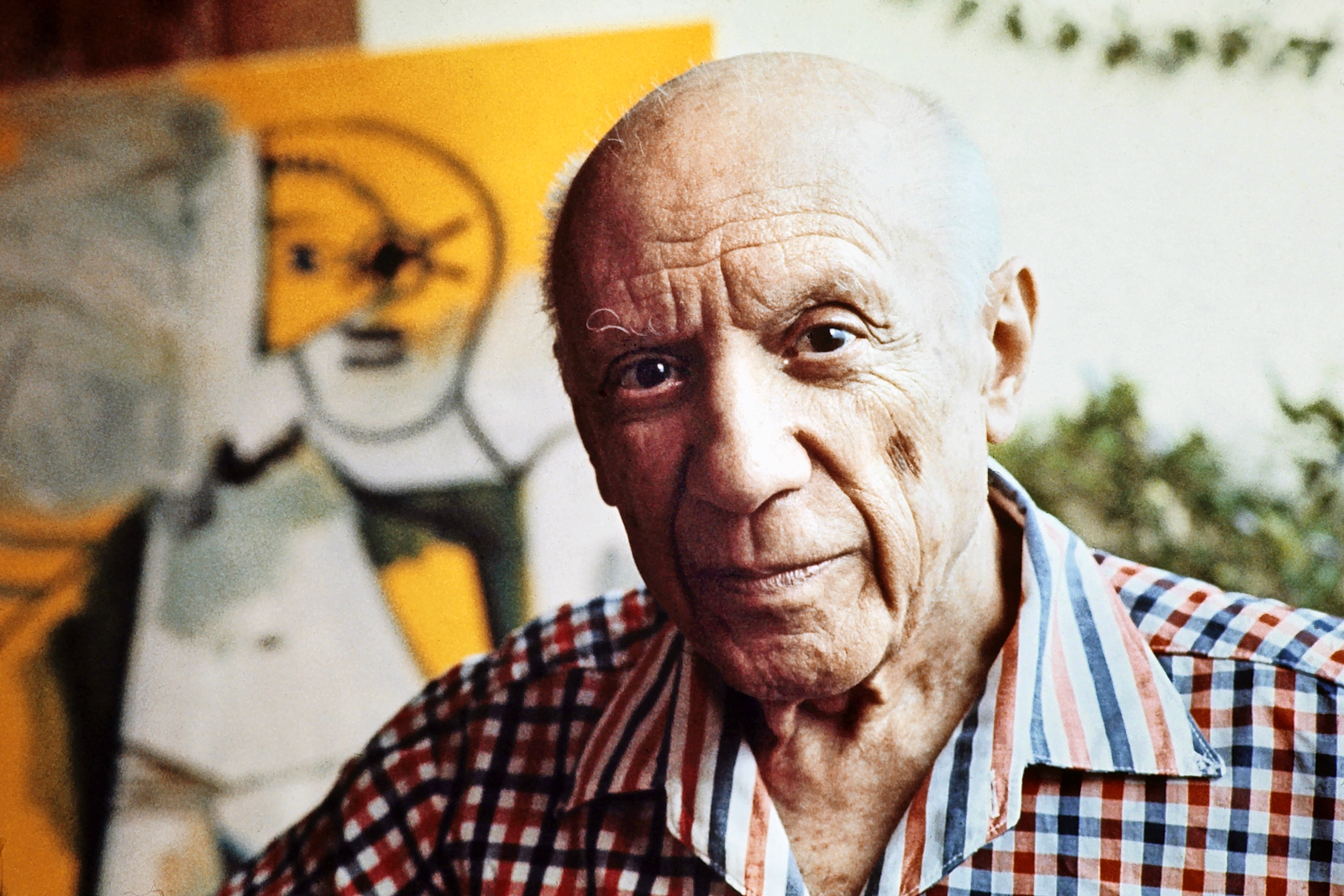

With Jacqueline Roque

ALAMY

The three adjoining rooms on the ground floor served as studio and living area, with rounded windows that opened onto a lush garden into which his sculpture spilled (the show features a great 1960-61 photograph of him there by André Sonine).

He seems to have seen La Californie as a sort of extension of himself, judging by the vigour with which he depicts it in his art. “This was the first time he had paid so much attention to his studio,” Snrech writes in the catalogue, “to the extent that these works can be seen almost as self-portraits.”

Several will be on display, including a magnificent 1956 canvas made in homage to Henri Matisse, who had died in 1954. The room is empty of people, but the painter’s presence is suggested by paintings and objects, and in the centre a blank canvas sits expectantly on an easel. Picasso called these paintings “interior landscapes”.

Eventually the lack of privacy in fast-developing Cannes drove him out. In 1961 — the year that he married Jacqueline at the town hall in Vallauris — he moved to his final studio, the Notre Dame de Vie farmhouse in the nearby town of Mougins. Surrounded by work from across his life (an entire wing was dedicated to the display of his sculptures), this was the scene of a final flowering, a period of insane productivity. He produced about 200 paintings between September 1970 and June 1972, and he created more portraits of Jacqueline than of any of his other partners.

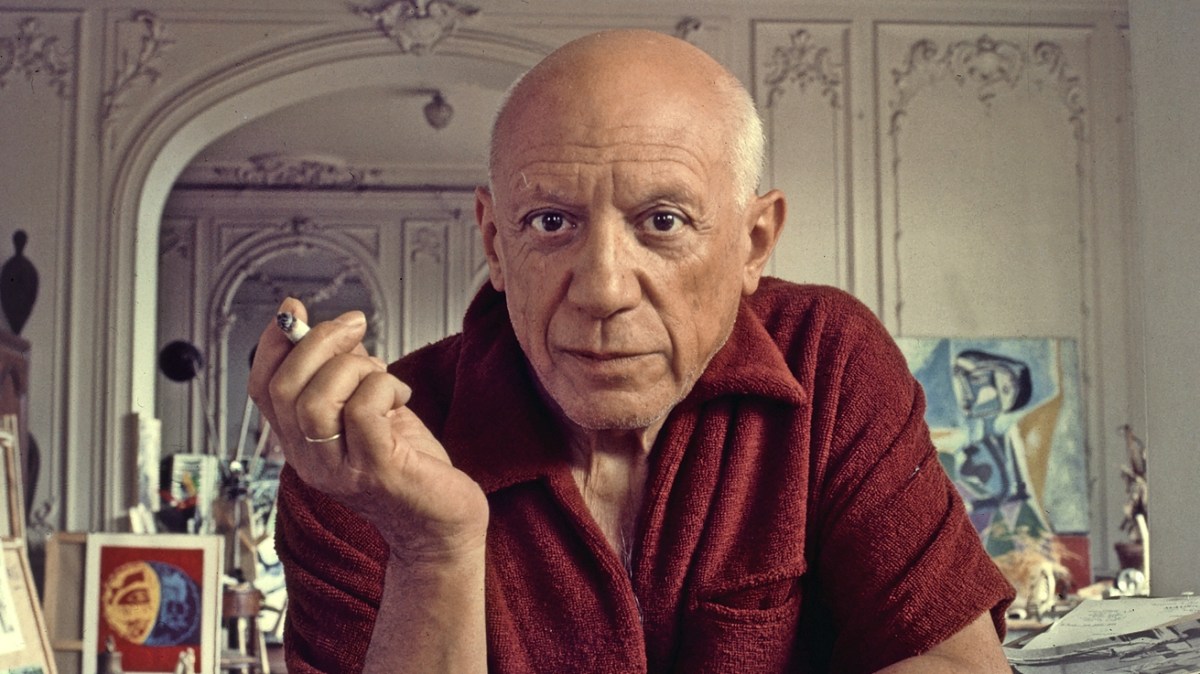

Picasso in Mougins, France, 1971

RALPH GATTI/AFP/GETTY IMAGES

In contrast to the hurly-burly of La Californie, he worked in relative solitude, assailed by memory — in a series of etchings, La Suite 347, created when he was 86, he returns to motifs such as bullfighters, circus performers, artists and models, mythology and literature, musketeers and animals — and by an urgent need to innovate, seen in the free, gestural brushstrokes of paintings such as Reclining Nude, 1967.

It was here that he died, in April 1973, probably from a heart attack. According to Paris Match, Jacqueline called his doctor in the early hours of the morning; he died a few hours later, at 11.45am, at the age of 91. There was no will, of course (not his problem), and more than 45,000 unsold works strewn across his various studios. An artist, first, foremost and only, to the last.

Picasso: From the Studio is at the National Gallery of Ireland, October 9 to February 22, nationalgallery.ie