Several villages and hamlets not far from Liverpool were uprooted – and their remains still lie hidden today

18:02, 10 Aug 2025Updated 18:02, 10 Aug 2025

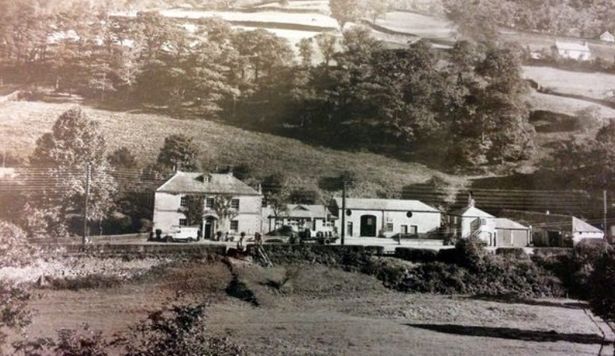

The farms and houses of the villages of Mardale and Measand and the well-loved Dun Bull Inn were demolished(Image: Topfoto/PA Images)

The farms and houses of the villages of Mardale and Measand and the well-loved Dun Bull Inn were demolished(Image: Topfoto/PA Images)

There’s a village less than an hour’s drive away from Liverpool that’s only visible when there’s a lack of rain. The strange phenomenon, known as ‘ghost’ villages, often appears during heatwaves from thirsty reservoirs.

This year’s dry spell and repeated heatwaves in a short timeframe have caused a severe drop in the water levels of several of the country’s reservoirs. And, although this is not good for the garden, it can be a rare opportunity to take a fascinating peek at the past.

Throughout the early part of the 20th century, the inhabitants of several villages and hamlets near Greater Manchester were uprooted, and their buildings were demolished, or sometimes left intact, to build reservoirs, reports M.E.N.

Sadly, it meant displaced residents have had to witness the demolition of their homes, churches, and streets as their close traditional communities are torn apart. But the remains of buildings and roads, often referred to as ‘ghost’ or ‘abandoned’ villages, can still be visible when a prolonged lack of rain shrinks reservoirs.

Mardale Green and Measand Mardale Green in 2018 (Image: Paul Wharton)

Mardale Green in 2018 (Image: Paul Wharton)

When the conditions are right, the remains of a village lost to supply Manchester with water reappear. During particular hot spells, the ‘drowned’ village of Mardale Green surfaces from its watery grave like ‘Atlantis.’

In the 1930s, the picturesque Lake District villages of Mardale Green and Measand were submerged to create what’s now known as the Haweswater reservoir. It was one of the largest reservoirs in England, meant to supplement the water from Thirlmere reservoir and supply Manchester with drinking water for a hundred years.

The controversial construction of the Haweswater dam in the Lake District started in 1929 after Parliament passed an Act giving Manchester Corporation permission to build the reservoir to supply water for the urban conurbations of northwest England. At the time, there was a public outcry about the decision, as the planned reservoir site was populated by the farming villages of Measand and Mardale Green.

Marsdale was submerged by Haweswater(Image: Topfoto/PA Images)

Marsdale was submerged by Haweswater(Image: Topfoto/PA Images)

In preparation for the villages being flooded, hundreds of people were forced to leave their homes, and 97 bodies were removed and re-buried in a graveyard in the nearby village of Shap. The farms and houses of the villages of Mardale and Measand and the well-loved Dun Bull Inn were demolished.

Despite being demolished and submerged by the reservoir in the 1930s, when a prolonged period of hot weather occurs, the water level can sink to such an extent that it’s possible to walk among its ghostly remains. During drought, the remnants of Mardale Green, including dry stone walls and an old bridge, can become visible.

Derwent and Ashopton

Ladybower Reservoir is a well-known tourist spot to those familiar with the Peak District. The picturesque man-made lake was built in the Upper Derwent Valley between 1935 and 1943 – the largest in the UK at the time.

But the reservoir’s construction came at a great cost to the bustling villages of Ashopton and neighbouring Derwent. Both villages, nestled high in the Peak District, were lost forever when they were demolished in 1943 and drowned to provide clean water across the East Midlands as part of the Derwent Valley scheme.

The decision, imposed by the Derwent Valley Water Board, outraged locals. Despite their protests, the villagers were relocated and rehoused in the nearby village of Bamford.

The homes in the village of Ashopton(Image: Derby Telegraph)

The homes in the village of Ashopton(Image: Derby Telegraph)

Bodies were exhumed from graveyards, and a local church held its final service. The buildings that once made up these thriving villages were reduced to rubble.

As the dam filled, the crumbling ruins disappeared beneath millions of gallons of water, never to see the light of day again. All that remained was an untouched spire from the church of St John and St James, kept as a memorial for Derwent villagers.

It poked out of the water for over a year, posing as a haunting reminder of what once was. But when that too was demolished and vanished beneath the sheet of blue, no memory was left of the lost villages.

That was until heatwaves hit the country in 1976, 1989, 1995, 2003 and 2018. Low water levels meant the villages emerged in a rare occurrence, offering visitors an eerie glimpse into its past.

During dry spells, a walk around the village community can still find signs of life beneath the water, including cottage doorways, walls, hearths, pump houses and bricks.

Greenbooth The old Lodge Dam to Greenbooth Village(Image: Photo © James Brownbridge (cc-by-sa/2.0))

The old Lodge Dam to Greenbooth Village(Image: Photo © James Brownbridge (cc-by-sa/2.0))

Six decades later, those who lived there are still haunted by memories of how the historic Norden village of Greenbooth became submerged under millions of gallons of water. After four years of construction, it was flooded in the early 1960s to create the last in a series of four reservoirs in the Naden Valley.

Today, Greenbooth Reservoir is an essential part of the beautiful countryside north of Heywood, visited by dog walkers, hikers, and nature lovers. A handful of eyewitnesses to the times still well remember the story of how the Heywood and Middleton Water Board’s proposals to flood the Naden Valley in the mid-1950s sounded the death knell for a declining village.

Greenbooth’s population had been shrinking for decades before the decision to flood it. A ‘throwback to the 19th century’, it had been built around the local mill, and never had any electricity.

When James Butterworth established a weaving mill in the area in the 1840s, it was known as Green Booth. Fed by local coal, it produced woollen flannel for clothing manufacturers across the north of England.

While it seems quaint and bucolic now, the ‘new’ village Butterworth established—which became known by the single word Greenbooth—was cutting-edge for the time. With rows of terraces, a little school, and bigger homes for managerial staff, Butterworth provided accommodation and a community for his workers, with rent and milk money deducted straight from their wages.

However, the 19th-century village of Greenbooth had no church or pub, and by 1911, it had lost its heart.

Plans to submerge the valley it sat in were confirmed in 1955, and the village was finally empty not long after. When it was demolished, 46 houses, 20 of which were derelict, remained in the village.

The 40 metres high and 300 metres long reservoir was completed in 1963 and officially opened in August 1965.

Watergrove A very dry Watergrove Reservoir(Image: MEN)

A very dry Watergrove Reservoir(Image: MEN)

In the 1920s, to solve Rochdale’s desperate shortage of drinking water, the council decided to build a reservoir by flooding the valley north of Wardle, where the village of Watergrove had existed for nearly 700 years.

By the first half of the 19th century, it was a thriving community. Its coal was in great demand as the Industrial Revolution gathered pace, but it was cotton that really brought people to the village.

The Watergrove United Free Methodist Church was built in 1852, and its baptismal register showed 616 births between 1854 and 1933. However, by the depression in the 1920s, the population had dropped to below 200.

Meanwhile, Rochdale’s drinking water situation was becoming precarious. In 1920, the town was buying 300,000 gallons of water a day from Bacup, and during the 1934 drought, it was buying more than one million gallons a day from Oldham.

Parliament approved Rochdale Council’s application to build a reservoir at Watergrove, and work began in June 1930. Some villagers resented the decision, and one wrote in Lancashire dialect to the chief engineer at Watergrove, saying people should use less water.

On the fascinating Abandoned Communites website, several photographs show remnants of the village that have resurfaced in times of drought.

Today, the area is a popular destination for watersports, horse riding, orienteering, walking and family day trips.