By Trevor Fairbrother

Quibbles aside, this book’s profusion of illustrations is a windfall for artists, art students, and those keen on close looking and visual culture.

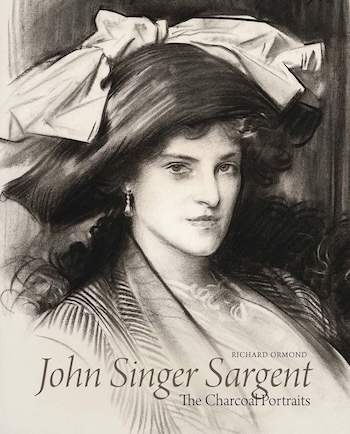

Book cover with detail of Lady Anne Innes-Ker (1911; private collection)

Entries on 694 drawings constitute the bulk of Richard Ormond’s new book John Singer Sargent: The Charcoal Portraits (Yale University Press, 407 pages, $80). In the words of the publisher, these works “capture the essence of British and American high society in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, portraying an elite clientele that includes aristocracy, royalty, politicians, artists, writers, actors, financiers, and philanthropists.” In his “Introduction,” Ormond outlines the artist’s studio practices and evolving stylistic interests. He also reviews period approaches to framing and explains why some works have yellowed over time.

Sargent typically finished a charcoal in one session lasting two to three hours. This differed drastically from the marathon of sittings necessary for a large oil portrait. He preferred a sheet of French handmade paper measuring approximately 24 by 18 inches. Most subjects face the viewer or present a slightly turned head. The image is slightly less than life-size. There were two options for the background: the empty brightness of the unmarked paper or bold strokes of charcoal that evoke shadowed space.

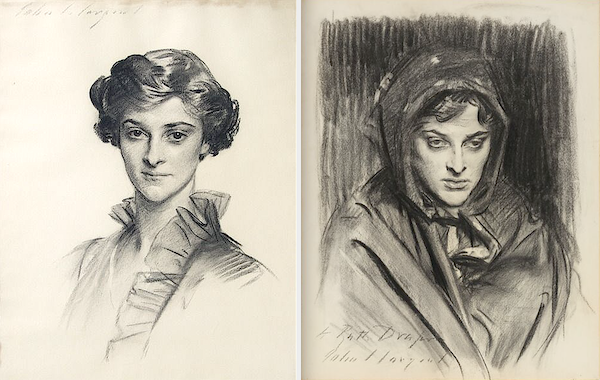

The artist’s trademark virtuosity is evident in the portrait on the book jacket, Lady Anne Innes-Ker heavy black-on-black marks for the hair and the darkest areas; rapid confident lines for the striped textile; the faintest touches for the light tones of the face and the bow atop the hat; and crisp, gleaming highlights on the earring and blouse, produced by the scrupulous erasure of charcoal. Two portraits of actress Ruth Draper offer a comparison of these different background treatments. These drawings also show Sargent responding to the same person in very different scenarios. The first depicts Draper – a pert, quick-witted New Yorker – as one might encounter her at a social gathering. The second shows her in costume, impersonating an impoverished immigrant searching for her injured husband in a Manhattan hospital.

Flattery and fiction creep into professional portraiture because a client is paying for a service. The artist may try to dictate the costume and pose, or the sitter may prove demanding about the likeness. In short, the ambience of their brief time together is pivotal. How truthful, then, are the portraits Sargent made on commission? Someone’s external appearance is conjured on canvas or paper, but each viewer will read the image subjectively, intuiting the character the sitter may have tried to present and grasping what the artist chose to picture.

A telling anecdote is connected with the charcoal of the Bostonian William Lawrence. When donating it to a museum in 1975, the subject’s son expressed disdain for Sargent’s delineation of a “cold, urbane” bishop: “No one who ever knew and loved my father has ever liked the picture.” Hugo Francis Charteris posed for his charcoal in a jacket and bow-tie, which the artist drew but then erased at the last minute in favor of an invented overcoat and evening scarf. Sargent insisted that his alteration improved the composition, and Charteris grudgingly accepted his fate: “I look cynical, sly, severe, but very spry and alert.” If the young aristocrat had not written those comments in a family letter, we would believe that the artist’s image was true. And what about the work on the cover of this book? Did Sargent’s rendering of the young American’s stiff and cool demeanor hint at a calculating aplomb or emotional hardness? What did he feel as he drew her?

Ruth Draper (1913; private collection) and Ruth Draper in the Character of a Dalmatian Peasant (1914; Museum of the City of New York)

Ormond is apt to oversimplify the artist’s biography in The Charcoal Portraits. He says that Sargent “shut up shop” as a portrait painter in 1907 and made a “switch of careers” in favor of a large mural scheme destined for the Boston Public Library. He bases the claim on a letter in which the artist ridiculed his charcoals as “mugs” and his oil paintings as “paughtraits” and declared himself sick of both lines of work. But the much-quoted phrase “No more paughtraits” was surely an empty promise Sargent coined to amuse Ralph Curtis, the dear old friend who received the letter. In truth, his portrait shop remained open: he tried (with moderate success) to make fewer paintings while concurrently increasing his output of charcoals.

Sargent’s ability to visualize individual character, social standing, and profession merits applause in the “Introduction.” Ormond feels that the charcoals of aristocrats stand out from those that depict artists and intellectuals because the artist had an eye for “the marks of high breeding.” The author’s personal connections to Sargent and the Edwardian ruling class may have sharpened his opinions. His maternal grandfather was Sir Alexander Doran Gibbons of Stanwell Place, Middlesex. His paternal grandmother was Violet Sargent, the artist’s younger sister, who married the scion of a wealthy Swiss business family, Francis Ormond. In 2001, Queen Elizabeth II appointed him a Commander of the Order of the British Empire (“For Services to Museums”).

It is disheartening that Ormond overlooks the fact that the artist never married, rarely acknowledging sitters who were part of a sexual minority. I found exceptions in the entries on two drawings: Olga, Baroness de Meyer (“said to have been bisexual”) and Robert Gould Shaw III (“troubled by his homosexuality, for which he spent time in prison”). The topic of sexual orientation is relevant because Sargent’s social status amongst Britain’s ruling class was diminished on two scores: he was an American interloper, and he was a bachelor. His London career began at the moment when the government made homosexual behavior illegal. He fostered inscrutability by monitoring his public persona and guarding his private life. One advantage he possessed was to be characterized in the press as a daunting, masculine figure: he was bearded, corpulent, and very tall.

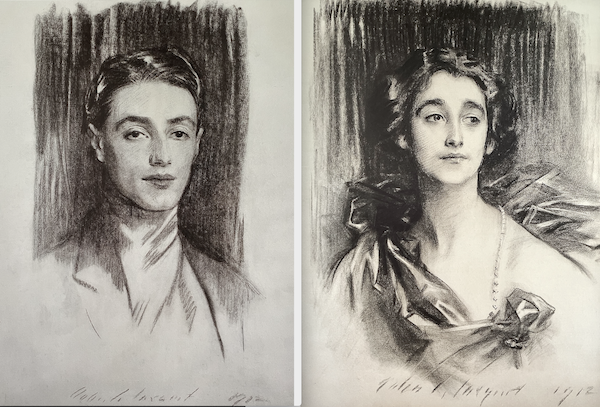

Sir Philip Sassoon, Bt (1912; Houghton Hall, Norfolk) and Sybil Sassoon (1912; private collection)

Sitters of Jewish ancestry or background are seldom identified in this book. Two exceptions are Boston rabbi Charles Fleischer and London pianist Myra Hess. Sir Philip Sassoon was both a Jew and a closeted homosexual, and Ormond relies on euphemisms to suggest those facts. Thus, Sargent admired the man’s “dark good looks and stylish, insouciant personality;” Sassoon was “an aesthete of great sensibility” and a person who “decorated his houses with exquisite taste.” And he “made a name for himself as a social host,” but his bachelor status goes unstated. The catalogue entry on the portrait of Philip’s sister Sybil declares: “Sargent was fascinated by the Sassoon family, with their exotic looks, elegance, vitality and taste.”

Socializing with the Sassoon siblings and the family of Asher and Flora Wertheimer gave Sargent much pleasure. The bonds between him and his Jewish patrons may have been strengthened by their individual experiences as outsiders. After the First World War, the artist witnessed an upsurge in British antisemitism and anti-immigration campaigns. In 1923, nine of his paintings of the Wertheimer family arrived at London’s National Gallery at the bequest of Asher Wertheimer. A ruckus ensued; Parliament debated the donor’s wish that the ensemble be hung permanently in one gallery. One malicious politician dismissed them as “clever, but extremely repulsive, pictures” that would constitute “a chamber of horrors.” (For the record, in her 2024 book Family Romance: Sargent and the Wertheimers, Jean Strouse compiled a list of the artist’s Jewish sitters.)

In 1926, London’s Royal Academy hung more than 60 Sargent charcoals in its massive memorial exhibition.

The scholarly apparatus for each item in the “Catalogue” consists of an image, physical data, provenance, and a brief descriptive text with an emphasis on lineage, marriage, and professional distinctions. The drawings are listed alphabetically by sitter. From an art-historical perspective, I would have arranged the entries chronologically. That tactic would have allowed one to parse the sequence of images for stylistic shifts and to consider the different batches that Sargent produced during various working visits to the U.S. (About a third of these portraits depict Americans.)

The “Catalogue” contains several drawings that do not conform to Sargent’s usual formula for commissioned charcoals. Some are smaller in size. One is a quick impression of an interior with a man whose identity “is not certain.” Two are deathbed portraits, including King Edward VII. Some are studies rather than formal portraits. The latter group includes a head of Olimpio Fusco, a man likely hired as a model for the mural work. Sargent did not sign the sheet, but he recorded the subject’s name and street address. This work remained in the artist’s personal collection along with a few analogous sketches inscribed with names and London addresses, which are excluded from The Charcoal Portraits excludes: one fine example shows Beatrice Stuart.

Quibbles aside, this book’s profusion of illustrations is a windfall for artists, art students, and those keen on close looking and visual culture. The publication also opens a window on a historical period. Someone embarking on a costume drama set in the rarefied social landscapes of Sargent’s realm could not ask for a better primer.

Trevor Fairbrother is a curator and writer. He illustrated numerous examples of the charcoals in Sargent Portrait Drawings, an inexpensive book from Dover Publications that has been in print since 1983. His latest contributions to the Sargent merry-go-round are an essay and interview that supplement Donald Platt’s Tender Voyeur, a collection of poems that meditate on the lush and sensual aspects of Sargent’s work. Tender Voyeur is published by Grid Books.