Tyler Mischley, 38, has lived with opioid use disorder (OUD) since he was 15. At age 18, he got an additional diagnosis of chronic pain—doctors discovered that the source of his back pain was half an extra intervertebral disk at the bottom of his spine, pinching his S1 nerve. It’s inoperable.

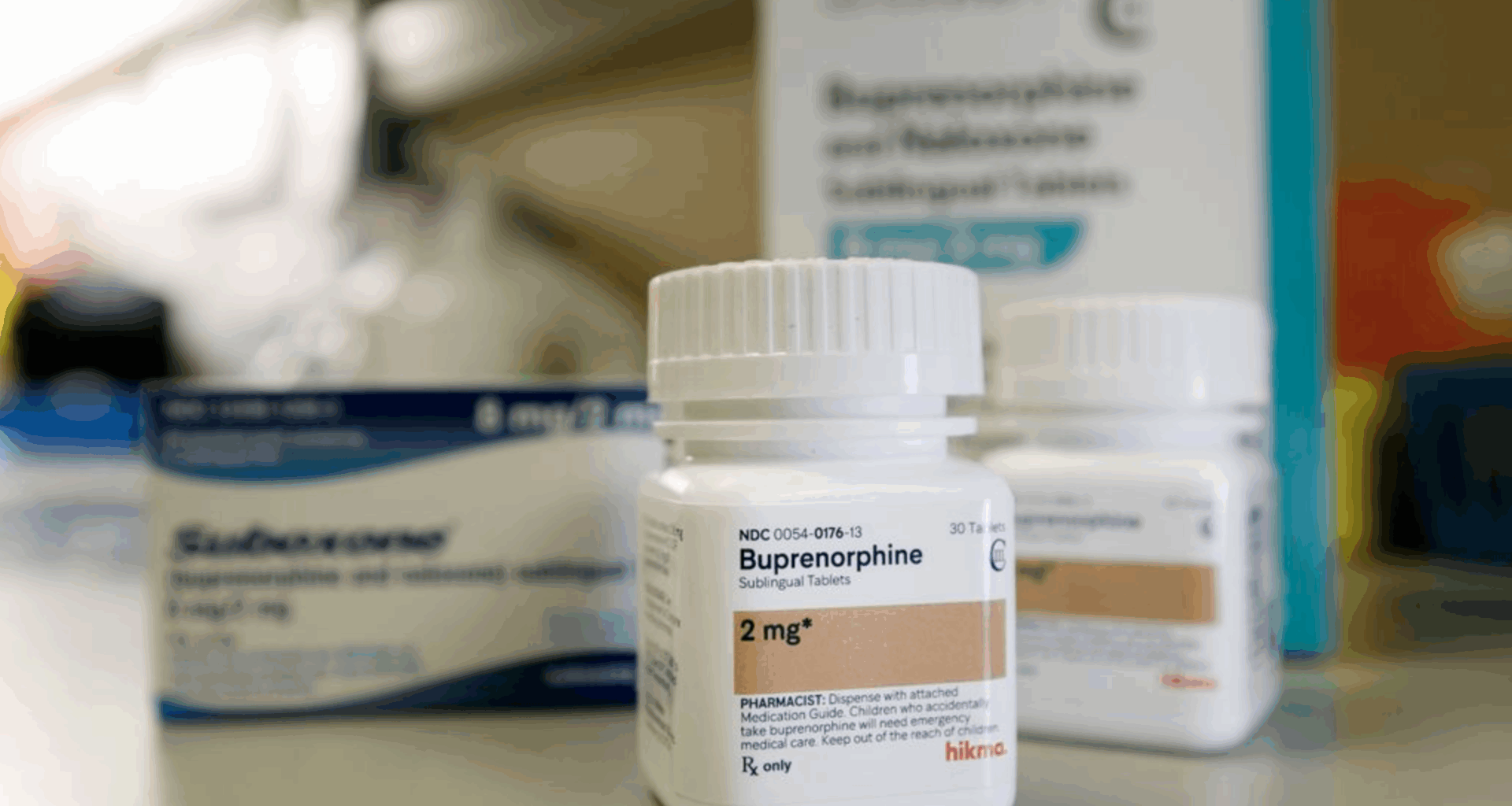

In 2005, Mischley became one of the first people in his Michigan county to be prescribed buprenorphine for OUD. Buprenorphine has been a Food and Drug Administration-approved pain medication since the 1980s, but was only approved as a medication for opioid use disorder (MOUD) in 2002. Tighter regulations wouldn’t arrive until later, and Mischley’s initial prescription was for 64 mg—a dose that would be unheard of today.

Mischley was on his mom’s health insurance plan, which was a good one because she had a government job with the United States Postal Service. Even that didn’t cover the entire prescription, leaving him with $200 or $300 in out-of-pocket costs each month.

“I told them that was too much, the cost was too much,” he said. “Everything was too much.”

But within a year his prescription was dropped to 32 mg, and things got easier for a little while.

Buprenorphine is a partial opioid agonist. It doesn’t affect people as strongly as full agonists such as methadone, which has been an FDA-approved MOUD for over 50 years, or unregulated opioids like heroin and fentanyl. Buprenorphine dulls the effects of full agonists, but on its own it can be enough to keep withdrawal at bay, which is all many OUD patients are looking for. And unlike methadone, which can only be dispensed at a clinic, buprenorphine can be picked up at a pharmacy like any other prescription.

Mischley still had access to street-supply opioids that more readily produced a high, and found this challenging since he wanted to avoid them. But with a 32-mg buprenorphine prescription he managed to make things work by waking at the crack of dawn, taking two of his four daily pills and then falling back asleep. By the time he woke up again to actually start his day, the medication would have kicked in and would make other opioids feel like nothing if he took them. Which he found helpful.

“If I went and shot heroin after using Suboxone, it wouldn’t do anything,” he said. “It would just be like injecting water.”

The two MOUD tablets that the FDA approved in 2002 were Subutex, the brand name for buprenorphine, and Suboxone, which contains both buprenorphine and a smaller amount of naloxone. The Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) endorsed the new MOUD up to 32 mg per day, which clinical evidence strongly supported as the maximum dose. The FDA, however, sent them onto the market with the following labeling:

The recommended target dose of SUBOXONE is 16 mg/day. Clinical studies have shown that 16mg of SUBUTEX or SUBOXONE is a clinically effective dose compared with placebo and indicate that doses as low as 12 mg may be effective in some patients. The dosage of SUBOXONE should be progressively adjusted in increments / decrements of 2 mg or 4 mg to а level that holds the patient in treatment and suppresses opioid withdrawal effects. This is likely to be in the range of 4 mg to 24 mg per day depending on the individual.

Over the next two decades, the impact of this would be that insurers generally won’t cover anything higher than 24 mg, and most prescribers won’t push them because they won’t consider higher doses in the first place.

But for many OUD patients, higher doses are what make buprenorphine effective.

Buprenorphine prescriptions above 24 mg have been linked to higher treatment retention, including in the period immediately after initiation. They’ve also been linked to a 50-percent reduction in emergency department visits and inpatient care. And over the past decade as fentanyl has taken the place of heroin in the unregulated drug supply, opioid tolerances are increasing and more people are finding that a maximum dose of 16 mg or 24 mg isn’t enough to keep them well.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention data for 2023

For those patients, the options for avoiding withdrawal are generally street-supply opioids, or methadone.

Health care providers who prescribe opioids for pain management use a framework called morphine milligram equivalents, or MME, to calculate what a patient’s dose for one opioid would correspond to for a different opioid. This doesn’t apply to MOUD, for a laundry list of pharmacological reasons starting with the fact that buprenorphine is a partial agonist and methadone is a full agonist; it’s a little like comparing apples to oranges. There is no universal equation that can say exactly what 24 mg or 32 mg of buprenorphine translates to in methadone. But for anyone taking more than 8 mg buprenorphine, standard practice would be to make the switch by abstaining for 24 hours, then starting with 30 mg methadone and going up from there.

Both methadone and buprenorphine are invaluable MOUD, but they are very different. Not everyone wants to go from a partial agonist to a full agonist, and vice versa. But the biggest reason someone struggling on a high dose of buprenorphine wouldn’t want to switch to methadone isn’t because of the medication itself, but because of the clinic system. Getting methadone for OUD usually means reporting to an opioid treatment program at dawn daily. Everything else in life—work, travel, illness—has to fit around that. Add to that the heavy surveillance, lack of privacy, long commutes for people in rural areas and notoriously punitive clinic culture, and it’s clear why for many people the biggest advantage of buprenorphine is that it can be discreetly picked up once a month at a pharmacy.

Capping medication at a dose that doesn’t provide adequate relief is what pushes many patients to street supply, which is more dangerous than pharmaceuticals but easier and often more dignified to access. Research on extended-release injectable buprenorphine suggests that for people who inject opioids, doses higher than 32 mg could result in less use of street supply—if insurance weren’t a barrier.

In 2010 the FDA doubled down following its approval of Suboxone film (which has become the more recognizable formulation, compared to the tablets) stating that doses higher than 24 mg “have not been demonstrated to provide any clinical advantage.”

As part of the approval process, manufacturer Reckitt Benckiser Pharmaceuticals Inc stated that anything above 16 mg should be considered an exception.

“[T]here should be little difference in clinical effectiveness at doses between 16 mg and 24 mg in most patients,” Reckitt Benckiser advised. “When a patient expresses a need for a higher dose, consider the possible causes [and first] explore other alternatives. Also consider the possibility that the patient may be exaggerating symptoms to obtain additional medication for diversion.”

There has been no watershed moment for access to doses above 24 mg or even 16 mg—but there has been some progress.

Pre-pandemic data show that only around 3 percent of buprenorphine prescriptions were for doses above 24 mg, and only around 4 percent of prescribers were writing them.

“A lot of physicians and nurse practitioners have been afraid to write [prescriptions] for higher doses,” Dr. Edwin Chapman, an internal and addiction medicine specialist who has been treating OUD patients for 25 years, told Filter. “In their training, they were told for years that 16 mg was the target dose, 24 mg in special cases.”

Patients and providers have been advocating for years to remove the additional layers of bureaucracy and surveillance that come with prescribing buprenorphine for OUD, like urine drug screens and extra steps required for insurance approval. In 2023, the Drug Enforcement Administration eliminated the X-waiver, a federal requirement that had been created specifically for buprenorphine and had severely restricted access to prescriptions. Telehealth prescribing has also now been expanded, building on momentum that began during the COVID-19 pandemic. There has been no watershed moment for access to doses above 24 mg or even 16 mg—but there has been some progress.

In 2023, Chapman and dozens of other stakeholders presented the FDA with their case for doses over 24 mg having benefits for many patients, at no added risk. The concept gained traction with federal agencies, and in December 2024 the FDA made a public recommendation that manufacturers of buprenorphine products that dissolve under the tongue (meaning tablets or film, but not the longer-acting injectable formulations) update their labeling.

“[N]either 16 mg/day nor 24 mg/day should be interpreted as maximum dosages,” the FDA stated.

The agency advised removing references to a “target dose,” and noting that doses above 24 mg “have not been investigated in randomized clinical trials but may be appropriate for some patients.”

In a letter explaining the decision to prescribers, Dr. Marta Sokolowska of the FDA’s Center for Drug Evaluation and Research noted that the agency was aware that insurers had been restricting access to higher doses as a consequence of the language previously used on the labeling.

In 2023, one of Chapman’s patients overdosed after United Healthcare capped his buprenorphine coverage at 24 mg. The patient survived—and the story made the front page of the Washington Post. Since then, United has covered Chapman’s patients up to 32 mg without issue. But he still has to go through the process of obtaining prior authorizations. And months after the FDA formally clarified that buprenorphine has no maximum dosage restrictions, this hasn’t changed.

“8-2MG” refers to a standard Suboxone strip containing 8 mg buprenorphine combined with 2 mg naloxone. Insurers will often cover prescriptions up to three strips (24 mg buprenorphine) per day, but not four.

“I don’t know if it’s just because of me or whether other doctors have difficulty getting above 24 mg with United Healthcare,” Chapman said. “But the point is they’re still saying 24 mg [is the limit].”

Like every other extra bureaucratic hurdle attached to buprenorphine, prior authorizations are associated with decreases in treatment retention.

The American Medical Association, one of the organizations that pushed the FDA to revise its labeling recommendation, has urged insurers to update their policies accordingly. The FDA is also currently supporting a high-dose buprenorphine study in collaboration with the Department of Veterans Affairs. But experts reached by Filter say it could be a year or more before the FDA recommendations begin to have real-world impact for most patients. Meanwhile, many will lose access amid the arrival of President Donald Trump’s “big, beautiful law” and its $1 trillion in cuts to Medicaid. Of the nearly 2.5 million people in the United States who filled buprenorphine prescriptions between April 2020 and March 2024, approximately 48 percent used Medicaid to do so at least once.

Elimination of the X-waiver has not yet done much to actually increase the number of health care providers prescribing buprenorphine. And, despite the updated labeling recommendations and the removal of the X-waiver, some states also maintain their own restrictions that impede access.

“I’ve had people tell me not even to send the second prescription because they know they can’t afford it this month.”

Dr. Jared Matthews, an addiction medicine physician in Tennessee, described the state as “a really great example of what not to do.”

Tennessee has taken some recent steps to increase access to 24 mg doses of buprenorphine, but in practice the state effectively caps prescriptions at 16 mg.

“Administrators with the actual Medicaid program, most of their higher-level executives are physicians,” Matthews told Filter. “They are well aware of what the medical evidence tells them they should be doing … yet when they take these proposals to their political leadership, the answer is always No.”

So for patients who require a higher dose, Matthews writes two separate prescriptions: one for a 16 mg dose covered by Medicaid, and one for whatever remaining number of milligrams the patient needs, which they must pay for out of pocket. Each additional 8 mg can cost upwards of $200 per month.

“I probably have no less than 100 patients where 16 milligrams is not adequate to control the signs and symptoms of their opioid use disorder,” Matthews said. “I’ve had people tell me not even to send the second prescription because they know they can’t afford it this month.”

In Kentucky, prescribing over 16 mg is restricted to advanced practice registered nurses certified in addiction medicine. The state also doesn’t allow buprenorphine to be prescribed for pain management, only OUD.

“Indiana allows it for pain management,” Dr. James Murphy, whose clinic straddles the border between the two states, told Filter. “Federally, it’s allowed. The Veterans’ Affairs nationally actually has Suboxone listed as one of the choices that we can use for chronic pain management. Yet in Kentucky that would be considered illegal.”

Murphy treats some pain patients with buprenorphine, or with methadone; many have complex needs wherein OUD and chronic pain overlap. As a result of the outdated regulations, he fields a lot of calls from pharmacies and insurers alleging that his patients’ doses are too high. But for his patients across the river in Indiana, he’s able to more readily prescribe the doses they need.

“What is it about a river or a line or a border that makes the patient different?” Murphy asked. “The patient with chronic pain and opioid use disorder is the same in Kentucky as [in] Indiana.”

“Red flags” are triggered by activity the DEA considers suspicious.

Buprenorphine is regulated under Schedule III of the Controlled Substances Act. As with other opioid analgesics, and certain other pharmaceuticals like benzodiazepines, buprenorphine prescriptions are tracked by the DEA through a nebulous web of proprietary algorithms known as prescription drug monitoring programs (PDMP). “Red flags” are triggered by activity the DEA considers suspicious.

Providers, for example, can trigger red flags by writing a lot of prescriptions for higher doses. Pharmacists are required to check for these red flags, and can be held liable for filling prescriptions the DEA determines they shouldn’t have.

Patients, meanwhile, can get red-flagged by paying for prescriptions in cash—which data suggest is the most common method of payment for buprenorphine prescriptions above 24 mg.

“Sometimes it’s difficult for patients to even fill a buprenorphine script,” said Jonathan Larsen, a public health law expert at Temple University. “If a pharmacist is feeling uncomfortable about [dispensing] buprenorphine because it might raise red flags.”

A secret shopper study conducted in 2022 found that in Tennessee, the majority of pharmacies would likely refuse someone trying to start treatment with buprenorphine. Researchers called 183 pharmacies, across all but one of the state’s 95 counties, asking to fill a prescription for a new patient—and 53 percent of the pharmacies said No. Many had caps on the number of buprenorphine patients they were allowed to serve, as well as waiting lists for when space opened up. Many pharmacies didn’t stock buprenorphine at all, citing pharmacist discretion as one of the main reasons.

Murphy has written prescriptions that patients were unable to pick up because pharmacists refused to fill them. This is a widespread barrier. Fear of being raided and shut down keeps many pharmacists from filling higher-dose buprenorphine prescriptions, even if the insurer has agreed to cover it.

One doctor stopped seeing Mischley after a urine drug screen indicated he’d used marijuana.

These days, Mischley’s prescription is for 24 mg and that’s been working well for him. But over the past two decades, heavy surveillance and aura of illegality around higher-dose buprenorphine has cut off access to his prescription multiple times.

One doctor stopped seeing him after a urine drug screen indicated he’d used marijuana. This was before both medical and adult-use legalization in Michigan, but this didn’t seem to be where the concern was coming from.

“[The doctor] said since his license was federal,” Mischley said, “and [marijuana was] illegal federally, he couldn’t risk that.”

Around 2012, the doctor prescribing Mischley’s buprenorphine by that time was investigated by the DEA, and his practice subsequently shut down. This doctor also issued medical marijuana cards, and apparently the DEA felt he issued too many of them.

Mischley is on his seventh provider. Like paying in cash, frequently changing doctors can be a DEA red flag, too.

Top image (cropped) via Drug Enforcement Administration. First inset graphic via Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Second and third inset graphics via Dr. Edwin Chapman.

R Street Institute supported the production of this article through a restricted grant to The Influence Foundation, which operates Filter. Filter‘s Editorial Independence Policy applies.