(Credits: Far Out / Cash Box / Columbia)

Thu 14 August 2025 22:30, UK

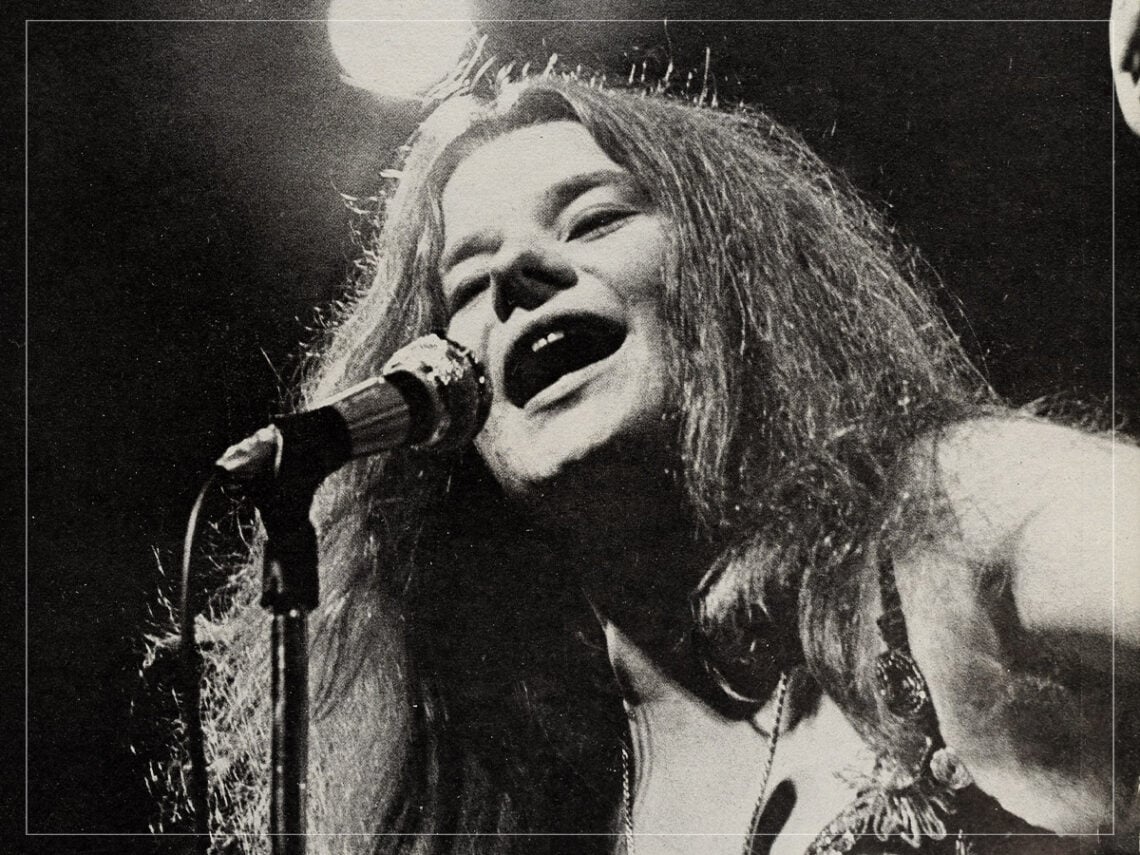

It’s easy to make a case for Janis Joplin being one of the most tortured poets in all of history.

More than just a conduit for her own pain, Joplin was her pain, the cracks in her voice merely a surface signifier of everything she felt deep in her bones. Even some of her more joyful endeavours always came back to the one thing she defined life by: loneliness. It’s a fairly common theme in blues-inspired music to talk about resigning yourself to a life of solitude and bitterness, even in moments when laughter and happiness become a welcome distraction.

However, those experiences are also often what solidify such attitudes. Joplin, through her music and songwriting, frequently talked about love and romance as though the good parts are always fleeting, as though the permanence of happiness is a luxury that would never be woven into her own story, left out of her heart and soul and given to other people to enjoy and cherish. We hear about the so-called troubled artisté in almost every corner of culture today, but Joplin, unlike many, really, truly knew all about misery.

Strangely, it’s also the biggest and most sobering reason why almost every peer from that San Fran 1960s scene had some quasi-mythologised, romantic story about her, even the ones where her turmoil painted the lines of her words and expressions like something she was born from. Like she’d been created by some unnamed, faceless divine figure, grown from the greens and browns of turmoil itself, and put on earth to generate art that made even the most established of players sit up straight and listen.

Or gawk, in the case of Peter Albin. But Joplin wasn’t the source of anyone’s desires, not traditionally, but rather this strange, otherworldly entity that appeared roughened and sharpened by some sort of trauma she carried in her posture and the clothes she wore – white, open-chested T-shirts and a look that just glared in provocation. Every person with eyes and half a mind to read between the lines would know that most of this came from being a woman surrounded by men, but blues, according to John Kay, became her “protective shield”.

Most people think of Joplin with sadness, because that, above all, is everything her art came from. Most people see her as a tragic figure because, when all’s said and done, that’s precisely what she was. But perhaps the most tragic part of all of this, beyond the intricate reasons why she was the way she was and why she, in the end, succumbed to the one thing that destroyed her all along, is that she saw it too. Countless others described her with pitying words like sad, empathetic sighs, but she saw it too. She saw herself exactly the same way.

“I can’t write a song unless I’m really traumatic, emotional, and I’ve gone through a few changes, I’m very down,” she once told Rolling Stone. “No one’s ever gonna love you any better, and no one’s gonna love you right.” The song she’d been addressing, and perhaps one of her most tragic, was ‘Kozmic Blues’, the song that she once said, “Just means that no matter what you do, man, you get shot down anyway.”

This solemn detachment, or resignation – the familiar Joplin kind – is felt throughout the song, in the way her words beat to the rhythm of her own inherent disillusionment and belief in the fact that, no matter what she does, her fate is sealed, and her destiny is one filled with loneliness and despair. As she sings, “I said you, they’re always gonna hurt you / I said they’re always gonna let you down”, while ruminating on how she’s always moving, though she doesn’t know why, because there’s no point when the end destination doesn’t even exist.

Related Topics