VJ Day 80 years on: ‘Despair, illness, no hope, no idea of when this war was going to end’ (Image: Anne Durbin and Liz Rowbotham)

(Image: Anne Durbin and Liz Rowbotham)

‘Despair, illness, no hope — no idea of when this war was going to end. Apparently forgotten by our friends.”

The haunting words of a Greater Manchester soldier who was held as a prisoner of war in Thailand and forced to work on the infamous Thailand to Burma ‘Death Railway’, immortalised in the 1957 war film The Bridge on the River Kwai.

Maurice Naylor, a Manchester University graduate who was born in Flixton, Trafford, was 24 when he was held captive by the Japanese in the Far East.

And for Maurice, and many thousands like him, every morning began exactly the same way — for three long years. He was lucky to survive. Many didn’t — losing their lives to rampant disease and illness, brutal beatings and the unthinkable conditions ‘working’ on the railway’s construction.

Never miss a story with the MEN’s daily Catch Up newsletter – get it in your inbox by signing up here

Before Maurice passed away at the age of 99 in 2020, he recorded a series of audio interviews about his experiences, many of which were never broadcast. Now his voice — and his powerful story — is being heard once again to mark the 80th anniversary of VJ Day today, Friday, on the BBC’s The History Podcast: The Second Map.

Maurice was a gunner in the 18th Infantry Division deployed to Singapore when Japan invaded in 1942. He would be one of around 130,000 British, Indian, Malayan and Commonwealth soldiers to be taken by Japan as prisoners of war following the fall of Malaya and Singapore.

Maurice passed away aged 99 in 2020(Image: Anne Durbin and Liz Rowbotham)

Maurice passed away aged 99 in 2020(Image: Anne Durbin and Liz Rowbotham)

VE Day — Victory in Europe — was observed in the May of 1945, months before the surrender of the Imperial Japanese Army on August 15 after the dropping of the atomic bombs on Nagasaki and Hiroshima.

But the war wasn’t over for Maurice. He was held in captivity at a camp 1,000 miles away in Thailand — where he remained for three years.

“Somebody had seen a well-dressed Thai who’d said ‘war in Europe is over’, or something like that,” recalled Maurice. “You could believe it or not, just as you wanted.”

Maurice told how he was forced to work on the railway from 8am everyday on just a bowl of rice.

“If you could just try and imagine a typical day,” he said. “It was dawn just before 7am in the morning and we were woken by buglers. We’d be called out on roll call as it was getting light. Tenko was the Japanese word for roll call. We then had a meal, which consisted of rice and that was it.

“At 8am, we were sent out on working parties.”

Pictured, sixth from left, at a memorial in Singapore(Image: Anne Durbin and Liz Rowbotham)

Pictured, sixth from left, at a memorial in Singapore(Image: Anne Durbin and Liz Rowbotham)

Maurice was part of a punishing forced labour campaign working to build a bridge for trains to cross on the railway. He told of carrying timber up from riverbeds for years, alongside malnourished and ill comrades.

“I had chronic diarrhea most of the time when I was a prisoner but that wasn’t considered bad enough normally to stop me going out on a working party, although you might want to go to the toilet 10, 12, 20 times a day,” he said.

Thousands died due to the conditions. “I had to put up with that,” he said. “It was a nightmare. And if we didn’t do the work properly, then it was the Japanese guard — they’d just beat around the head and shout at you.

“Despair, illness, no hope, no idea of when this war was going to end. Apparently forgotten by our friends.”

Maurice told of the death of his closest friend at the camp — saying many PoWs simply gave up.

“He was very despondent,” he said. “And I think, probably, he just gave up. A lot of the prisoners just gave up and died.”

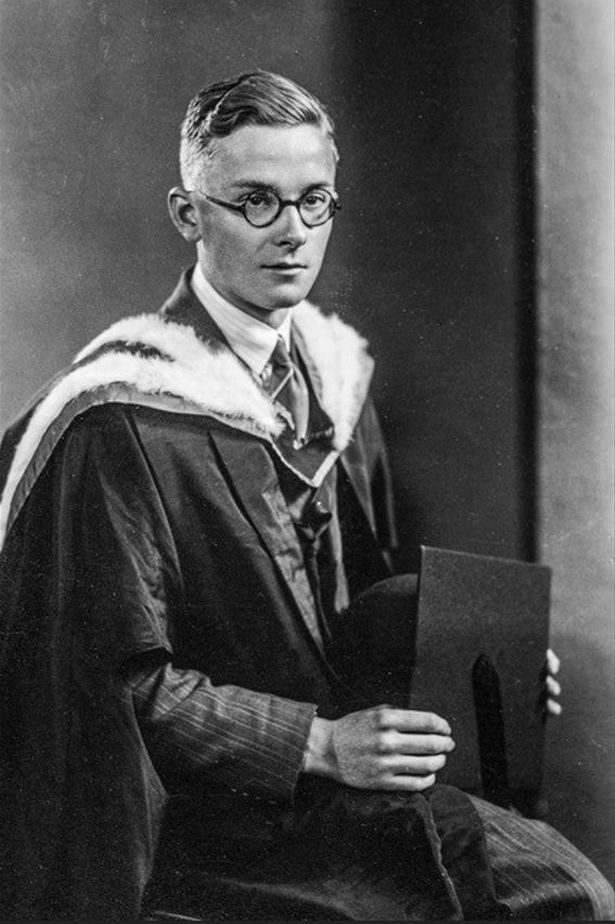

Pictured graduating from university in Manchester(Image: Anne Durbin and Liz Rowbotham)

Pictured graduating from university in Manchester(Image: Anne Durbin and Liz Rowbotham)

Join the Manchester Evening News WhatsApp group HERE

When Maurice eventually made it home, he weighed five-and-a-half stones. He returned to Liverpool on board the Orbita on November 9, 1945.

The father-of-three went on to hold senior executive positions with the NHS, both in Manchester and Yorkshire and was awarded a CBE for services to the NHS in 1973. After his retirement, he became the first director of the National Association of Health Authorities, serving in that role between 1981 and 1984.

He didn’t talk about what happened to him until he finally retired aged 61. Maurice’s daughter, Liz Rowbotham, told how her father returned to Thailand after the war.

She said: “He went back with his brother, who had been in the war, but in the European war. They went back with both their wives on a holiday to celebrate his retirement. I mean, he said he stood in the graveyard in Kanchanaburi, which is the nearest town to the bridge, and saw all these rows and rows of graves, and thought that he owed it to those men to tell the story of what had happened.”

The History Podcast: The Second Map is available to listen to on BBC Sounds from today – Friday.