The UK government’s proposed solution for long-term storage of high-level waste from the nuclear sector, a geological disposal facility (GDF), has been described as “unachievable” in a Treasury assessment of the project.

The National Infrastructure and Service Transformation Authority (Nista), a Treasury unit, made the assessment in its Nista Annual Report 2024-2025, published on 11 August, where it rated 213 other major infrastructure projects.

Some projects had their assessments redacted. AWE’s (the Atomic Weapons Establishment’s) Future Materials Campus was redacted on national security grounds, despite having received a public rating in the previous assessment published in January 2025.

GDF project so vast it requires two DCOs

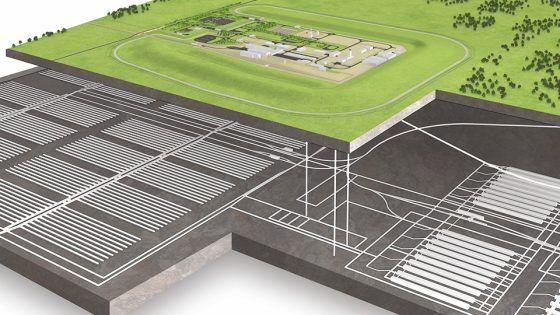

A GDF represents a monumental undertaking, consisting of an engineered vault placed between 200m and 1km underground, covering an area of approximately 1km2 on the surface.

This facility is designed to safely contain nuclear waste while allowing it to decay over thousands of years, thereby reducing its radioactivity and associated hazards.

NWS declares that this method offers the most secure solution for managing the UK’s nuclear waste, aimed at relieving future generations of the burden of storage.

The project would be so vast that it would require two separate development consent order (DCO) applications to be approved – one for exploratory works and another for the project itself.

GDF downgraded from having ‘significant issues’ to being ‘unachievable’

The IPA (Infrastructure Projects Authority) is one of two predecessor organisations to Nista – the other being the National Infrastructure Commission (NIC).

The 2025 Nista review is the first from the new organisation, but IPA previously produced similar reports on the Government Major Projects Portfolio (GMPP). IPA’s report published in January 2025 for the 2023/2024 period included an annual Delivery Confidence Assessment (DCA) for each project as far back as 2012/2013.

The GDF was rated Amber in 2013/2014 and the same again in 2023/2024, with a couple of fluctuations along the way; it was rated Amber/Red in 2017/2018 and went up to Green in 2020/2021.

Amber means: “Successful delivery appears feasible but significant issues already exist, requiring management attention. These appear resolvable at this stage and, if addressed promptly, should not present a cost/schedule overrun.”

The same definitions have been carried over to the new Nista report, which gave the GDF a Red DCA.

Red classification means: “Successful delivery of the project appears to be unachievable.

“There are major issues with project definition, schedule, budget, quality and/or benefits delivery, which at this stage do not appear to be manageable or resolvable. The project may need re-scoping and/or its overall viability reassessed.”

In addition, it lists the “whole life cost” as £20bn as a mid-range assessment, to £54bn as a high-end assessment.

Energy department says ‘progress continues to be made’ despite rating

The GDF project is the responsibility of Nuclear Waste Services (NWS) which is a subsidiary body of the Nuclear Decommissioning Authority (NDA).

The NDA is sponsored and funded by the Department for Energy, Security and Net Zero (DESNZ).

Responding to the rating, a DESNZ spokesperson said: “Constructing the UK’s first geological disposal facility will provide an internationally recognised safe and permanent disposal of the most hazardous radioactive waste.

“Progress continues to be made in areas taking part in the siting process for this multi-billion-pound facility, which would bring thousands of skilled jobs and economic growth to the local area.”

Anti-nuclear campaigner says Red rating ‘hardly surprising’

Nuclear Free Local Authorities secretary Richard Outram said: “The Nista Red rating is hardly surprising. The GDF process is fraught with uncertainties and the GDF ‘solution’ remains unproven and costly.

“A single facility as estimated by government sources could cost the taxpayer between £20bn and £54bn, this being a nuclear project it is much more likely to be the latter and beyond.”

Establishment of a GDF must have the agreement of the community which is to host it. Some communities that were being considered have withdrawn themselves from the process, most recently Theddlethorpe in East Lincolnshire, which leaves Mid Copeland and South Copeland as the only remaining possibilities being explored.

Outram went on to point out that, despite government policy on a GDF being focused on public acceptability and geological suitability, NWS was “forced to retreat from South Holderness and Theddlethorpe in the face of steadfast public opposition, and they were forced to withdraw from Allerdale because of unsuitable geology”.

He added that “NWS appears once again wedded to the pursuit of a site in either Mid or South Copeland” and that “resistance is growing in South Copeland and is not inconceivable that plans for a GDF in that area could also soon be shelved”.

“Now activists are lobbying county councillors to seek a proper debate and vote on continuing with the process,” he said.

“With delays inevitable, will HMG see repeated further slippage in the delivery timetable and a steady hike in costs. Unaffordability is cited as a specific risk in the report.”

Earlier this year, NWS chief of disposal safety Lucy Bailey wrote on NCE about why a GDF is the best solution for long-term storage of nuclear waste.

Like what you’ve read? To receive New Civil Engineer’s daily and weekly newsletters click here.