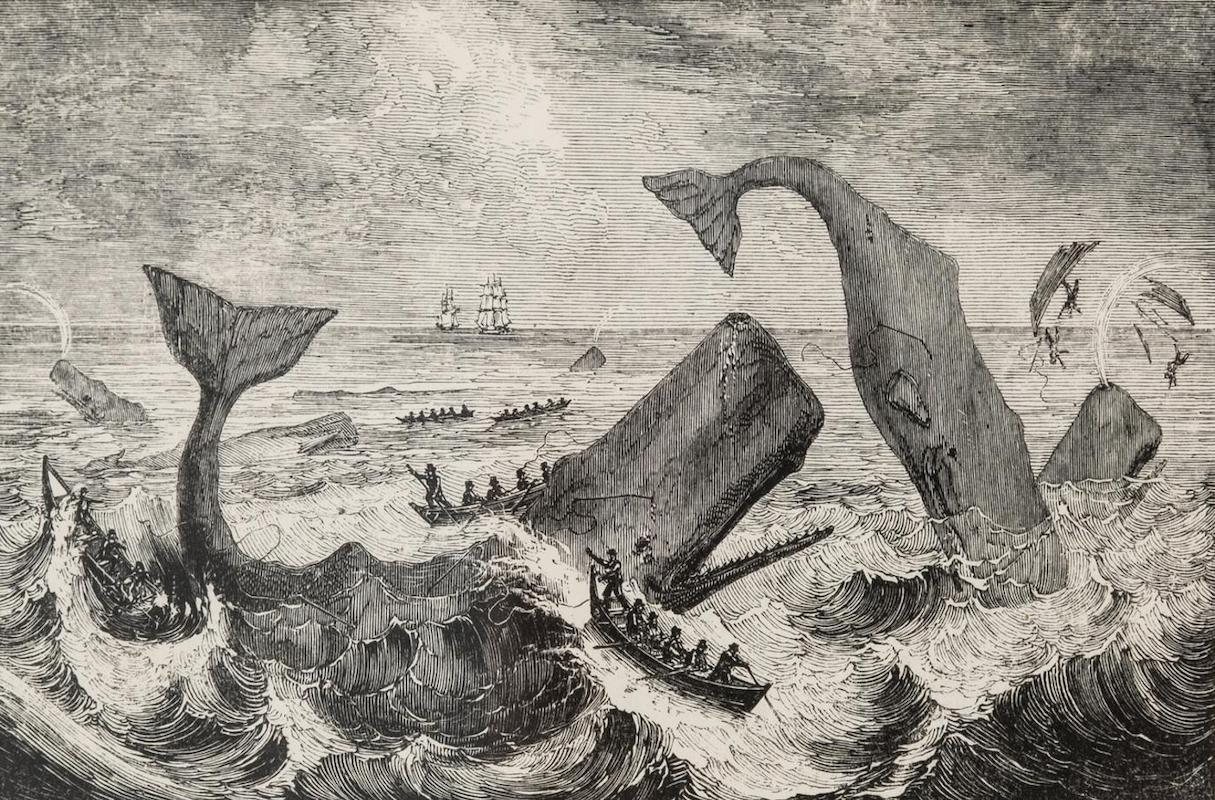

My summer of hiding out from the heat and watching cetacean documentaries continues, with a collection of films about sperm whales.

Moby-Dick is remarkably knowledgeable about the anatomy and behavior of the species, but Melville acknowledges that humans know very little about the sea or its creatures. It’s so vast and so diverse, and we can only see what rises to the surface. There are whole worlds below, that humans have never seen and, as of 1851, could never see.

Advances in technology in the twentieth century and into the twenty-first made it possible for the first time to dive down deep and learn the secrets of the sea. Among those secrets are those of the sperm whale.

This ocean giant, one of the largest animals that has ever lived and the largest toothed predator, was hunted almost to extinction for the oil in its enormous head. What that oil was, the whalers of Melville’s time didn’t know. They called it spermaceti and believed, for reasons not particularly clear to the modern mind, that it was actual sperm, as in spermatozoa.

That’s not what it is at all. It’s a complex organ that does two things. One it shares with other toothed whales including dolphins and orcas: it’s a mechanism for generating and processing sonar. The other is a bit more speculative; it’s believed that spermaceti contributes to the whale’s ability to dive deep in search of the giant squid that are the staple of its diet.

Spermaceti becomes more liquid the warmer it is. Scientists hypothesize that when the whale is on the surface, the contents of its head, which takes up a third of its body, are light and buoyant. But, as it descends into the near-freezing cold of the abyss, the waxy substance solidifies, becomes more dense and less buoyant, and allows the whale to dive down deep. Then when it’s ready to come up, the spermaceti warms and lightens, and back to the surface the whale goes. It’s thought that the whale can control this; that the process is voluntary.

What’s it doing down there, and how does it survive pressures hundreds of times stronger than at the surface? We have not, so far, seen the mythical battle of whale and giant squid. We know sperm whales eat squid: deceased whales’ stomachs are full of squid beaks, or squid bones as Melville called them, and round scars from squid tentacles are a common sight on whales’ bodies. In Ocean Giants: The Secret Lives of Sperm Whales, a young whale comes back from a hunt having overindulged, and he horks up a whale-belly-full of squid parts.

Comparative anatomist Joy Reidenberg has a theory. She notes that when whales have been fitted with trackers, they go down into the deeps, and as she puts it, they hang around there for a while, then come back up. They don’t seem to be pursuing anything. She proposes that they’re not pursuit predators, they’re lie-in-wait predators. They go down, they wait, the prey comes to them.

They do this, she thinks, with their teeth. Sperm-whale teeth and jaws are not designed for chewing. They’re not optimal for grabbing and holding, either, unlike orca or dolphin teeth: there aren’t any on the upper jaw, just on the lower. Maybe, she says, they’re actually meant to serve as lures, with some sort of bioluminescent mechanism, bacteria or whatever, that makes them glow in the dark.

She doesn’t produce any proof of this. It’s true that deep-sea organisms quite often do have some form of bioluminscence, and it is designed to attract prey into the predator’s jaws. If that’s what’s happening, it’s not as dramatic as the battle scenario, but if it works…

Another possibility is that whales are cruising along the bottom, using the lower jaw as a scoop. Still no epic battle, but plenty of food to fuel a body that, in maturity, ranges from 30 feet (10m) long in females to 50 feet (20m) in males. That body spends 80 to 90 percent of its life far below the surface, only coming up to breathe.

It eats in the water. It sleeps there, floating upright, usually in the company of its family and friends. It delivers its young there; a young calf has to stay close to the surface, and has to be protected and nurtured until it’s ready for the deep dive, but its mother will leave it in the care of another family member while she hunts.

We’re still finding out just how deep a sperm whale can go. Some sources say 10,000 (3000m). There’s proof that whales have gone down to 6000 feet (2000m).

How does an air-breathing mammal even survive in the uttermost darkness and crushing pressure? Let alone spend most of its time there, and do most of its hunting and feeding. Why doesn’t it implode?

The whale’s body has some incredible adaptations. I’ve mentioned sonar, and will say more about that in the next article. Here, what’s important is that a whale doesn’t need light to “see.” It can map its surroundings via echolocation, a sequence of clicks that resonate through the water and bounce back off objects and animals. The whale processes these echoes through the structures of its head, generating what amounts to series of images, a video as it were. It “sees” with sound.

A whale’s eyesight is pretty poor. A sperm whale has a narrow range of vision on either side, and can’t see behind or in front of itself at all. But its sonar can map everything around it, in absolute darkness.

Its body meanwhile is able to stay down for over an hour, even up to two hours, before it has to come up for air. Unlike humans, for whom each breath only replaces about fifteen percent of the oxygen we need to survive, a whale’s breath replaces ninety percent. It does so not only by filling the lungs; its muscles are rich in oxygen-storing proteins, and can store ten times more than humans’ can. A whale effectively has its own, personal, default-issue oxygen tank.

When the whale dives, its metabolism slows down to conserve oxygen. Its blood concentrates in vital organs including the heart and the brain; a net of blood vessels surrounds the brain and maintains oxygen levels and blood pressure to that organ, which is the largest of any living animal’s (even larger than that of the blue whale, which is the largest animal that has ever lived). The lungs collapse, and the ribs hinge shut around it. The trachea is fortified by extra rings of cartilage, which allow nitrogen to be stored there rather than dissolved into the tissues—a process that causes a potentially fatal condition called decompression sickness or the bends.

A whale can get the bends if it surfaces too fast; it’s not immune. But it’s extremely well protected by its physiology, and except under extraordinary circumstances—such as sonic shock from military sonar experiments—it can both dive and surface safely. Its whole body is designed for it. It’s meant for the abyss, and it thrives there, even though it’s an air-breathing mammal descended from one that, not so terribly long ago in evolutionary terms, walked on land.

icon-paragraph-end