There’s nothing new in the rationale behind the decision, but The Economist says it has not included Ireland in its ranking on the world’s richest countries, because our GDP calculations are “polluted” by the fact that global corporations declare profits here to take advantage of our lower corporation tax rates but then repatriate those profits.

We are not “truly rich”, they have decided. Ouch. One wonders if the snub caused any of the hapless crew managing the country at the moment to wince as they headed out to post social media snaps from their over-priced Oasis concert.

The annual ranking of the richest countries published by The Economist doesn’t just look at GDP per person, but also uses two additional measures: the impact of prices or cost of living, and what might be described as a holistic measure – how many hours people work to earn their wealth. Using all three measures, Forbes says, gives a more “realistic overall view of a country’s wealth relative to its inhabitants”.

It’s rather disconcerting if unsurprising, then, to see that The Economist decided to lump Ireland into a group of countries not included in the data because, as Forbes says, ” it’s almost impossible to get accurate data”.

The Economist says that Ireland GDP calculations “are polluted by tax arbitrage” and that this distortion means we are not a “truly rich” country. They are, of course, entirely correct, and as tariff wars deepen and we face the prospect of losing much of that corporation tax largesse that has been covering our massive public spending, it is long past time that we considered what that reality means and what it should prompt in terms of developing our own resources.

Our massively inflated GDP has long been the cause of international comment and criticism. The Economist has said our economy is “riding high in tech and pharma – for now” and that our good fortune is due to “global tax-shifting”. As they observed, our huge excess tax intake is unrelated to our workforce, a very worrying indicator whose significance has increased exponentially in recent months.

It’s almost 10 years since U.S. economist Paul Krugman described the ridiculous 26% rise in Ireland’s 2015 GDP as “leprechaun economics”, underlining how distorted our GDP and tax take is by what we now know to be just a handful of enormous corporations, including Apple and Microsoft declaring profits here.

As I pointed out last month, the Irish Fiscal Council have consistently warned against using GDP as a metric and advised the use of GNI (Gross National Income) instead, which is based on domestic activity.

Previously, my colleague Matt Treacy, in looking at figures for 2022, observed an enormous difference in GDP and GNI for that year: GDP for 2022 was €500 billion while GNI was €360 billion, he observed – a huge difference of €140 billion or 28%.

Similarly, while our GDP to debt ratio at that time looked healthy, in fact the ratio that actually mattered – the ratio of public debt to our GNI – was a different story entirely at 86%, equal to a per capita debt of €44,250 for each person living in the state.

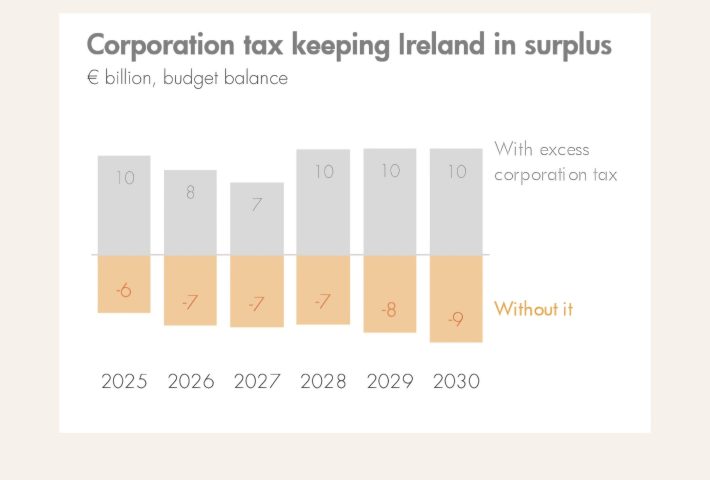

The Fiscal Council has repeatedly pointed out that “phenomenal levels of excess corporation tax receipts” are acting to “keep Ireland in surplus, but that the government is taking a significant risk in relying on these windfalls, adding that “rising ageing pressures would make this difficult to reverse”.

Their helpful chart showing Ireland’s situation without the excess corporation tax that we cannot rely on is essential reading.

Source: Irish Fiscal Advisory Council

This is what The Economist means when it says we are not truly wealthy: we are not producing enough actual income to put us in that category and are relying on taxes that could vanish quickly to maintain public spending. That spending also drives up inflation, of course, making cost of living harder for citizens, and allows the state to fund hugely damaging policies such as untrammeled immigration and a frankly insane asylum system.

Tax arbitrage, by the way, is the practice of declaring income and capital gains and transactions in the country that charges the lowest or most beneficial rate of tax. Is Ireland’s economic data “polluted” by that practise? Yes, of course it is. What have successive government done to offset the inevitable shock to the economy that a correction will bring? Almost nothing. And do we feel “truly rich” when our kids can’t afford to buy, or even rent, a home – and now can’t even afford college accommodation and are emigrating in droves? No, we don’t.

The Economist ranks Norway, Qatar and Denmark as the top three wealthiest countries when GDP is adjusted for local prices and hours worked. Belgium and Switzerland are 4th and 5th. The United States comes in 6th after adjustments although it is often described as the world’s biggest economy.

As the storm clouds gather, we might do well to scrutinise how successful countries use and develop their key resources, because we may very soon have the rug pulled out from under us and realise that the deficit between tax and spending can no longer be avoided.