China’s dominance over rare earths gives Beijing powerful leverage in trade, technology and strategic negotiations.

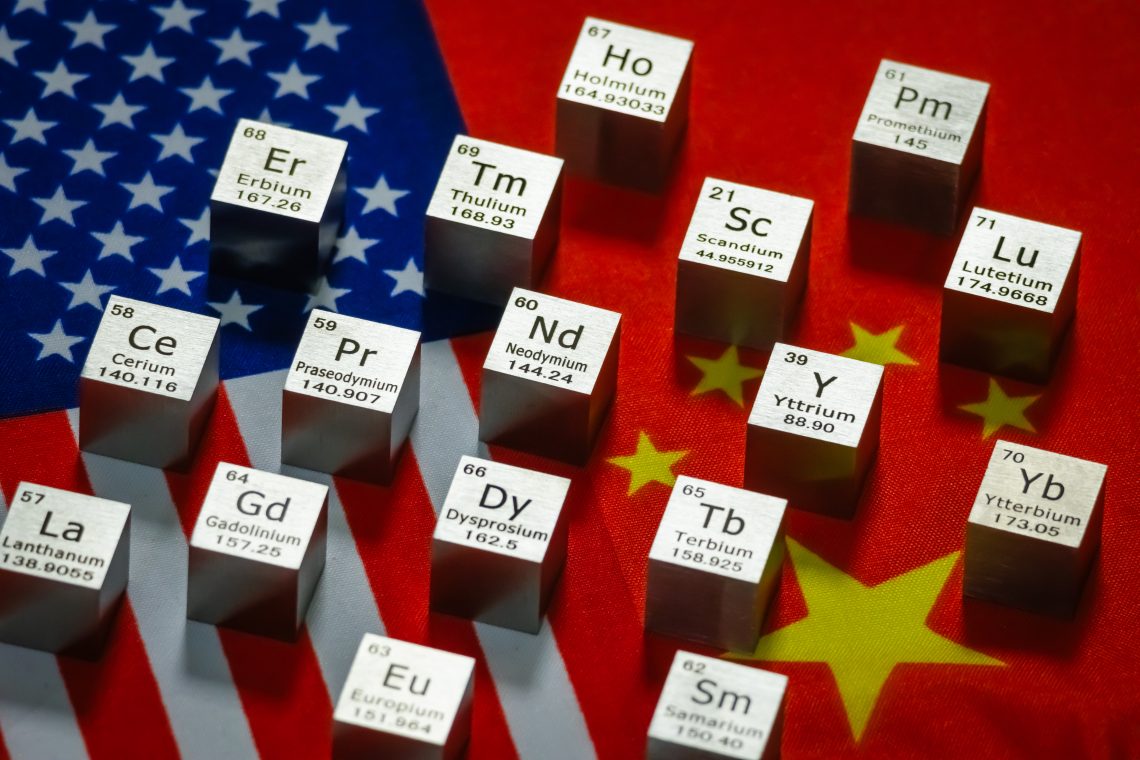

Metal cubes representing rare earth elements including neodymium (Nd), praseodymium (Pr), dysprosium (Dy), terbium (Tb) and others are displayed with their symbols and atomic numbers on overlapping flags of the United States and China. © Getty Images

Metal cubes representing rare earth elements including neodymium (Nd), praseodymium (Pr), dysprosium (Dy), terbium (Tb) and others are displayed with their symbols and atomic numbers on overlapping flags of the United States and China. © Getty Images

×In a nutshell

- Beijing uses rare earth export controls to pressure the U.S. in trade disputes

- U.S. alternatives remain slow, costly and technologically challenging

- China’s monopoly will likely persist, reshaping economic and political power

- For comprehensive insights, tune into our AI-powered podcast here

Back in 1992, Deng Xiaoping said: “The Middle East has oil, China has rare earths.” When he made this statement, he originally intended to show that while oil was scarce in China, rare earth deposits were plentiful. But he likely did not think that today’s Chinese leaders could use rare earths as a weapon of resistance and pressure against the United States and other Western nations.

As the administration of President Donald Trump engages in an economic standoff with China and threatens massive tariffs, Beijing weaponizes rare earths and magnets. In April, the Chinese government restricted shipments of seven rare earths to the U.S. and other countries. In response, Washington has somewhat softened its tone and extended trade negotiation deadlines with China to prevent a more dramatic halt of American access to crucial materials.

Dependence on China

China has invested billions of dollars in mines and processing facilities since 2000. Like in countless other strategic industries, China has utilized huge state subsidies, with little regard for environmental or safety standards, to produce rare earths at a lower cost than its Western competitors. This strategy has allowed China to acquire a monopoly on rare earths.

China’s dominance is reflected in its massive seizure of raw materials from both domestic and foreign sources (in 2024, China’s rare earth reserves were the largest in the world) and in the country’s rare earth production accounting for nearly 70 percent of global processing of the materials. The U.S., for example, currently gets about 96 percent of its rare earths from China.

To make its monopoly durable, Beijing has used every means at its disposal to extract as little of its rare earths as possible, while acquiring some from other countries as well. Currently, only one-third of the rare earths produced and processed in China come from domestic sources, while two-thirds come from foreign minerals. Of the foreign minerals, two-thirds are from Myanmar. These are cheaper than China’s because their deposits are on the surface rather than deep underground, while the country’s proximity results in lower transportation costs.

×Facts & figures

What are rare earths?

The so-called processed rare earths are actually a “basket” of 17 elements. They are not all derived from rare earths, which are divided into heavy and light rare earths. For example, China controls almost 100 percent of the world’s supply of dysprosium and terbium, which stem from heavy rare earths.

Australia, which cooperates with the U.S., has the potential to become the world’s second-largest source of light rare earths after China, supplying 15 to 20 percent of the world’s neodymium and praseodymium. However, Canberra acknowledges that the country is unlikely to be able to “fully replace” China’s supply capacity in all 17 rare earth elements.

Other aspects of China’s monopoly on rare earths include the country’s control of separation and refining equipment and technology, which has been largely forgotten or abandoned in the West. In recent years, despite its efforts to build its own rare earth mining and processing industry, American production of rare earths is far from meeting its demand.

Due to China’s control over rare earths, automakers in the U.S., Japan, South Korea, Germany and India have warned that rare earth shortages could force plant shutdowns. Now, because of China’s intensified weaponization of rare earths, this is becoming a reality.

Weaponization of rare earths

The weaponization of rare earths began back in 2010. At that time, China and Japan were engaged in a diplomatic dispute over the Diaoyu Islands, and in an effort to force Japan to submit to China’s will, Beijing restricted rare earth exports to Japan. This move threatened the Japanese automobile industry, and subsequently Japanese companies have been making efforts to manufacture products without relying on Chinese rare earths, which has not turned out to be very successful.

In 2018, during the first Trump administration, China began imposing controls on global rare earth exports, and it was the U.S. military industry that was primarily affected. Nevertheless, the U.S. showed little urgency in creating its own rare earth supply chain. At the time, it seemed there were enough informal channels to obtain the required rare earths, for example, through third countries such as Thailand or Mexico, who in turn sourced them directly from China.

In December 2023, when Joe Biden was the U.S. president, Chinese authorities imposed strict export controls on rare earth processing and refining technologies. This year, several additional regulations have been introduced to further restrict the export of rare earths, with the aim of using the materials as a bargaining chip with Western countries, especially the U.S., in exchange for things Beijing urgently needs, such as advanced microchips or markets for goods made in China.

Trump’s tariff war and Xi Jinping’s response

As the world’s largest manufacturing nation, China is a central focus of President Trump’s trade war, and the U.S. trade deficit with China is enormous. President Trump believes this imbalance has led to the disappearance of some U.S. industries. But he appears to have underestimated the strength of his trade war opponent. President Xi Jinping has experience from the trade war during Mr. Trump’s first term, and his stance is straightforward: He matches conciliation with conciliation, and escalation with even greater resolve.

So, when President Trump announced higher tariffs against China in April, China’s Ministry of Commerce decided to implement a variety of heavy-rare earth export controls as a countermeasure. The U.S. tariff threat on Chinese goods peaked this spring at 145 percent and Chinese levies on American imports reached 125 percent. Yet both sides pulled back from the brink. In early August, Washington’s tariffs on Chinese goods were 30 percent and Chinese levies on U.S. goods were 10 percent. Nevertheless, these developments have disrupted U.S.-China trade.

On the U.S. side, rare earths are essential to the automotive industry as well as defense and technology sectors. America’s “Big Three,” the traditional leaders in the country’s automotive segment (General Motors, Ford and Chrysler), were facing supply-chain and manufacturing disruptions when China’s rare earth restrictions reached their peak. The highly cumbersome control system designed by Beijing requires applications for exports several times annually. This not only lengthens companies’ shipment cycles, but also shakes international customers’ trust in Chinese supply.

For their part, Chinese officials ostensibly approve rare earth exports to the three major U.S. automakers, but only enough for a few months’ supply. China has also limited exports of certain magnets, complicating manufacturing for Western electric vehicle manufacturers. Beijing’s aim is clear: to limit or even stop offering the U.S. military industry access to rare earths. If the ban lasts a long time, the U.S. defense industry could face major disruptions in the production and supply of critical weapons systems. And it is partly happening already.

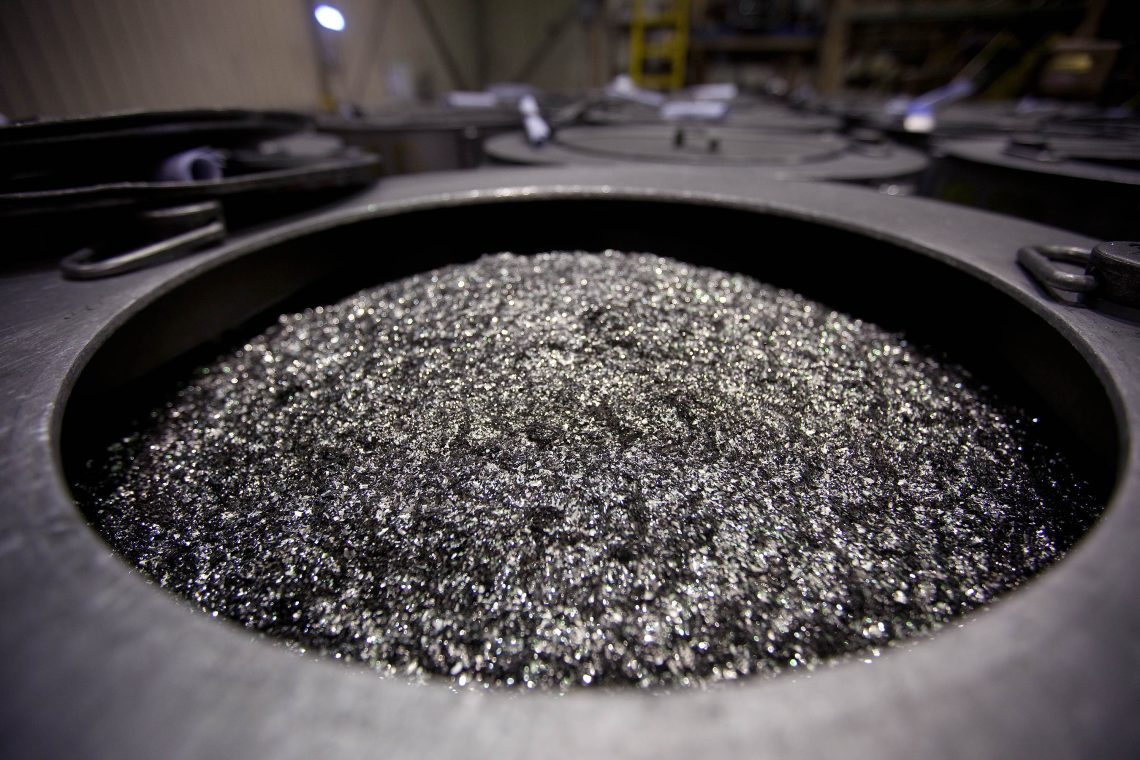

Annealed neodymium iron boron magnets in a vessel prior to being crushed into powder in Tianjin, China. © Getty Images

Annealed neodymium iron boron magnets in a vessel prior to being crushed into powder in Tianjin, China. © Getty Images

Since July, Chinese measures have made it nearly impossible for the U.S. military industry to bypass the Chinese market by buying from other countries. As a result, American military and automotive companies are facing a serious crisis due to the rare earth shortage, which forced the Trump administration to suddenly implement a new ban on the sale of “sensitive products” to China. The bans focused on three areas: ethane (a compound used to make plastics), Electronic Design Automation software (tools used by engineers to design electronic systems and circuits), and aerospace equipment and engines. But this has not made Beijing change course.

In this fight, President Trump appears to be blinking first. In early May in Geneva, the U.S. and China held talks in which they reached an agreement to give both sides 90 days to temporarily freeze most reciprocal tariffs, and in June, talks on tariffs were also held in London. The extensions were renewed again in August. In the talks, President Trump has asked China to resume rare earth exports and, as a gesture of goodwill, said the U.S. would ease restrictions on the export of certain products, for example, specific chips, engines for Chinese aircraft or easing restrictions on Chinese students’ access to U.S. universities.

But Beijing has not acted fully on President Trump’s announcement. China eased the export of rare earths to industries in civil fields but maintains complicated approval procedures. In contrast, there has been no substantial easing of restrictions on rare earth exports to the U.S. for the defense industry. Beijing has even adopted stricter controls on rare earth exports of certain heavy metals, to the point where exports to the U.S. of two heavy rare earths, terbium and dysprosium, fell to zero throughout the months of May and June.

The purpose of China’s weaponization of rare earths is clear: to force the White House not only to return tariffs to previous levels, but also to force the U.S. to end its control over the export of advanced chips and to demand that the U.S. relax its restrictions on Chinese students studying in America (especially in science and technology). The U.S. has somewhat cooperated on chip exports, agreeing in August that American semiconductor leaders Nvidia and AMD may export some advanced chips to China on the conditions the companies share 15 percent of revenues from the sales with the U.S. government.

U.S. response to Chinese export controls

Unlike the Biden administration, the Trump administration is not shy of using non-market methods to face the situation. The U.S. is trying to poach Chinese technicians to participate in local rare earth development. In response, Chinese officials have been strengthening control over rare earth professionals by withdrawing their passports and intentionally dividing the rare earth processing technology program, which was originally under the control of one person or one team, into several modules controlled by several people and teams, so that even if one or two of the module’s technicians go to the U.S., the competitors will still not be able to master the entire processing program.

Another method used by the Trump administration is to seize rare earth mineral resources from China by interacting with countries in Africa and Latin America. The administration even intended to cooperate with Myanmar to compete with China’s rare earth grabbing.

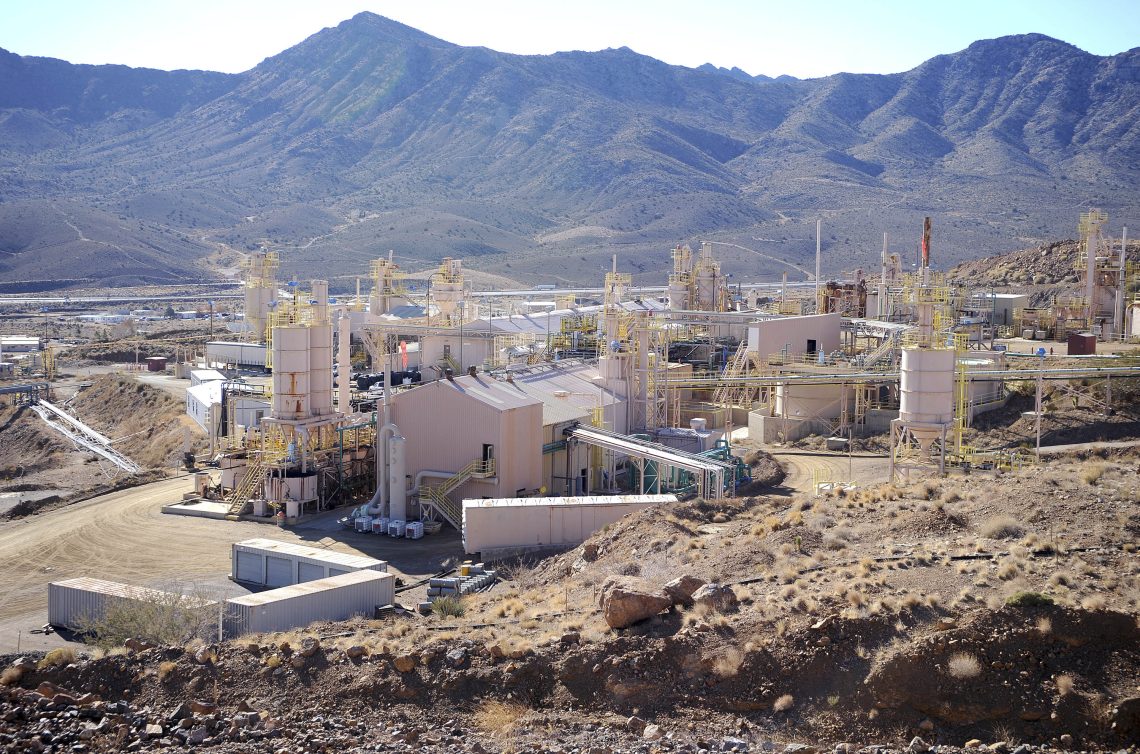

Mountain Pass, California, where the rare earth carbonate mineral called bastnaesite is mined. The location does some processing but much of the material is sent abroad for refining. © Getty Images

Mountain Pass, California, where the rare earth carbonate mineral called bastnaesite is mined. The location does some processing but much of the material is sent abroad for refining. © Getty Images

Lawmakers in the U.S. have produced several rare earth bills in the last decade and Americans have sought to create supply chains for rare earths outside of China, but to little avail. The U.S. Department of Defense allocated more than $100 million to Australia’s Linux earlier this year to build a rare earth separation facility in Texas. Yet Mountain Pass is still the only rare earth mining company in the U.S., with less than 5 percent of the world’s total production capacity.

The U.S. not only has to solve a mineral source problem, but also faces the problem of investment for processing and refining technology. And even if the production of rare earths is addressed, the price of this threshold is difficult to cross because international customers will be used to China’s pricing benchmark. Keep in mind that U.S. rare earth miner MP Materials in California suffered a net loss of $65.4 million last year as a result of China’s low-price strategy.

Read more on rare earths and critical minerals

There are signs that the U.S. is now learning from China’s policy of subsidization. The U.S. government is accelerating its push for an independent rare earth pricing mechanism that would provide price subsidies to support mining companies in an attempt to stimulate investment in the industry. The government will set a minimum purchase price for MP Materials at nearly double the current market price. But even so, it is hard to imagine the U.S. subsidizing the industry as heavily as China has. That is because such a pricing mechanism, while certainly favorable to rare earth producers, could push up costs for downstream consumers and customers, such as automakers. It therefore remains uncertain whether the industry can achieve scale without additional state intervention or other non-market measures.

×

Scenarios

Unlikely: The U.S. develops rare earth processing swiftly

Even if all goes very smoothly, it will take about four to five years before the U.S. can develop some rare earth processing capacity. In short, the Trump administration has to recognize that decoupling from China’s rare earth supply chain will be very difficult to achieve within his term in office. This is also reflected in recent policies: Although it has not ended regulations on China’s advanced chip restrictions, the U.S. government has notified major companies to relax restrictions on delivery of chips to China, hoping to gain “tolerance” from China’s rare earth exporters in exchange.

Likely: China to remain in the rare earths’ driver’s seat

China effectively maintains its monopoly for a decade. As Beijing is weaponizing rare earths, Washington is forced to perpetuate a softening of its own policy toward China. As a result, the U.S. will not be able to decouple from China as fully as it desires. The U.S. might be able to maintain its superiority in some individual technological areas, but American dominance of the global economic order and its geopolitical primacy will be diminished. Rare earths will become the real ace up China’s sleeve, which it can use for decades. Nevertheless, Beijing’s policy could backfire, as it is already creating immense dissatisfaction among Western non-military industries and even contempt among those in the U.S. defense industry.

Contact us today for tailored geopolitical insights and industry-specific advisory services.

Sign up for our newsletter

Receive insights from our experts every week in your inbox.