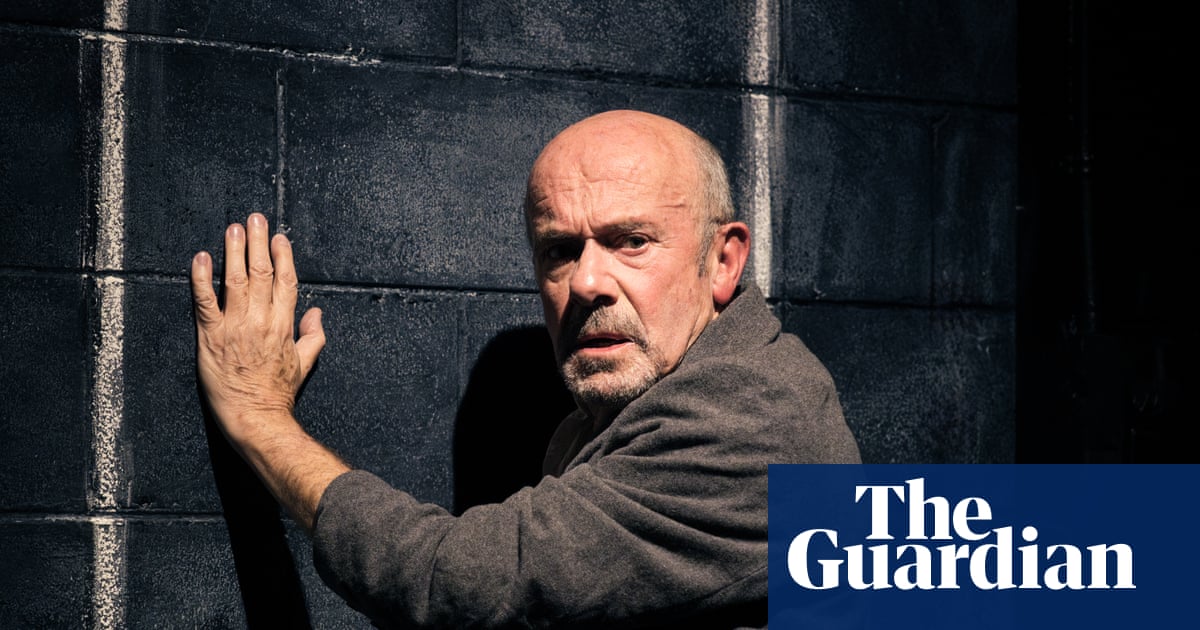

Robert Meldrum stalks the stage of the Explosives Factory in St Kilda in a long coat and hat, bewildered and buffeted by a lifetime of memories, grappling with grief and attrition in a dimming and desolate landscape. He’s not suffering from any loss of faculties; he’s simply an actor inhabiting the world of Samuel Beckett.

Meldrum and his director and longtime collaborator, Richard Murphet (both in their mid-70s), are preparing to open Still, a compendium of six monologues cobbled from the Irish writer’s later works. While it speaks to universal themes of resilience and despair, it also captures the experience of any ageing actor who puts their body through the nightly rigours of stage work. As Beckett says in his 1953 novel The Unnamable, “ … you must go on. I can’t go on. I’ll go on.”

“I don’t think I could in any way have done this in my 20s,” says Meldrum. “My ability to be completely still and present enables me to go into this work in a way I couldn’t before.” Murphet agrees, adding that Beckett’s “understanding of age and of maturity, the wealth of experience laid on top of you, is really deep. I sense it would be very difficult for a young person to do this.”

As a culture we tend to talk about ageing as a series of losses, a whittling away of vigour and ability, but talking to actors in the latter part of their career reveals something more complex and moving. Apart from obvious issues with mobility and strength (Meldrum jokingly mentions “walking around and going up and down stairs” as areas of difficulty), these performers feel freer and more focused than ever.

“I feel I’m performing the best I’ve ever performed,” Meldrum says. “As far as the idea of age slowing you down, it’s been a positive for me because I’ve always been a bit speedy.” Working with young actors as a lecturer at Victorian College of the Arts and now at the National Theatre, he notes the biggest challenge “is getting them to be still, not to constantly think ahead. It’s huge. Maybe it takes a lifetime?”

Evelyn Krape in Yentl, the 2024 production at Malthouse, Melbourne. Photograph: Jeff Busby

Evelyn Krape has experienced something of a career renaissance lately, wowing audiences in Kadimah Yiddish Theatre’s production of Yentl, playing an ancient mischievous spirit – an irrepressible agent of chaos scampering up ladders and jumping on beds. She also recently finished a run in Tom Gleisner and Katie Weston’s musical Bloom, carrying the emotional stakes of the show as a vibrant, colourful woman coming to the end of her life in a soulless nursing home.

The latter is a rare naturalistic, age-appropriate role for 76-year-old Krape, who has specialised in a more freewheeling and vaudevillian performance style, notably in the plays of her late husband Jack Hibberd.

“I’ve never really played my age. In Dimboola I played a nine-year-old girl. At 21, I played Granny Hills in the Hills Family Show, where I had thick knitting yarn sewn in between two stockings to give me varicose veins.”

Le Gateau Chocolat and Paul Capsis in Black Rider at the Malthouse in 2017. Photograph: Pia Johnson

At 61, actor and cabaret legend Paul Capsis is younger than Krape and Meldrum, but after the recent death of his mother he’s found himself thinking about second acts and what his might look like.

“If anything, I’m planning on being crazier and more debauched,” he jokes over the phone from Lisbon, where he’s having a break before starting rehearsals for Sydney Theatre Company’s upcoming production of The Shiralee. “Because I don’t feel any different, you know? I still think I’m 35 – and then my body goes ‘Oh hell no, bitch!’”

Capsis doesn’t necessarily place restrictions on himself as a performer these days, but he does want more agency over certain conditions. “I’ve turned down gigs because they were asking me to sing in that countertenor range, and I just don’t want to do that to my voice any more. I’m also much more interested in a director’s process. I want to know as much as I can before going in.”

skip past newsletter promotion

Sign up to Saved for Later

Catch up on the fun stuff with Guardian Australia’s culture and lifestyle rundown of pop culture, trends and tips

Privacy Notice: Newsletters may contain info about charities, online ads, and content funded by outside parties. For more information see our Privacy Policy. We use Google reCaptcha to protect our website and the Google Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.

after newsletter promotion

While fear – of forgetting lines or blocking, or folding under the pressures of a long run – can increase with age, so too does confidence in one’s skills. “I feel more certain about myself as a performer,” Krape says. “I’m not afraid to really go for things and if they work, they work. If they don’t, you try something else.”

All the actors Guardian spoke with mentioned wanting more time in the rehearsal room. Most commercial theatre productions have a three-week rehearsal period, “which is not enough”, says Capsis. “Not nearly enough.”

“A gift for an actor is a second or third season,” says Krape. “Because you can’t help but scratch the surface the first time. If you don’t get that time to really play, things are more token and superficial.”

Meldrum and Murphet extended their rehearsal process over an entire year. It’s a method drawn from famed European theatre companies such as Berlin’s Schaubühne or Peter Brook’s Bouffes du Nord, where rehearsal periods are ongoing and open-ended. “There was no time frame [for Still],” says Meldrum. “We just worked until it was ready.”

Of course, financial constraints mean this type of deep exploration is rare. Most actors in Australia, even at the pointy ends of their careers, work hand to mouth and can’t afford to luxuriate over roles. Retirement seems almost unthinkable. “There’s still so much I want to do. I hope not to have to retire,” says Krape. Meldrum is blunter: “I can’t afford to retire.”

Why even countenance the idea when the work is so rewarding and the contributions these actors make are so vitalising for an industry often transfixed by youth? Murphet says the work “keeps me alive, it keeps me energised. And if I wasn’t doing it, then I would slip into senility. So I can’t say that there’s anything about it that makes me feel old, because there isn’t.”