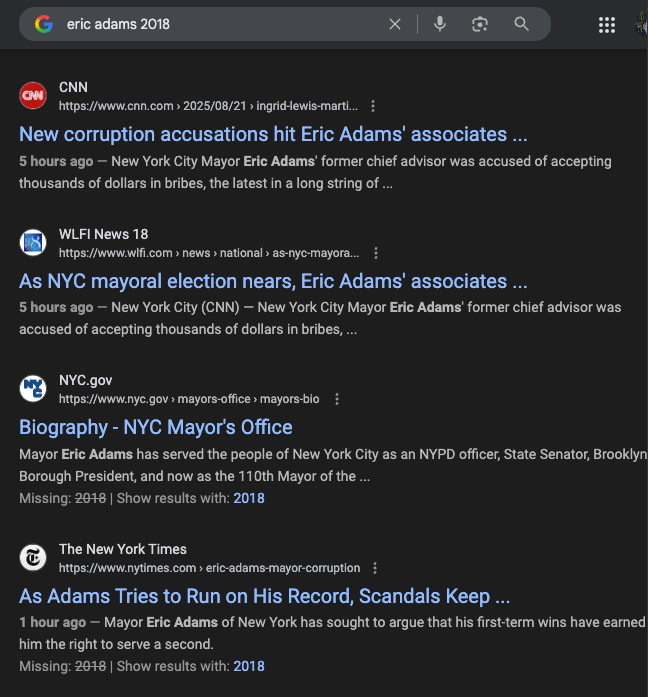

About a year ago, I bought a hardcover thesaurus—Roget’s in dictionary form, the Delacorte edition, printed in 1992. It’s huge, it’s heavy, and it smells faintly of mildew, probably because it was sitting on a shelf in a New Orleans used bookshop for years. But it was a necessary investment, because when I Google synonyms for a word, I can no longer trust that the results I get will be accurate or useful. Or, for that matter, when I Google anything. Instead, some weird AI-generated gunk is likely to come up, or a “sponsored” ad, or both. Plenty of people online have noticed this phenomenon. Around the time I hoisted the jolly Roget, a series of viral screenshots showed that when people Googled the question “how many rocks should I eat each day?,” the search engine told them to consume “at least one small rock.” Its AI had apparently scanned a parody article from the Onion and treated it as a real information source. More recently, I’ve noticed that whenever I Google a politician’s name, even if I put a year like “2018” in the search field, I mostly get very recent news stories, and have to dig for the information I actually want. (Try it yourself, folks.) Google is shit now, compared to its former self. But why?

just look at this mess. embarrassing.

In his forthcoming book Enshittification: Why Everything Suddenly Got Worse and What to Do About It, tech writer and novelist Cory Doctorow offers some answers. It would be an exaggeration to say Doctorow created the concept of “enshittification”; back in 2018, Esquire’s Dan Sinker was writing about Facebook’s “enshittening,” and that same year Naked Capitalism blogger Yves Smith described the “crapification” of modern Boeing planes. But it’s certainly Doctorow who’s done the most to popularize the idea, to the extent that the venerable Merriam-Webster dictionary added “enshittification” to its roster of words this January. As they define it, the term means “the degradation in the quality and experience of online platforms over time,” whether it’s Google, Facebook, Twitter, or any other section of the internet. And as the book’s subtitle suggests, Doctorow believes he’s worked out both why it happens, and how to stop the shit from flowing.

On the first point, he has a strong argument. Doctorow’s main thesis is that Big Tech companies “enshittify” their products and platforms because they can. As profit-seeking enterprises, it’s their natural tendency: “companies would like to charge as much as possible for goods and services while spending as little as possible on… anything” that makes the consumer’s experience better. In the past, he writes, there have been countervailing forces that prevented tech companies from making their products as shitty as they’d like. The four most important are competition from other companies, regulation from the government, resistance from a skilled workforce that doesn’t want to make junk, and savvy consumers who will hack and modify their tech. But as the companies in question become larger and more powerful, often becoming monopolies, each of these obstacles to enshittification has become less and less effective, and company executives have pushed the envelope more and more.

Doctorow breaks down the shit-making process into four steps. First, there’s an initial period where a company launches a website or a piece of software, and it’s great for users. Think Facebook or Google, circa 2010. Douglas Adams once quipped that “we are stuck with technology when what we really want is just stuff that works,” and these early-stage platforms just worked. They did the things you’d expect them to do, simply and effectively. Everyone liked using them. And because they did, they got “locked in.” All their friends and photos were on Facebook, or all their carefully-curated music playlists were on Spotify, so it would be a major pain to switch to a different platform. Once enough people are locked in, the company moves to Stage Two: abusing their users on behalf of business clients. They put more and more ads into your feed, or they collect more and more data about your online habits and sell it off to the highest bidder. That way, the business clients become “locked in” too, because they need access to all those users to sell their products and services. So the Big Tech companies move to Stage Three, and they abuse the business clients too, charging more and more money to place ads, manipulating algorithms to boost some clients and bury others, and all kinds of other chicanery. Finally, Stage Four arrives: the once-great platform is now awful for both the average users and the business clients, but everyone’s trapped there, while the tech CEOs vacuum up billions of dollars. Enshittification is complete.

Take Amazon, one of Doctorow’s most compelling case studies. Initially, it was great for customers: “The company raised a fortune from early investors, and then a larger fortune by listing on the stock market. Then it used that fortune to subsidize many goods, selling them below-cost. It also subsidized shipping and offered a generous, no-questions-asked, postage-paid returns policy.” This attracted a massive consumer base and allowed Amazon to kill off many of its competitors (RIP, Sears catalog and Diapers.com). The Prime subscription program, introduced in 2005, got people “locked in” for long periods of time. Then the search engine changed. instead of showing you the best match for the product you’re looking for, it now shows you whichever sellers paid a premium to have a “sponsored” result, and the item you actually want is on Page 2 or deeper. That locked in the sellers, and now Amazon exploits them too, becoming more and more extortionate: “Add all the junk fees together, and an Amazon seller is being screwed out of 45 to 51 cents on every dollar.” The company even copies popular products to make “Amazon Basics” or “Essentials” versions and buries the original sellers in the algorithm, sometimes driving them out of business.

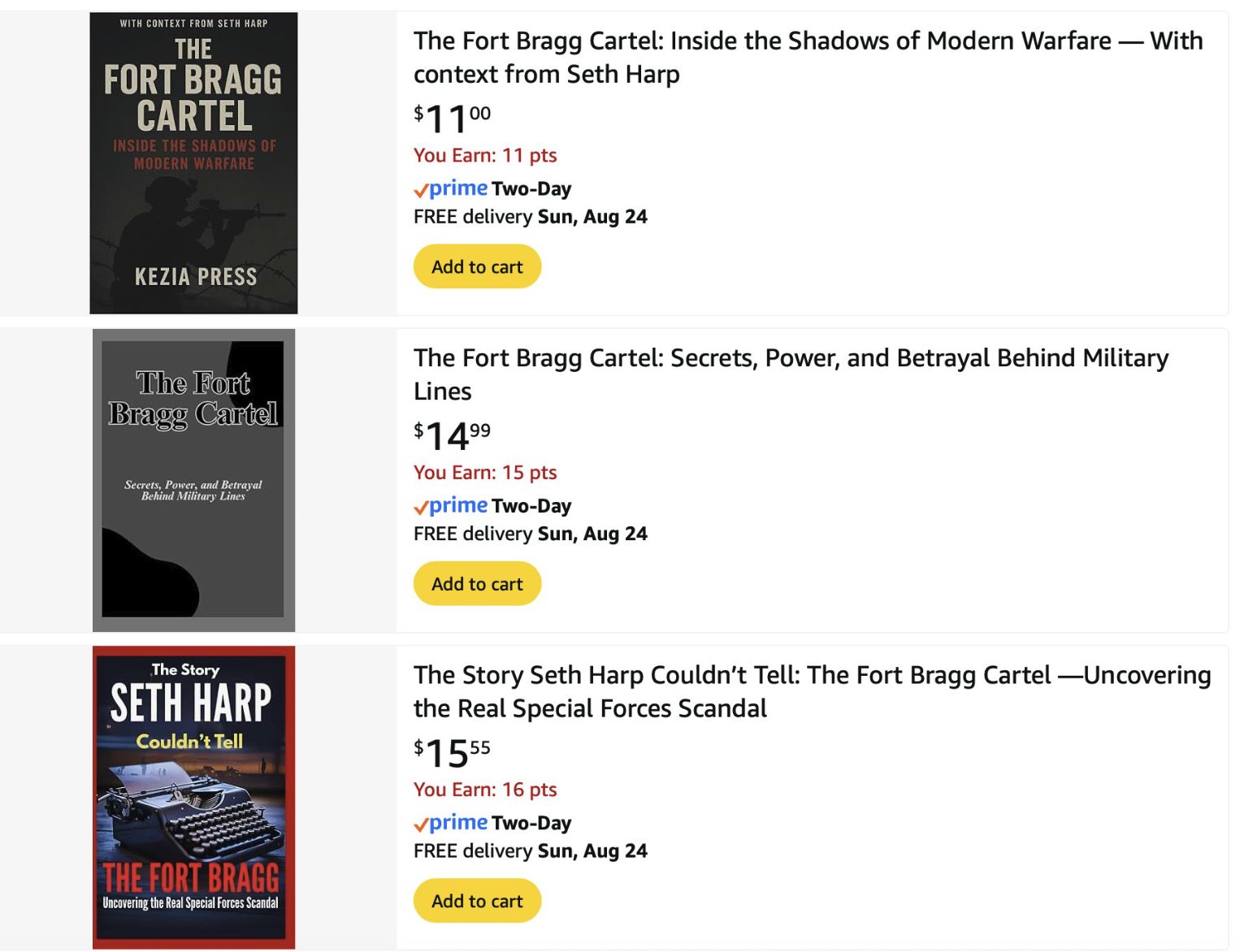

In 2025, Amazon is thoroughly enshittified. The site started as a bookseller, but nowadays when you search for a book, you’ll find umpteen AI-generated knockoffs or “summaries” of that book cluttering up the page, which Amazon seems to be in no hurry to remove. Investigative journalist Seth Harp, who recently released a bestselling book called The Fort Bragg Cartel about drug trafficking on U.S. military bases, has been the latest victim of this phenomenon:

Image: Seth Harp via Twitter

But aside from knockoffs, the platform is also full of low-effort pseudo-books. Take the biography series “Titans of Power: The Lives That Shaped Politics,” which contains 19 short books (and counting!) about different politicians, all summarizing information you could find on their Wikipedia pages with a plain blue cover. (My favorite: The Relentless Will of Tim Burchett.) Amazon is absolutely clogged with stuff like that.

It’s the same when you search for a clothing item—look up “men’s Oxford shirts,” for example, and a lot of the top results are either Amazon Essentials or weird all-caps brands like “COOFANDY,” “CIGENU,” or “J. VER,” which list their origin simply as “imported” and use only the finest polyester. You have to scroll for a while to find anything halfway decent, and because roughly 43 percent of Amazon product reviews are fake now, you can’t trust any of the information you find there, either. Meanwhile, Jeff Bezos has never been richer.

Or, for another example, consider Facebook. It’s hard to remember now, but Facebook was fun to use at one point. There’s a reason it overtook Myspace to become the dominant social media site. But here again, the same pattern Doctorow identified has played out. The site got so many users they were all mutually “locked in”; it started shoving ads down their e-throats and tracking their every click; then it started ripping off the companies that buy the ads, to the extent that “In 2018, Proctor & Gamble zeroed out its $200 million annual ‘programmatic advertising’ budget” and saw no reduction in sales. More recently, Facebook has also gotten rid of its fact-checking staff, and the site has been flooded with all kinds of bizarre nonsense. According to one estimate, as much as 40 percent of new Facebook posts may be AI-generated. If you want to see an oddly shiny image of Jesus made out of shrimp, that’s your place.

Zoom out a little, and we can see that broader political and economic forces have been at work to make all this possible. One, Doctorow writes, is the gradual abandonment of antitrust law by American politicians since the 1980s. In the past, the U.S. government would break up companies that became too big or powerful; this is what famously happened to Standard Oil in 1911, creating several smaller companies like Chevron and ExxonMobil that are still around today. But even more recently, the Nixon, Ford, and Carter administrations made a serious attempt to break up IBM.

This is a fascinating chapter of U.S. corporate history, and Enshittification brings it to life. IBM, Doctorow says, was “tech’s first great monopolist,” and it pressed its advantage the same way Amazon and Google do today: it “gouged its customers on some of its products, and used predatory pricing, long-term exclusivity contracts, and engineering tricks to prevent competitors from entering the market.” The federal government, which had IBM hardware in practically every office, was the biggest client to get ripped off, and they got sick of it. So Republican and Democratic administrations alike waged a twelve-year legal battle that was later dubbed “antitrust’s Vietnam.” It ended when Reagan got into office, and IBM ultimately stayed intact, but it made a difference. After being under government scrutiny for so long, IBM halted some of its worst anti-competitive practices, and smaller, newer companies like Microsoft and Apple were able to get a foot in the door, creating the computing landscape we have today. But ever since Reagan, both Republicans and Democrats have gradually abandoned antitrust enforcement, and that dereliction of duty has allowed new monopolists and shit-merchants to flourish.

Another critical factor is the steps companies have taken, both on the legal and the engineering front, to restrict the ways in which consumers can use their technology. In the past, Doctorow says, tech users would resort to “self-help” to fix or get rid of any tech product they didn’t like, and this put a limit on how much enshittification companies could get away with. For example, if Microsoft Office added too many bloated, useless features—or tried to paywall existing features—people can just switch to a different word processor that can also read .DOCX files. Or if ink cartridges get too expensive, people could stop buying them and use off-brand equivalents for half the price. But over time, companies have made technical changes to make “self-help” harder or impossible, and they’ve lobbied governments to punish the people who engage in it.

As Andrew Ancheta wrote for Current Affairs this May, Apple is one of the worst offenders here. It pioneered something called “parts pairing,” which means that many iPhones won’t accept any part that’s not “recognized,” including parts from an old scrap iPhone or ones made by a third-party company. Unless you’re particularly tech-savvy, this means you’re forced to either rely on Apple itself to fix your phone if it breaks—for a heavy price—or just buy a new one. Many printers use pairing now too, so only official (and expensive) HP ink will work in an HP printer without tinkering. Or with software, there’s the infamous Digital Rights Management (DRM), which makes it impossible to, say, take your Kindle books and put them on anything but the authorized Kindle platform, the way you could put a .DOCX document into any word processor. It’s not just engineering: thanks to the Digital Millennium Copyright Act, it’s also illegal to remove DRM from media files in many cases. So even though you theoretically bought your ebooks, Amazon controls how and where you can use them, and it reserves the right to modify or even erase them any time it likes. If it adds some awful feature to Kindle, you’re stuck with it.

Finally, there’s the labor side of things. An underrated brake on companies’ drive to enshittify, Doctorow says, is tech workers themselves. For a long time skilled software engineers and other technicians had leverage over the companies that employed them: they were “very hard to replace, and in enormous demand, so they had to be kept happy or they might defect to a rival.” That’s why companies like Google created their infamous playground-like “campuses” in the 2010s, full of free snacks and games. But another way they kept their workforce in line was by inculcating a sense of “mission,” bandying around high-minded slogans like Google’s now-defunct “don’t be evil” or Facebook’s “bring the world closer together.” This use of “mission” to keep workers in line isn’t unique to tech; it’s also used to manipulate and exploit doctors, teachers, nonprofit workers, and others who think of themselves as making the world better. But it also has a side effect. Having bought into the “mission” framing and made personal sacrifices to devote themselves to a company, many tech workers “experienc[e] a sense of betrayal and profound moral injury” when they’re told to enshittify their products, and refuse to do it. They have an inconvenient thing called principles.

Unfortunately, “tech has resolved its labor scarcity problem,” and is now firing and laying off workers at a record pace. It got help from the U.S. government, which ramped up the production of skilled tech workers through the STEM and “learn to code” education push of the 2010s—thanks, Obama. And increasingly, the industry is replacing tech workers with AI. Worse still, “tech union density is so low it can barely be charted,” so when workers are no longer scarce, they don’t have much power. So the situation is degrading by the day, tech workers are more and more likely to be forced into abusive “crunch” situations where they work 60-80 hour work weeks, and enshittification is accelerating.

Doctorow does a fine job diagnosing the problem. After more than 20 years writing about technology and the companies that make it, he knows the subject better than most people alive, and it shows in the book. But after a long examination of the rot spreading through today’s Silicon Valley techno-capitalism, we’re left with the perennial question: what is to be done? And that’s where I found Enshittification a little frustrating.

It’s not that the solutions Doctorow proposes are wrong, in and of themselves. In the back half of the book, he lays out a multi-part approach that mirrors his diagnosis. To solve the lack of competition that allows companies like Google and Amazon to operate as monopolies, he wants a return to the muscular antitrust enforcement of the early 20th century, and praises Biden-era Federal Trade Commission chair Lina Khan for her efforts to break up Big Tech. Fair enough. Khan was a superstar, which you could tell because the tech billionaires funding Kamala Harris’s campaign were emphatic that she should be fired. Anything that makes Reid Hoffman nervous is typically good, and things probably would get better if you, say, broke Amazon into five smaller companies. Doctorow also wants to see a large-scale unionization of the tech industry: again, a good and necessary idea. There have been some impressive victories here, like when more than 600 video-game workers at Activision unionized last year, and Doctorow is at his most compelling when writing about the crucial role organized labor plays in society:

Unions don’t just represent the workers who pay their dues; they represent labor, in solidarity, against the forces of capital. To effectively support their members, unions can’t confine themselves to fighting the employer—they have to fight corporate power itself.

Lastly, he urges new “right to repair” laws removing restrictions on how people can hack, fix, alter, and otherwise tinker with their tech, arguing that things like HP’s restrictions on ink cartridges violate the most basic concepts of personal property:

If your printer is yours[…] then it is certainly none of HP’s goddamned business whose ink you use. Hell, fill your printer with ditchwater if you want! Or with vintage Veuve Clicquot (which costs a fraction of what HP charges for ink).

Doctorow also points out that any government action will not originate from the government, but will come as a response to political pressure from below, noting that Lina Khan’s appointment was a concession to the Bernie Sanders wing of the Democratic Party. He urges more grassroots organization to create more of that pressure, in hopes it can generate even bigger results.

This is all well and good, as far as it goes. The problem is that it doesn’t go far enough. Throughout the book, Doctorow uses an extended medical metaphor, naming his sections things like “The Pathology,” “The Epidemiology,” and finally “The Cure.” But remember, he identified the root cause of enshittification as the profit-seeking nature of corporations themselves, as corporations. By nature, they “would like to charge as much as possible for goods and services while spending as little as possible on… anything.” And as good as they are in a vacuum, none of the proposals in Enshittification would remove that root problem. Instead of a cure, what we get is a series of palliatives.

In the book’s conclusion, Doctorow writes that he’s “no true believer in markets as the best arbiter of how our society should work,” and that “like other leftists, I am deeply suspicious of capitalism.” Elsewhere, he’s written favorably about China Miéville’s commentary on the Communist Manifesto. But with that in mind, it’s strange that the solution he arrives at isn’t particularly anti-capitalist or anti-market. In a memorable metaphor, he describes tech CEOs as showing up to work every morning, “going directly to the giant ENSHITTIFICATION lever installed in the C-suite and yanking on it as hard as they can.” But, he says, “the difference is that the lever used to be stuck. It was gummed up by competition, by regulation, by interoperability [users’ ability to easily switch software], and by tech workers’ power and conscience.” By restoring all of those things, he hopes to re-gum the lever.

But this is a limited horizon to aim for. It promises restrained and regulated tech companies, perhaps chastened and better-behaved, but it does not challenge the idea that for-profit companies should be the ones making and maintaining the technology we all rely on. The question remains: why should we accept the existence of a malevolent CEO with an enshittification lever at all? Instead of better-regulated companies, why shouldn’t the solution be no more companies?

It’s not like for-profit corporations are the only possible model. You can nationalize things. In Britain, Jeremy Corbyn’s incarnation of the Labour Party had a detailed proposal for a publicly-owned internet provider, which drove his critics berserk (the BBC called it “broadband communism.”) That would undoubtedly be better than for-profit monopolies like Comcast, which are common across the United States and often charge people absurd prices for sub-par service. Or, right here in the U.S., the IRS had a very promising pilot program to release its own “Direct File” tax-preparation website and provide a free alternative to the increasingly enshittified TurboTax. Right-wing critics of the program hated how it “competes with software from tax-preparation companies,” and they’ve successfully lobbied Donald Trump to kill it off. But having a public competitor was exactly the point, and if TurboTax can’t keep up with one, it deserves to die.

The same logic can be applied to a lot more areas. There’s no technical reason we couldn’t have a nationalized search engine to compete with Google, completely devoid of advertising or surveillance. That’s what the public library card catalog used to be. In an initial concept paper about Google, even Larry Page and Sergey Brin warned that “the issue of advertising causes enough mixed incentives” that it would be “crucial to have a competitive search engine that is transparent and in the academic realm,” suggesting it could be run by a public university or a consortium of them. You could even have public alternatives to social media networks like Facebook and Twitter, serving as the PBS to their Fox News. Plenty of people smarter than me have made the case that all major web platforms should be publicly owned, since they serve—or claim to serve—the purpose the “public square” did in previous eras. But a serious discussion of nationalization and public ownership is strangely absent from Enshittification. What we get in its pages is social democracy at best, not socialism. Reform, not revolution.

I’m really not sure why that is. In the past, Doctorow has never had an issue with seemingly radical political content—I still remember fondly his young-adult novels about people who illegally pirate and remix Hollywood films, or teenage hackers fighting the Department of Homeland Security. Maybe he’s made a calculation that in the current Trump administration, the best we can hope for is regulation and new trade unions, and that the Big Tech companies’ position is so dominant there’s no practical possibility of overthrowing them any time soon. Maybe he’s got some kind of libertarian concern about “big government.” In any case, I still think Enshittification is worth reading for its insight into how we got here. But considering the size of the shit-heap we’re facing, I can’t help but wish it provided a bigger shovel.