Facebook

Twitter

Reddit

WhatsApp

Messenger

Email

Print

In August 1939, the Soviet Union (despite its degeneration) remained a symbol of revolution and socialism for millions of workers around the world. In Britain, the Communist Party (CPGB) had around 17,500 members and was a significant force in the workers’ movement in Britain.

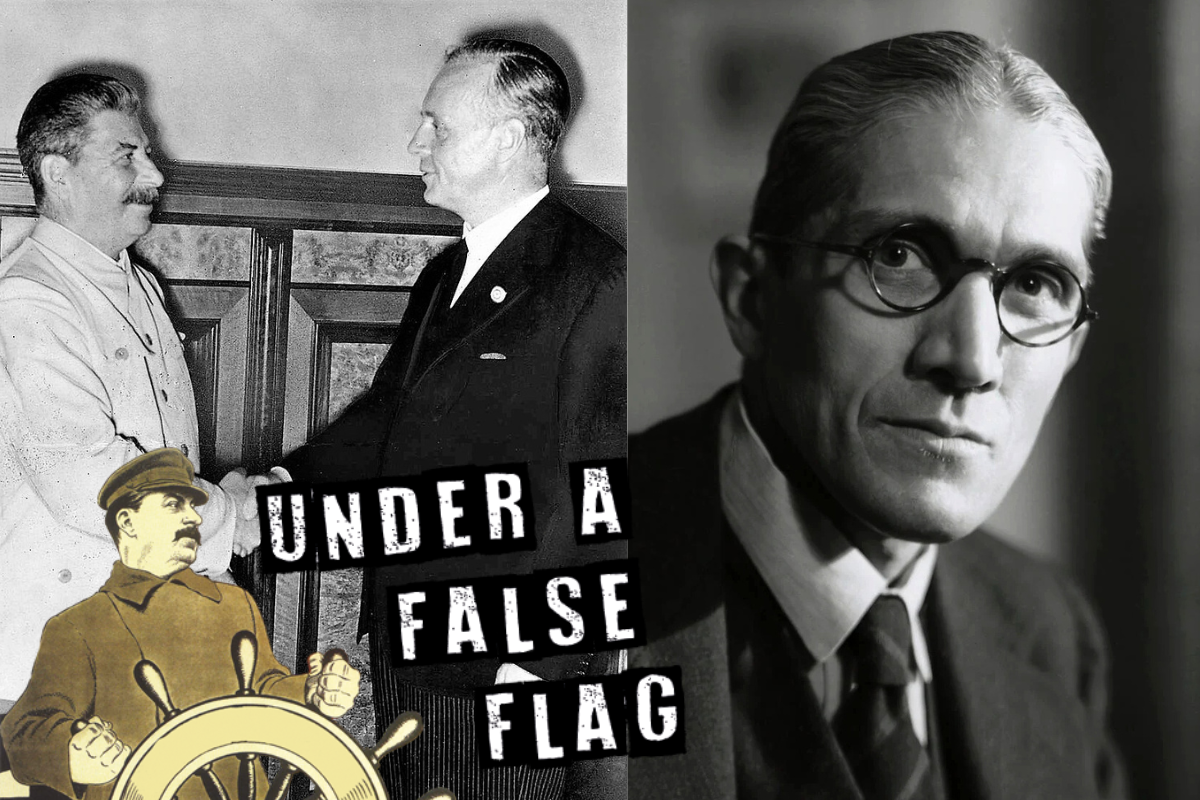

Both the CPGB and the international workers’ movement were thrown into chaos, however, with the signing of the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact. Named after the respective foreign ministers, this was a non-aggression pact between Nazi Germany and the Stalinist Soviet Union.

As a part of the pact, the Soviets sent immense amounts of raw materials to Germany, allowing Hitler to greatly expand his war machine. Tragically, this was turned against the Soviet people just two years later.

Secretly, the two powers carved up Eastern Europe into spheres of influence, including Poland, which was split into two.

Even the pliable leaderships of the Communist International (Comintern) were taken by surprise. In Britain, the general secretary of the Communist Party, Harry Pollitt, didn’t agree with the pact and was removed on Moscow’s orders. He made a return two years later when Hitler invaded Russia, and the Comintern reversed its policy.

And so the task of defending this latest manoeuvre fell to Rajani Palme Dutt, who became the general secretary of CPGB. Fully in agreement with Stalin’s actions, and looking to stay in his good books, he penned the pamphlet Why This War?

Peace front

The task of defending this pact fell to CPGB leader Rajani Palme Dutt.

The task of defending this pact fell to CPGB leader Rajani Palme Dutt.

Why This War? fails to acknowledge key factors, including the disastrous role of the Stalinist communist parties, whose actions enabled fascism to triumph in Germany.

Dutt does point out that Anglo-French imperialism financed and rearmed Nazi Germany in order to set it on the Soviet Union. But he completely overlooks the mistakes and betrayals carried by the Comintern leaders which allowed Hitler to come to power.

He then sows illusions in the possibility of peace between the imperialist powers on the basis of bourgeois diplomacy. But this flies in the face of what Lenin repeatedly pointed out:

“Under capitalism, peace is nothing but a truce between wars.” (Report on the International Situation and the Fundamental Tasks of the Communist International, 1920)

Imperialist peace, as Lenin often repeated, prepares the way for imperialist war. All the treaties and peace agreements in the world aren’t worth the paper they are written on once the tensions between the imperialist powers become untenable.

Ending the war therefore wasn’t a question of fighting for abstract ‘peace’ versus ‘aggression’, but a question of overthrowing capitalism, which necessitates inter-imperialist war.

The Second World War was not a result of the ‘peace front’ being rejected, nor was it a struggle for democracy against fascism on part of the ruling classes. The war was an inevitable result of the rotten Versailles ‘peace’, the deep world crisis of capitalism, and the failure of the Communist leaders to overthrow capitalism in the past period.

Only a revolution against the capitalist system itself could have prevented this war – not diplomatic manoeuvres with this or that capitalist state.

But Dutt, like Stalin, placed all his emphasis on bourgeois diplomacy as means to achieving peace.

“By their deeds the British and French ruling class have shown that they do not stand for the defence of peace against aggression. If they did, they would have agreed to the peace front, which would have prevented this war.” (Dutt, Why this war? 1939)

Accordingly, Dutt argues that Stalin’s hand was forced by Britain and France’s refusal to sign a formal alliance against Hitler.

Did this pact help fight fascism?

Stalin’s ‘defensive’ action threw the international workers’ movement into chaos, but it didn’t come out of nowhere. It was the direct result of the policy of the whole previous period: the zig-zags from the supposed ‘third period’ to ‘popular frontism’ had beheaded the workers’ movement and paved the way for fascist counterrevolution.

The pact was not inevitable but the culmination of Stalin’s policies of the whole previous period.

The pact was not inevitable but the culmination of Stalin’s policies of the whole previous period.

Through it all, the British Communist Party slavishly supported every twist and turn by Stalin and the bureaucracy. Its main role became to keep the workers’ movement in check, so the Soviet leaders could make agreements with the British ruling class.

In Britain, the Communist Party was pushed to tail-end the decisions of the TUC leaders, which contributed to the failure of the 1926 General strike.

In 1929, the Comintern adopted the ultra-left sectarian theory of ‘social fascism’, which argued that the Social Democrats and reformists were the ‘twin’ of the fascists, and therefore it was impermissible to form a tactical alliance with them. This divided and incapacitated the working-class movement, and allowed the fascists to sweep into power in Germany.

By 1933, when the disastrous result of this policy came to bear, instead of drawing a balance sheet, the Stalinists carried out an about-face. Now, they called for popular fronts with the same (supposedly ‘progressive’) capitalists who were responsible for the rise of fascism in the first place.

It was Stalin and his followers in the CPGB that disrupted the working-class movement and helped Hitler to come to power through their failures in the preceding period. The Molotov-Ribbentrop pact merely sealed the deal. And yet they accuse Trotskyists of being agents of fascism!

The whole previous period showed that the policy of Stalin was one of self-preservation, of preventing revolution. As Trotsky explained:

“The German-Soviet Pact is a capitulation of Stalin before fascist imperialism with the end of preserving the Soviet oligarchy.” (Trotsky, Statement to Press on Soviet-German Alliance, 1939)

Peaceful coexistence between classes?

The Comintern and the CPGB had tremendous political authority as a result of the October Revolution and the undeniable gains of the Soviet planned economy. Yet Dutt squandered this authority to miseducate and misdirect the workers.

Dutt’s main argument was that the working class should bring down the British government, only to replace it with a new one that can work with the Soviet Union to draw up a peace plan with Hitler.

The British working class, however, rightly saw in Hitler’s fascism a direct threat to their interests. They wanted to fight Nazism.

Stalin’s pact, and its justification by Dutt, sowed illusions in Hitler as a reasonable statesman, and obscured the definite class standpoint he represented.

Fascism is the most extreme, reactionary version of capitalism. Its role is to smash the working class and its organisations. Calls for peace in the abstract were thus reactionary and paved the way for further class collaboration.

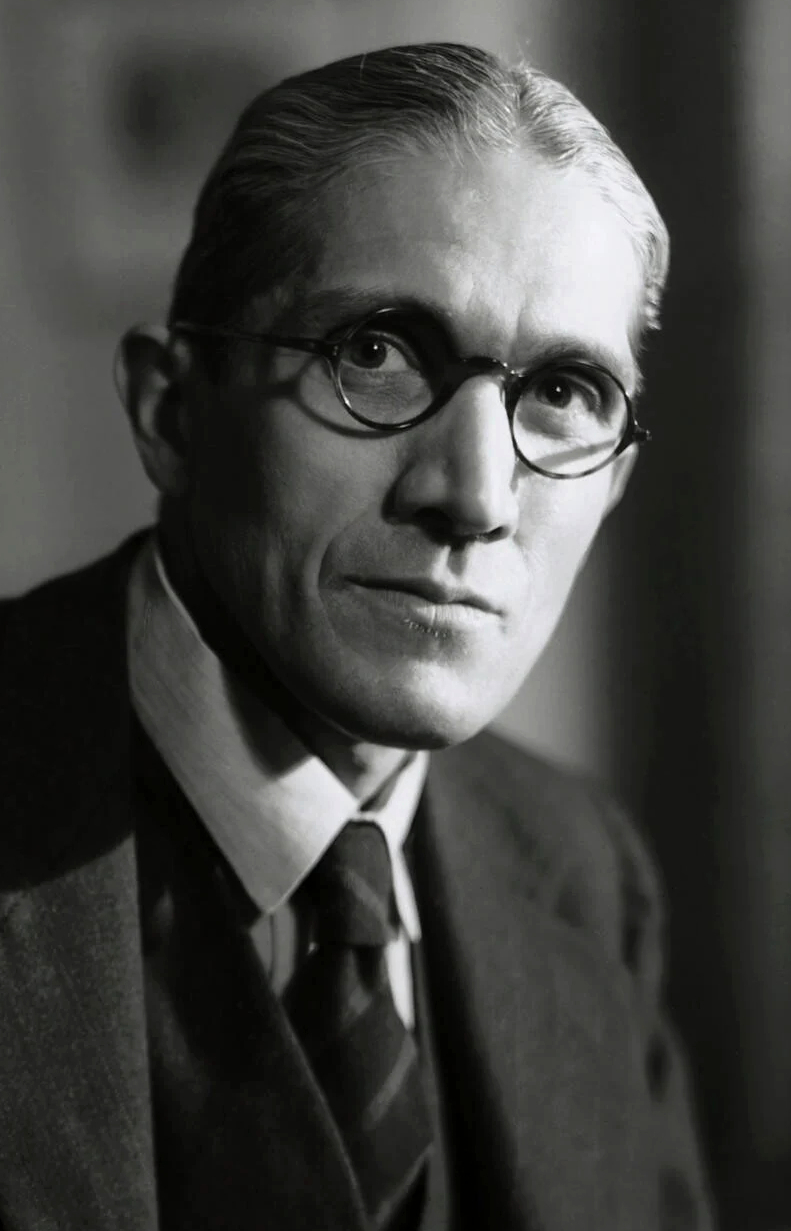

Comrades of the WIL later the RCP advocated for an independent working class programme to fight fascism. Image: Ted Grant Internet Archive (colourised)

Comrades of the WIL later the RCP advocated for an independent working class programme to fight fascism. Image: Ted Grant Internet Archive (colourised)

The alternative was the ‘proletarian military policy’ proposed by Trotsky and developed by Ted Grant.

Its starting point was recognising this healthy desire to fight fascism amongst the working class, and making it clear that the only way to smash fascism is through a revolutionary programme, exposing the capitalists and their appeals for national unity.

As Dutt explains though, the goal of the Comintern wasn’t revolution. It was to replace one set of capitalist crooks with another – one that was more friendly to the Soviet Union.

“Once is tragedy…”

The Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact was yet another striking indication of how deeply the Comintern had degenerated. Substituting proletarian internationalism for diplomatic horse-trading was the embodiment of Stalin’s policy. This method directly led to the Comintern’s downfall: in 1943 Stalin unceremoniously disbanded it to win the support of Churchill and Roosevelt.

The dissolution was signed by the CPGB and welcomed as a necessary and logical step in the fight against fascism. At this stage the CPGB also allied themselves with the same British capitalists it denounced just yesterday.

These actions were nothing less than a complete betrayal of the working class.

Over 80 years later and the CPB (a splinter group from the CPGB which considers itself the CPGB’s successor) still hasn’t learned any of the lessons of this period. As recently as 2021, the CPB’s youth wing, the Young Communist League, republished a defence of the pact.

The role of building up the revolutionary forces during World War Two fell to Ted Grant and the Worker’s International League, and then the Revolutionary Communist Party.

In the RCP today, we continue this legacy of genuine, revolutionary, communism.

Facebook

Twitter

Reddit

WhatsApp

Messenger

Email

Print