Haywood Stenton Jones wanted only the best for his son. “David has no doubt told you that he has been in showbusiness since he was about sixteen and during that time he has learned to take hard knocks and disappointment,” wrote Mr Jones of 4 Plaistow Grove, with the mix of concern and pride typical of a suburban father whose talented child is chasing an unlikely dream. The reference letter was sent to one WA Freshman Esq, head of a Mayfair legal firm, some time between 1964 and 1966.

From a little terraced house in Bromley in Greater London, close to a railway station offering a direct line to Victoria and an escape from postwar provincial dolour, Jones painted an image of a smart young man who needed a little help to get going. “Whenever he takes on an idea of any kind he never lets up and he puts everything he has got into it,” Jones continued, asserting that his son “will be a good ambassador for your organisation”.

Haywood never got to see if David would be a good ambassador for WA Freshman or anywhere else. “He died at just the wrong damn time,” Bowie told fellow Bromley boy Hanif Kureishi in 1993, of a father whose job as head of PR at Dr Barnardo’s brought him into contact with the celebrity world. On August 5, 1969, three months before a 22-year-old Bowie broke through with Space Oddity after years of trying, Jones died of pneumonia at 56.

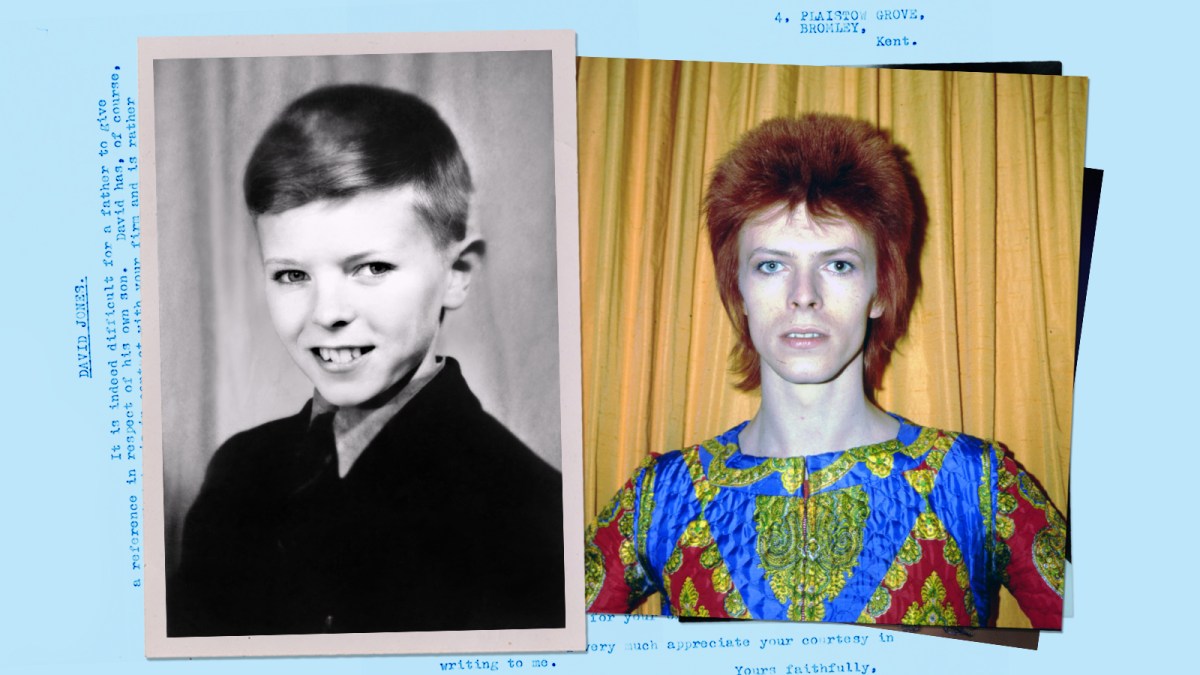

Bowie with his parents; and in 1965

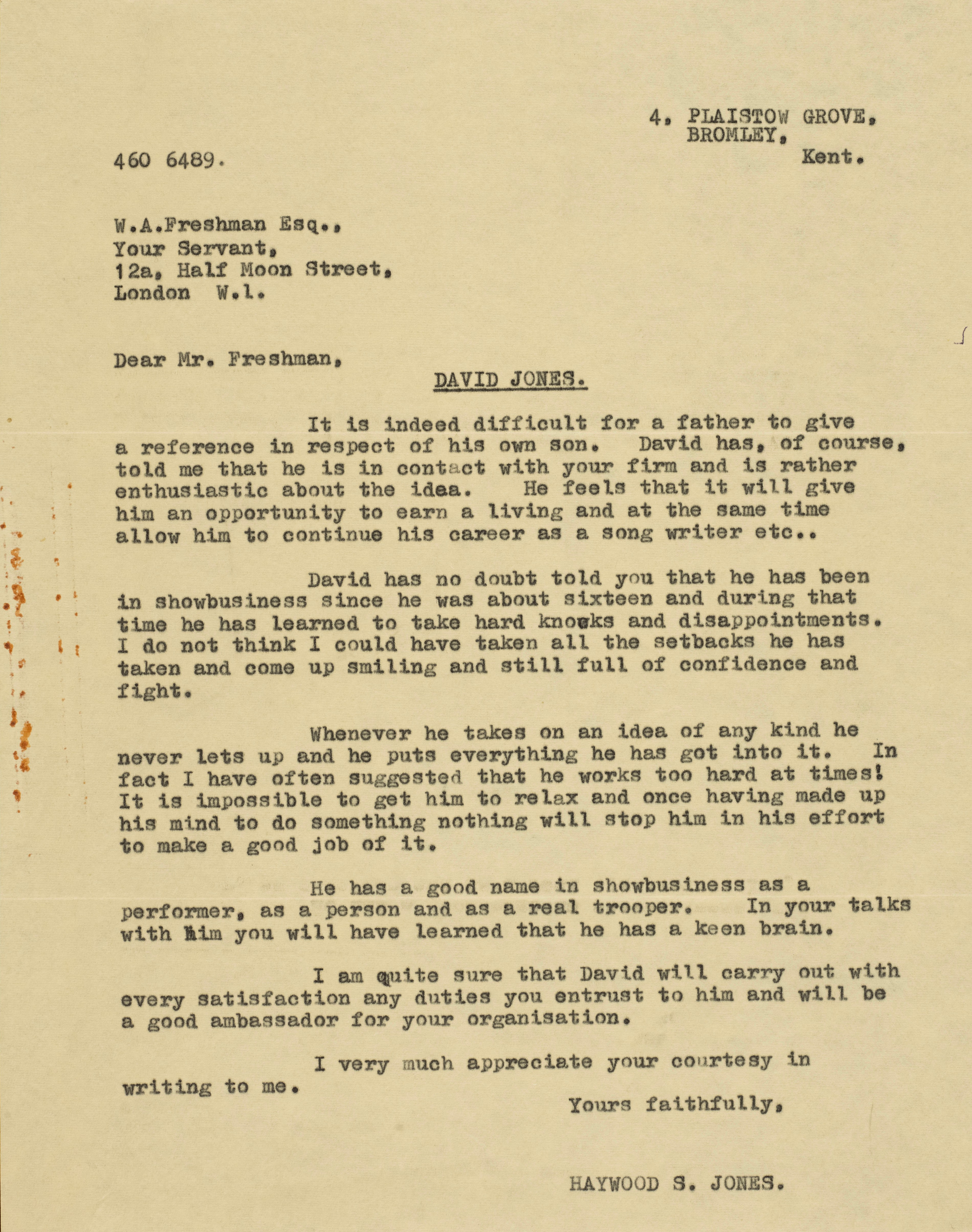

A reference letter by his father

THE DAVID BOWIE ESTATE/V&A, ALISDAIR MACDONALD/GETTY IMAGES

As Bowie’s childhood friend Geoff MacCormack told Dylan Jones in David Bowie: A Life: “His dad was lovely, a really nice gentle man. His mum, well, even David didn’t like his mum.” So Bowie was left with his difficult mother, Peggy, his much admired elder half-brother, Terry, descending into schizophrenia, and the drive and determination that is so often fuelled by early grief.

As it turned out, the legal profession’s loss was showbusiness’s gain. The future David Bowie’s “keen brain” (Haywood’s words) served him well without the patronage of Mr Freshman. And remarkably, as if he knew that one day he would be a figure of great historic importance, Bowie kept everything.

• He fell to Earth: how David Bowie dealt with a decade of obscurity

“We’re showing the letter from his father, alongside one of the first rejection letters he received from Apple Records,” says Madeleine Haddon, curator of the David Bowie archive. This vast collection of more than 90,000 items has been bequeathed to the V&A East Storehouse, a new permanent home in east London for the Victoria and Albert Museum’s collections, which is free to visit. It builds on the success of the V&A’s 2013 Bowie show, which had record ticket sales and went on to tour the world.

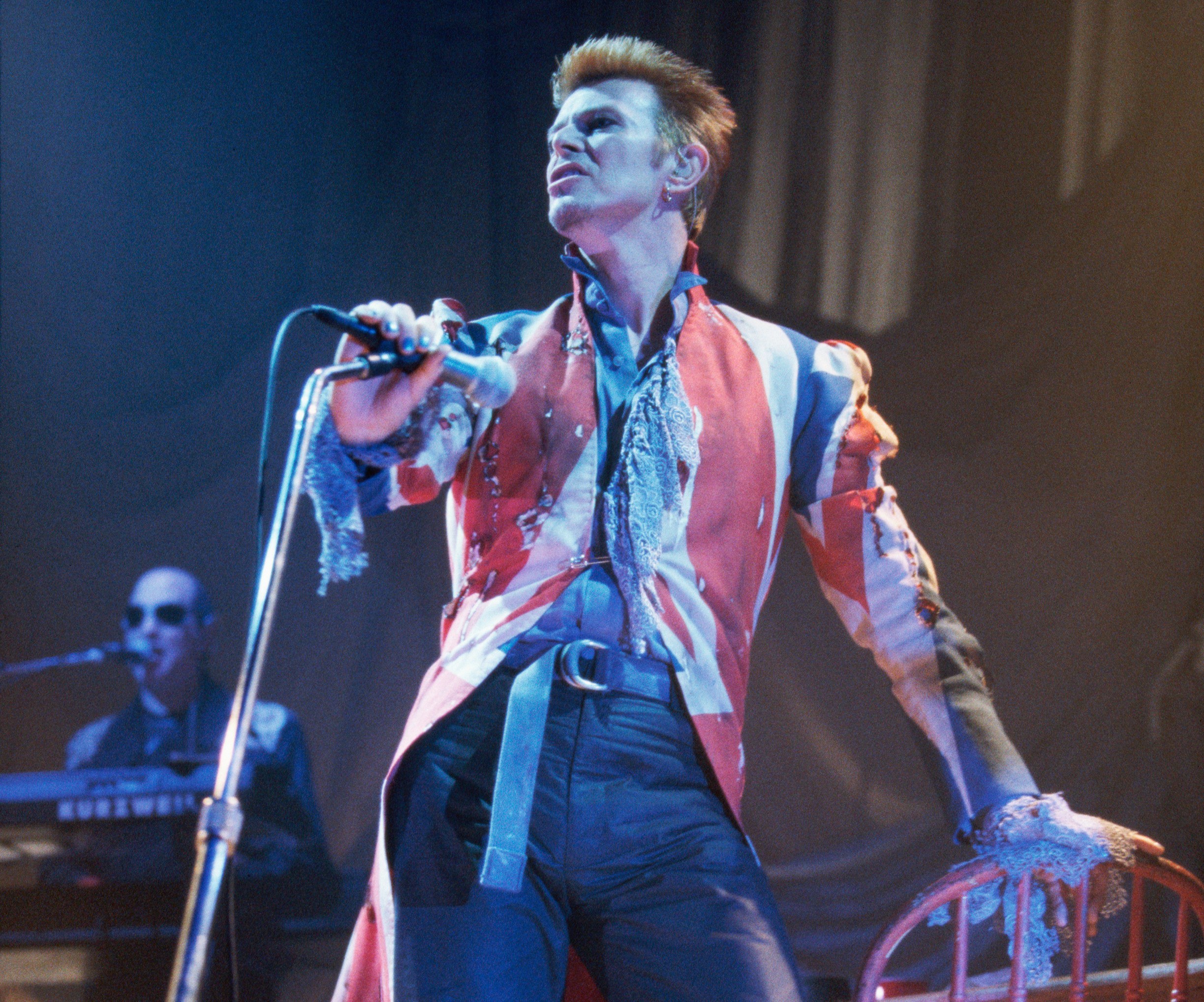

Space oddity: Bowie in concert at Roseland

MITCHELL GERBER/GETTY IMAGES

“The rejection letter states that he was just not what they were looking for right now. It speaks to his perseverance that he wasn’t deterred by these rejections, or by his father having to write on his behalf. Creative geniuses aren’t formed overnight.”

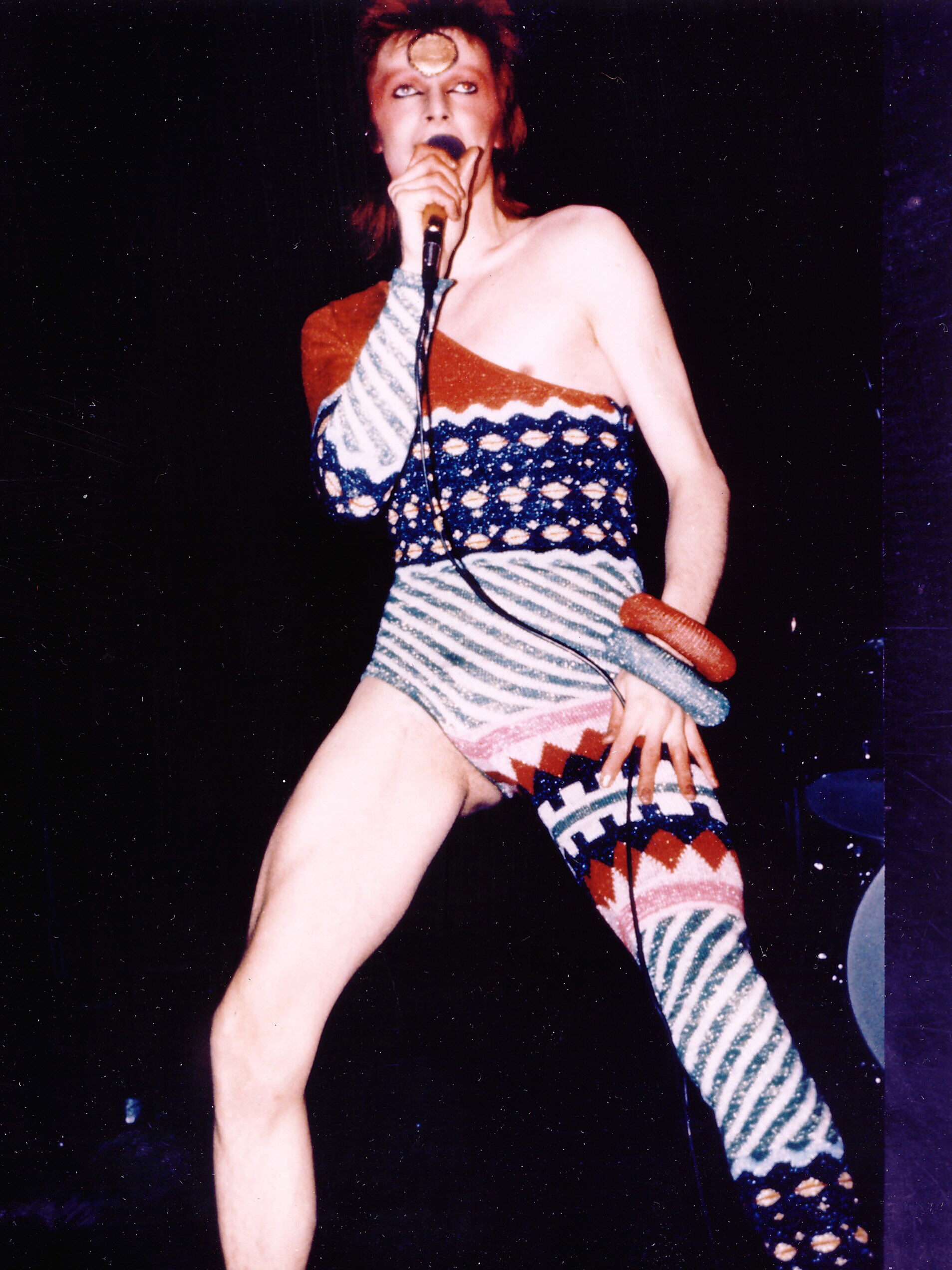

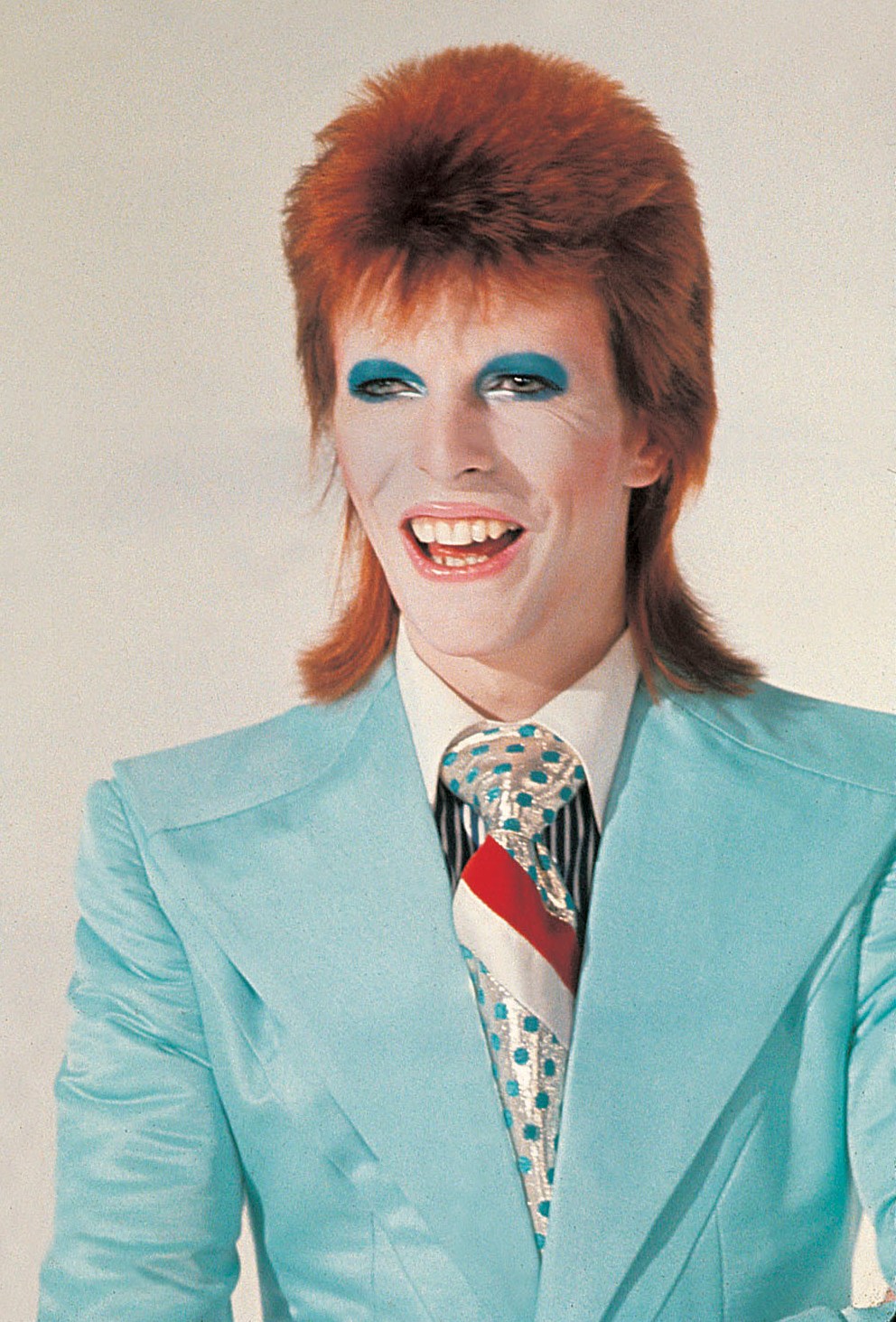

The David Bowie archive exists as concrete proof that Bowie had a curatorial mindset from the start, which included recognising the value of his outrageous stagewear. There are 400 items of clothing, including an ice-blue suit by Freddie Burretti that he wore for the 1972 video for Life on Mars? and a rabbit-print bodysuit made by the Japanese designer Kansai Yamamoto, worn during his 1972 Ziggy Stardust concert at the Rainbow Theatre, London.

“He was a Capricorn: incredibly organised, very good at thinking in patterns,” says Daphne Guinness, fashion designer, singer and scion of the aristocratic Guinness clan. Bowie met Guinness over lunch with his wife Iman in 2010, attended an exhibition of her couture collection at the Fashion Institute of Technology in New York in 2011, and asked her to give a filmed interview on his costumes for the V&A’s David Bowie Is… exhibition of March 2013.

“It was only when we were filming that I realised: I didn’t actually know much about his fashion sense,” Guinness confesses. “He couldn’t have minded because he asked me to do another interview, and that’s when I realised. Most big stars are only interested in themselves. Bowie really was curious about other people and their worlds. He knew I had been close to Alexander McQueen [the designer made Bowie’s Union Jack coat, worn on the cover of his 1997 album Earthling] and he wanted to know more. He was unusual in that way.”

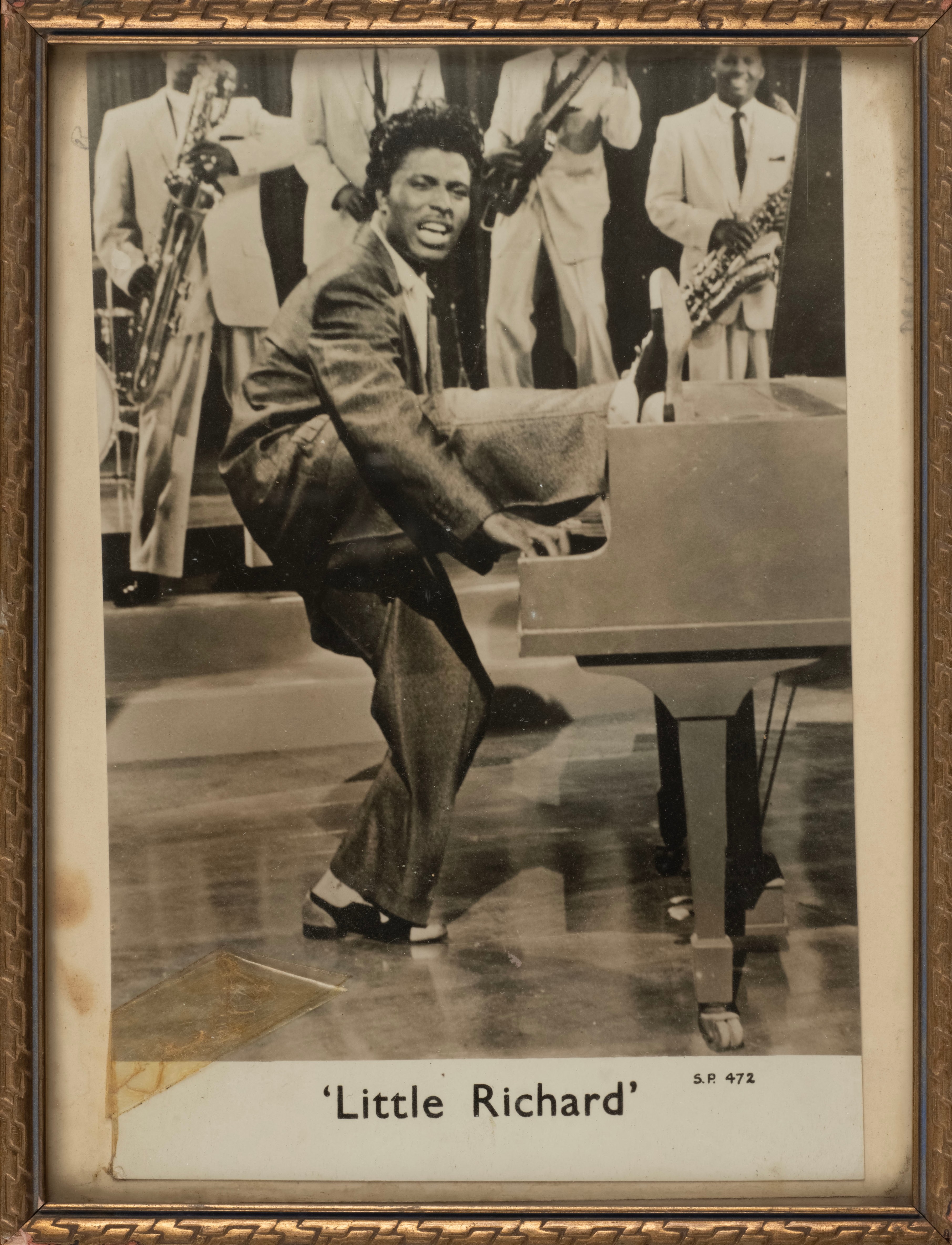

Bowie’s art collection is in there, bequeathed to the V&A by Iman. There are countless fan letters, and a framed black-and-white photograph of Little Richard, leg up on the piano in full performance frenzy, partially mended with tape. Bowie described the photograph as his most treasured possession.

Bowie with Iman…

KMAZUR/WIREIMAGE/GETTY IMAGES

… and his photo of Little Richard

THE DAVID BOWIE ESTATE/PHOTOGRAPH BY V&A

“I sent away for a photograph of Little Richard when I was seven years old,” he said in 1991, of a portrait he kept on his piano from house to house and through decade to decade. “It was called Star Pic. It took eight weeks to arrive and when it arrived it was torn … I was absolutely heartbroken.” Bowie even learnt the saxophone in the hope of joining the rock’n’roller’s backing band. He never got the gig.

All this gives insight into not only Bowie’s inspirations but also his ambitions, his process, his impact, his mindset. And frankly, the vastness of the archive is overwhelming, not least because Bowie kept fan letters, fan art, notebooks, correspondence … even scraps of paper with to-do lists. “Bowie said it was the duty of the archivist to preserve other people’s creativity, not to judge but to care for,” Haddon says, as we look on to the vast space at the storehouse that, on a sunny morning in July, is still under construction. “We have letters around different projects — including the ones that didn’t happen.”

• On the trail of David Bowie — and his favourite haunts

For a figure associated with pushing the limits of transgression, Bowie was remarkably methodical. On a handwritten chart from 1966 he plotted a graph of various potential projects, including a “contemporary soundtrack” for the classic silent movie Metropolis and an unrealised musical theatre concept called “Boy with Sphere”. In a diary entry from 1975 he details the recording of Fame, from his “plastic soul” album Young Americans. “My first co-written [sic] with Lennon, a Beatle, about my future,” he writes of the song. “I thought of films with Lennon. Lots of prospects. Am happy.”

One person to witness this level of documentation and organisation up close was Mike Garson. The classically trained, Brooklyn-born pianist first worked with Bowie on the Ziggy Stardust US tour of 1972, gave the 1973 album Aladdin Sane its unsettlingly discordant jazz solo, and went on to be a staple of Bowie’s live band, right up to the final tour of 2003.

Aladdin Sane contact sheet

© DUFFY ARCHIVE & THE DAVID BOWIE ARCHIVE

“In the mid-Nineties I went to David’s office in New York, when his assistant opened a closet to reveal 20 or 30 enormous hard drives. He had recorded every single show from our Earthling tour,” Garson remembers. “David had an eternal sense of organisation, and yet he still allowed for the freedom. That’s how he managed to pull the best out of you — whether it was Rick Wakeman’s piano on Hunky Dory, Mick Ronson’s guitar on Ziggy Stardust, or me on Aladdin Sane — and absorb it into his own style. It was a strong internal sense that made him special.”

Nonetheless, Bowie was still just a person. A list of ideas for the 1976 album Station to Station, the psychically tormented product of an era when Bowie was subsisting on a diet of milk, peppers and cocaine in his darkened LA apartment, features words like “Harmony, Integrity, Birth, Anger, Love, Peace”. He did a similar one for his album The Next Day in 2013, although it took on the rather more mundane tone of a to-do list: alongside “comparison Woodstock” and “bite worse than bark” are reminders like “haircut” and “clothes for sally army”.

• David Bowie, Madonna and more — the lives of nine famous bisexuals

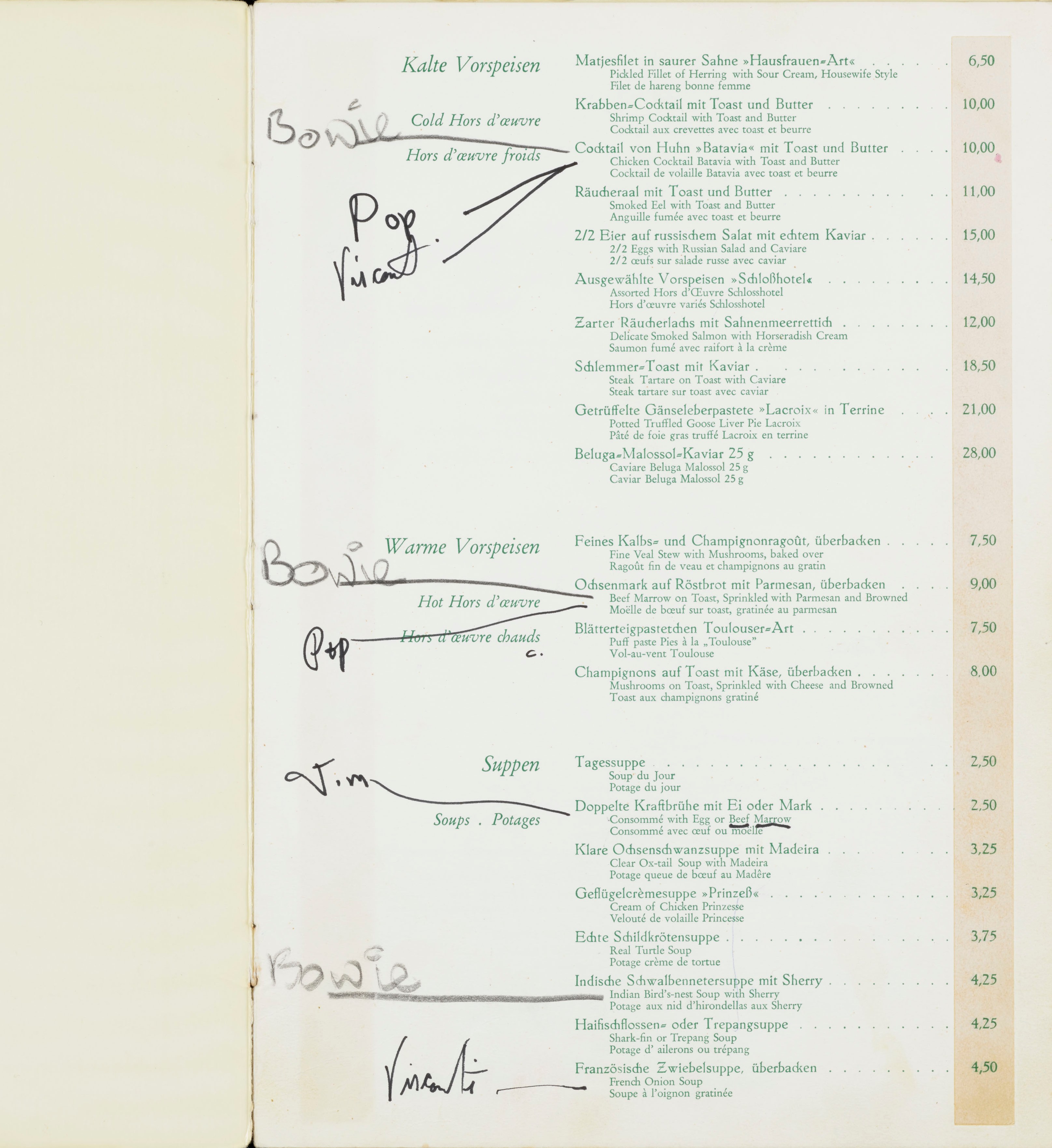

Then comes a menu from a Berlin restaurant that Bowie, Iggy Pop and the producer Tony Visconti visited in 1977, which features handwritten annotations indicating who had what. Bowie obsessives will be interested to learn he went for something called a chicken cocktail Batavia, followed by beef marrow on toast and the distinctly unappetising Indian swallows’ nest soup with sherry. Bowie and Visconti were working on Heroes at the time, soaking the tension of a divided city into that album.

An annotated Berlin menu

THE DAVID BOWIE ESTATE/PHOTOGRAPH BY V&A

“Berlin was dark and people didn’t want to live there,” says Visconti, who went for the more conventional option of French onion soup, a steal at 4.5 marks. “That’s why apartments were so cheap, and David was renting a three bedroom apartment for next to nothing. If you travelled by car from East to West Germany, you couldn’t even stop for petrol. You had to make sure you had a full tank because if you stopped you got shot.”

One of the most revealing letters-to-self in the archives comes from 1998. Over a few pages of lined paper, Bowie muses on the future of music distribution (“The contents of a record store on a handful of CD Roms” — as it turned out, the contents of a record store would actually be on our phones and laptops), the reason why Oasis were yet to break America (“swearing fighting and doing drugs are de rigueur”), and reflects on his place in the pantheon (“I feel closer to [the academic] Marshall McLuhan than to Robbie Williams”). What really fascinates in this stream of consciousness, however, are Bowie’s highly astute thoughts on where the internet would take us.

As Ziggy Stardust in 1970…

WENN

… and in the suit by Freddie Burretti for the 1972 video of Life On Mars?

MICK ROCK

“Valuations of portals will drop. Content will win,” he predicts, correctly. Mapping out BowieNet, the internet service provider he set up in 1998, he plans: “V lean. Handful of employees. No aspirations to make a billion.” A year later Bowie conducted his now famous Newsnight interview with Jeremy Paxman in which he predicted the internet would disrupt everything, cause fragmentation of cohesive thought, and lead to a disintegration between artist and audience. “We’re on the cusp of something exhilarating and terrifying,” he announced to a clearly sceptical Paxman.

The interview was the idea of Alan Edwards, Bowie’s PR from 1983 until his death in 2016, and it came two years after a legendary encounter in which Paxman had asked the former home secretary Michael Howard the same question 12 times in a row. For that reason, Bowie’s initial response to Edwards consisted of the words: “Are you f***ing mad?”

“He also told me that if it went wrong I was fired,” Edwards remembers. “It was a big risk. We found out that Paxman liked fishing, which of course David knew absolutely nothing about, so just before David went on we made sure he happened to have a couple of fishing books on the table.

• Read more music reviews, interviews and guides on what to listen to next

“Paxman’s eyebrows went up, they had a little chat about salmon season or flying fish or something, and suddenly they were best friends. That was typical of the incredible detail and preparation David would put into everything, interviews included. It made working for him a real challenge, but hugely rewarding. You knew you were dealing with a genius.”

As extensive as the David Bowie archive is, it cannot contain everything. In 2018 a wildfire destroyed Mike Garson’s home and studio in Bell Canyon, California, but his wife did manage to grab a charcoal portrait that Bowie drew of him during the Outside tour. “It was really very good,” Garson says. It wasn’t just the legal world that lost out on Bowie, it seems; it was portraiture too. His father would have been proud.

The David Bowie Centre opens at V&A East Storehouse on Sep 13. Access is by free ticket that must be booked in advance. Free tickets go live from Sep 2, and new ticket releases will be available every six weeks thereafter; vam.ac.uk/east