This past spring, I found myself reading books by authors I admire that explore where the collection of artifacts becomes theft and why we are so compelled, pack rats all.

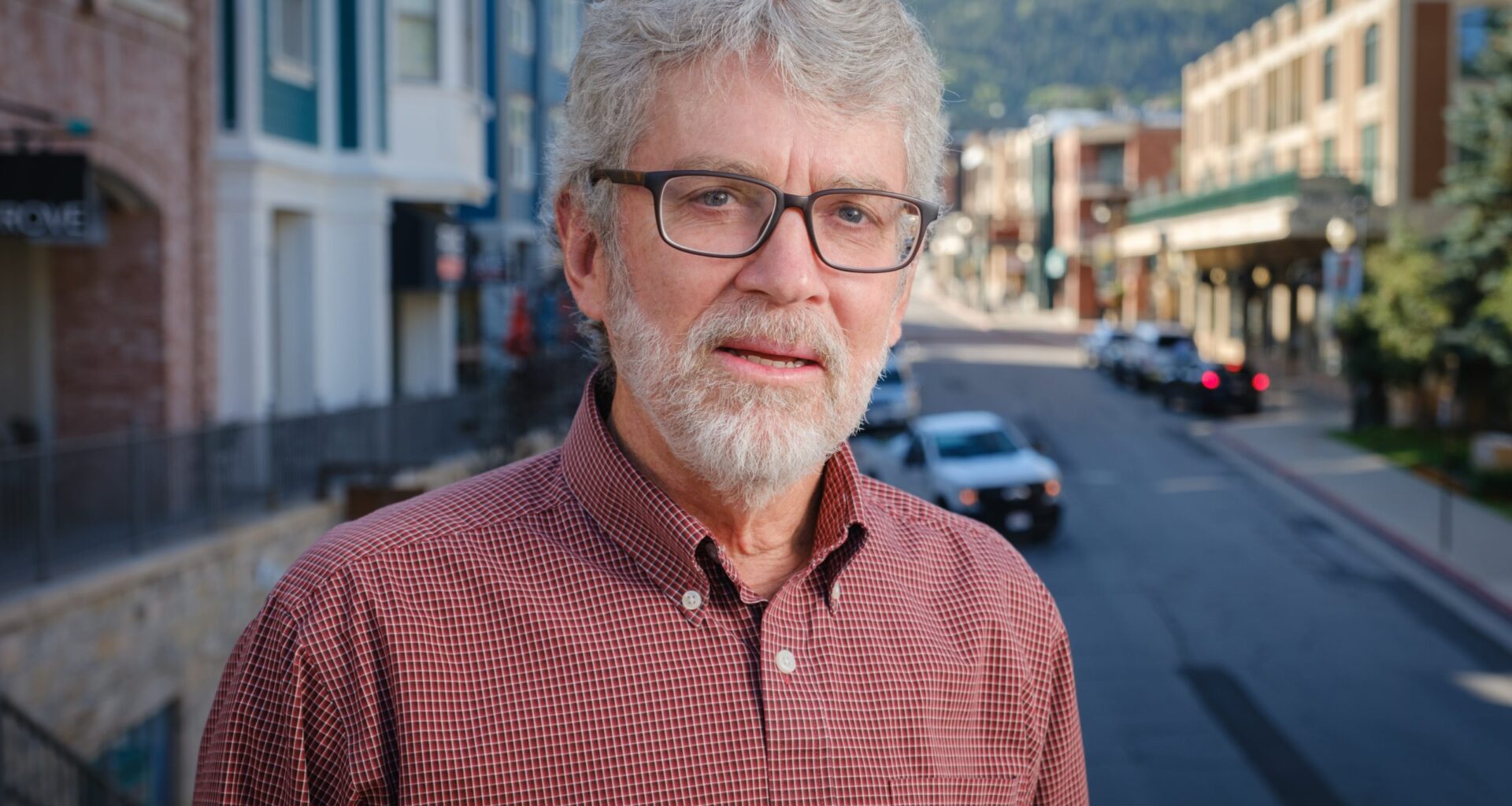

One was written largely in a second-floor office on Main Street: “The Art Thief: A True Story of Love, Crime and a Dangerous Obsession,” by Park City resident Michael Finkel. The other is “Finders Keepers: A Tale of Archaeological Plunder and Obsession,” by Craig Childs.

Bonus for me, I got to meet both while I was reading their books.

Finkel, like his work, snapped and popped in person in a wide-ranging conversation, well punctuated with laughter, that extended through a couple of Main Street bars one quiet off-season night.

Childs glided and sailed along smoother currents, also matching his writing if not so much the western Colorado desert where he lives. The venue was much different, too, a Torrey House Press writing workshop he led at the Cable Mountain Lodge just outside Zion National Park.

My timing with the pair of books was coincidental. Wasatch County reporter Clara Hatcher had noticed “The Art Thief” in my office bookshelf and told me how much she loved the story about this guy in France and his girlfriend lifting $2 billion worth of medieval artwork from museums for their own private collection in the attic bedroom they shared in his mother’s home. You have to read it, she said, eyes alight.

I’d been reading and rereading several of Childs’ books as homework before and after the workshop. Alas, I still haven’t gotten back to my first and favorite, “The Secret Knowledge of Water,” which I stumbled onto while living in Colorado much like I had discovered Edward Abbey’s classic, “Desert Solitaire,” so many years before that. I’ve likened the two ever since, rationally or not. They just give me, I dunno, the same feeling about the Southwestern expanses, their musings, the adventures out there. Kin, then, if not directly related. And Childs is sane. I think.

“Finders Keepers” is mostly about the various ways modern people have raided the ruins of the old ones who were long gone by the time the Navajo arrived. It wasn’t long before we of the European cultures emptied everything we could find out there, filling museums, university archives, private homes and public places like hotel lobbies with Puebloan loot. Childs looks around the world at our predilection for pilfering like this, but mainly focuses on his home desert and his own choices.

In this book he is fascinated with our instinct to take and keep, along with how hard it can be to leave discoveries in situ. Where and, really, why do we draw lines between archeologists with their twine and trowels, and a Blanding ranch family on an after-church potsherd and arrowhead hunt? Lost in a drawer or displayed in a case, the result is no different.

Finkel is focused on one young man’s compulsion to steal specific artwork from museums across Europe. When the mood sweeps over the guy, out comes the Swiss Army knife, his girlfriend as lookout, and a spectacular gift for improvisation while escaping notice. They aren’t caught for years because he’s so good and because he doesn’t steal to sell, only for them alone to enjoy.

Childs writes with understanding of the lure, having pocketed little relics while a child exploring. But he’s long since shifted to a kind of catch-and-release with his hunts.

“I have my own private collection that spans the American Southwest in its tiers of canyons and sharp-sided mesas,” he writes. “A gray ceramic olla lies upside down like a helmet in Arizona beneath a needle-tip peak, and 300 miles away in a cave a pair of Apache water baskets are seated in a nest of wood rat droppings. A painted clay canteen rests on its side under a sandstone band shell in southeast Utah, one horizon north of a red seed jar off in the shade of a boulder.”

He deals with the itch this way: “My pursuit of artifacts has so far been my business alone, a preoccupation with discovery and antiquity, and the least I could do after I found them was leave them be.”

Never mind obsession, Frankel shows no interest in having for himself what ruined his subject, Stéphane Breitwieser’s life.

But I would say, like Breitwieser in the book, he is obsessed with his own urge to collect as well as picky about what he takes. Fenkel is a writer who seeks the marvelous story to match his talent, especially in his books. One is about a murderer who stole his identity, “True Story,” which was made into a movie starring James Franco. Another, “The Stranger in the Woods,” is about a man who lived alone in a tent in the Maine woods and spoke to no one for nearly 30 years. Frankel read something in a local paper and got him to talk just enough to develop a best seller.

No elevating the everyday, as the comparatively droll work of the ski town paper demands. We’re drag netting for minnows while he pursues the whale, testing the heft of his harpoon, trusting his aim.

By contrast, Childs can make a 10-day bike ride into the desert from Las Vegas fascinating, as he does in his most recent book, “The Wild Dark: Finding the Night Sky in the Age of Light.”

While our differences (and talent levels) abound, we do share as writers an obsession at least as powerful and addictive as any Mona Lisa or untouched kiva burns for such treasure moths. Childs and Finkel’s sheer curiosity on the page alone makes this clear.

Part of this is the hunt itself. The other part is the collecting. In a tangible sense, we writers wind up creating our own artifacts, which are just as real as a medieval masterpiece or intact jar left undiscovered for many centuries in the desert.

Our pieces may be shared for the ages if they turn out to be profound enough, another Tolstoy or Hemingway or Morrison, say. But really, our assemblages of wisdom or wit or something else are ultimately for ourselves, our own touchstones — proofs of our time on Earth for someone else perhaps someday to collect in their own grasp for eternity or whatever it is that attracts so many of us to bright and shinies from antiquity.

Don Rogers is the editor and publisher of The Park Record. He can be reached at [email protected] or (970) 376-0745.

Related Stories