Editor’s note: This story is part of Peak, The Athletic’s desk covering leadership, personal development and success through the lens of sports. Follow Peak here.

It was a little before 11 p.m. on the last day in May when Michael Phelps texted a friend.

“Went to a dark place today….Going to bed now…just wanted to keep you in the loop … love ya homie”

Within the hour, Jay Glazer, Fox’s NFL Insider and a longtime MMA trainer, texted back:

“I love you for telling me! Need to talk?? I can if you need. PROTECT YOUR FORTRESS!!! You deserve to protect yourself. I f—— love the s— out of you!!! Call or Facetime if you need, I’m here for ya”

Phelps and Glazer met 13 years ago, when Phelps, the most decorated Olympian in history, was still chasing gold medals in the swimming pool. But they reconnected in 2022, bonded by a shared history with anxiety and depression. Their long conversation about their similar struggles soon turned into steady text updates, FaceTime calls and video messages.

“We’re lifelines for each other,” Glazer said.

As the friendship bloomed, the two realized their bond had become a source of strength, a simple way to reframe their thinking during depressive episodes and anxiety attacks.

They wanted others to experience that kind of connection, too. What started as a small group chat sprouted into a loosely connected community of athletes and celebrities who lean on each other in different ways. Phelps calls the network his “mental health buddies.” Glazer has another term: “battle buddies.”

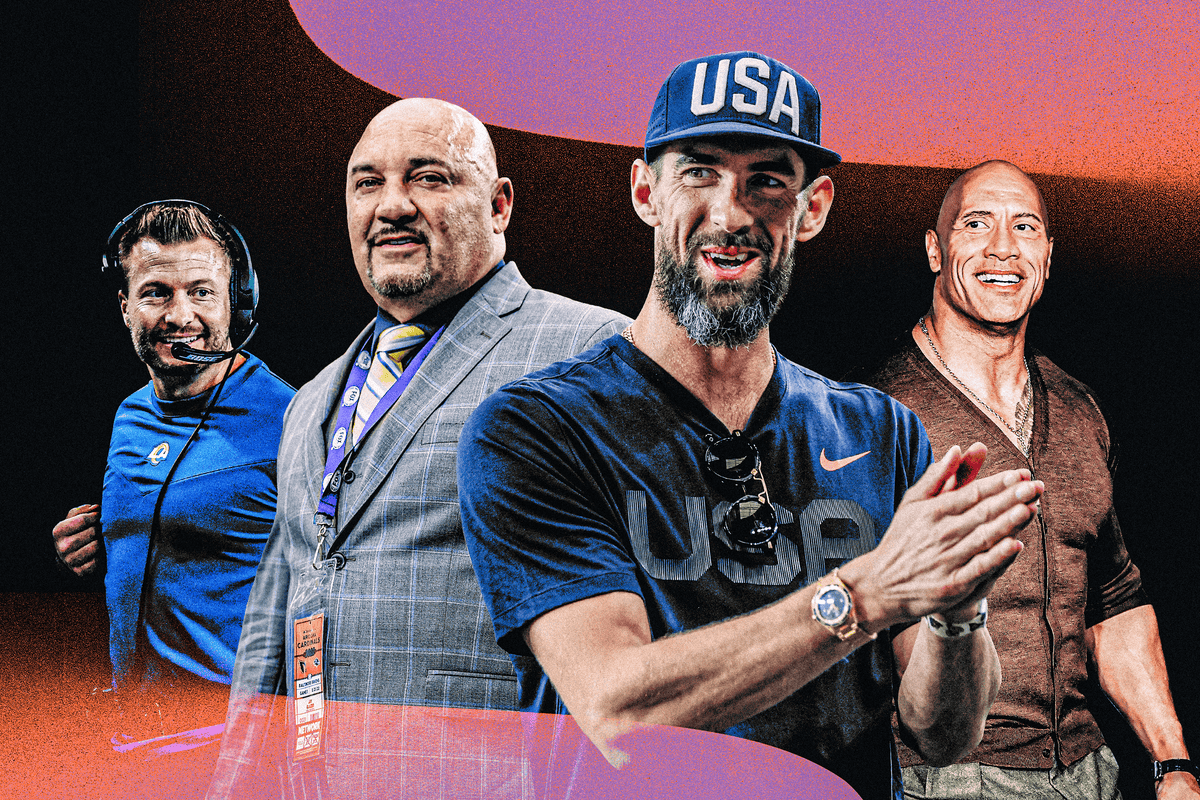

The sprawling roster includes everyone from NFL head coaches Sean McVay and Dan Quinn to former Pro Bowl offensive tackle Andrew Whitworth to UFC Hall of Famer Mark Kerr to The Rock — as in professional wrestler and actor Dwayne Johnson.

“These are some of the baddest dudes on the planet,” Glazer said.

And yet they have cried and vented and let each other in during their hardest and darkest moments.

The check-ins are constant. One day earlier this month, Glazer was in the midst of a long road trip to visit NFL training camps, which meant he was out of his routine. McVay called to make sure he was good. Phelps reached out three times the first week. Johnson touched base twice.

“What I’ve realized is when you show up for your friends, not just when times are good but when s— goes sideways, it also allows you to show up for yourself,” Johnson told The Athletic. “It’s like this alchemy that happens. You begin to become a little bit stronger, and you begin to get your emotional calluses. And you begin to learn how to deal with things.”

The earliest origins of the “battle buddies” started in an unlikely place: A Subway commercial.

Phelps was starring in a series of ads in the lead-up to the 2012 Olympics in London. His comedic foil for the ads happened to be Glazer, the gregarious NFL reporter who moonlighted as an MMA trainer for athletes and celebrities. The two formed an easy friendship and stayed in touch.

Three years ago, Glazer invited Phelps on his podcast, where they opened up about enduring many of the same mental health struggles: feelings of isolation, negative thoughts, sudden impulses to harm themselves.

They stayed in contact, reaching out when either started to spiral, realizing they weren’t always looking for words of encouragement or advice or even reciprocity, just someone to listen.

“Never once have we felt ashamed,” Glazer said. “Never once have we regretted sending.”

“I can go to him and f—– say absolutely anything,” Phelps said. “I’m not going to be judged. That’s how it should be.”

Sometimes all they need is a text or a quick reminder. Phelps came to see his mind as a television. If he didn’t like what he was watching, he needed to change the channel and take a deep breath. Glazer helped him do that.

“We’ll kind of coach each other on what to do,” Glazer said. “Like, ‘Hey, you’re being manic. This doesn’t make any sense, right? Look at it this way.’ And we never get angry at each other if we call it out.”

Glazer started to see the contact as a ritual. One day, he proposed another one.

“Should we open this up to other brothers or other people like us that are struggling?” he asked Phelps.

“F— yeah, why not?” Phelps said. “This is awesome. Let’s form a community.”

Andrew Whitworth and Sean McVay developed a close relationship during Whitworth’s time with the Rams. (Kevin C. Cox / Getty Images)

Glazer was already confiding in and supporting a small group of friends from NFL circles. One day, he added one to a group chat with Phelps: Whitworth, who had recently retired after 16 seasons.

“When you get out of the game, you get away from each other,” Whitworth said. “You kind of live life for those people. There is this relationship and bond that is a daily rhythm to your heart, your soul. You get removed from that, and you start to fill it with emptiness or thoughts of loneliness.”

Whitworth joined in and realized he wanted to keep the group spreading. He shared pieces with McVay, his former coach, and Reggie Scott, Los Angeles Rams vice president of sports medicine and players he’d befriended in the league, like Travis Kelce.

“The more people that we got in, the more comfortable I felt,” said Phelps, an ambassador for the online therapy company Talkspace. “The more safe, protected. When we are in that dark place, we feel like we’re all alone. We feel like nobody understands us. So it’s really cool to have a handful of shoulders — like a dozen shoulders — to reach out to at any given moment.”

Though no one in the group is a mental health professional or has had training in the field, their personal experiences have allowed them to build a community. More than that, it’s tapped into a transformative idea: People often underestimate just how much they will enjoy deep conversations with other people.

“Not because they fail to appreciate that having a meaningful conversation is something that they will enjoy personally,” said Nicholas Epley, a professor of behavioral science at the University of Chicago. “But because they underestimate how positively other people will respond to it. We underestimate how much power we actually have to make ourselves and other people feel better — notably better — by connecting with them.”

Glazer wasn’t always ready to open up.

One night three years ago, he was supposed to go to dinner with Michael Strahan, the former New York Giants star and television host. They had been friends since 1993 — at one point, carpooling into New York City for years — but Strahan knew little of Glazer’s struggles.

Before dinner, Glazer felt the familiar symptoms kick in: Pain in his left side, behind his ribcage; a weight on his chest, which felt like “having a heart attack.” And a heavy soreness in his joints, which he compared to a “50-round fight in the rain.”

In the past, he would respond by taking Vicodin and drinking alcohol.

“I’d rather put my life and job on the line than let anybody know I really had this depression and anxiety,” he said. “This shame.”

But for the first time, Glazer explained to Strahan what was happening.

“The beast got out of the box,” Glazer told him.

Strahan offered to come over, then asked, “Why have you never told me?”

“Dude, I was ashamed,” Glazer recalled saying. “I was ashamed because you and I are so competitive, we’re brothers.”

“Yeah,” Strahan said, according to Glazer. “But you took away my chance to be your best friend for 30 years.”

That moment helped him realize people want to listen.

Michael Strahan helped Jay Glazer understand that people want to help and support others. (Jason Miller / Getty Images)

Before Dan Quinn returned to the NFL as head coach of the Washington Commanders, he had been fired by the Atlanta Falcons during the 2020 season.

“I went from somebody that was trying to give the encouragement, and then all of a sudden in 2020, I’m the one that needed it,” Quinn recalled.

Within 48 hours, Glazer told Quinn that he needed him to hop on a Zoom call. Secretly, he had coordinated for 50 of Quinn’s former players, coaches and friends to be on the call. The Zoom call lasted for over an hour, as everyone took turns sharing how Quinn impacted their lives.

“It was overwhelming, honestly,” Quinn said.

“He cried his eyes out,” said Glazer.

After that day, Quinn continued to lean on Glazer.

“It didn’t mean he had to fix it,” Quinn said. “He’s like, ‘Just call me.’ And so I did. It just helped having somebody to talk to on a random Tuesday at 11 in the morning. Especially when for the last 25 years of my life, I knew exactly what I was doing that day at 11 o’clock, and then didn’t.”

Those calls affected Quinn so much that he eventually started reaching out to other fired coaches because he knew how much it had meant to him.

Late in 2022, Glazer and Whitworth consistently checked in with McVay, the head coach of the Rams. The calls were constant.

McVay was in the middle of what he later called the hardest year of his life. Less than 10 months after becoming the youngest coach to win the Super Bowl, he felt lost. The Rams were en route to a 5-12 season, and his identity was so tied to results that each loss only increased his self-doubt.

He knew how to say the right things, to mask the insecurity and the doubt. But he didn’t feel right inside.

“I was a lot more fragile than I’d ever want to admit,” McVay said.

By the end of the season, he openly talked about stepping away from coaching. McVay had bonded with Whitworth for five seasons in Los Angeles. He’d known Glazer for years. The friends spoke on a trip in Mexico the previous year, where Glazer had first brought up “the gray,” the stew of anxiety and depression that always felt a beat away. At the time, McVay didn’t quite get it.

But as he listened to his friends, he internalized a simple message: “You’re not weaker for having shortcomings. You’re stronger for acknowledging them.”

“You can impress people with your strengths,” McVay said. “But you connect with them through your weaknesses.”

Through conversations with Glazer and Whitworth, and connections to people in their network like Phelps, McVay has reframed his view of mental toughness. He has found strength in vulnerability and embraces empathy in ways that trickle down to how he runs his team.

“One of the things that we try to really do here is judge people on their best day, not their worst days,” McVay said. “That’s what I get from those guys.”

The network kept growing.

When Glazer moved to Arizona several years ago, he reached out to his friend Mark Kerr, a former UFC heavyweight champion who went by the nickname “The Smashing Machine.”

At the time, Glazer was in a “really, really dark place.” But he was trying to approach it differently than he had in the past. He believed that leaning on his UFC friends, mentally and physically, would give him a better chance of pulling out of it. So he connected with Kerr.

“I’m going to start training you again to be Mark Kerr,” Glazer told him. “Not the Smashing Machine. Just Mark Kerr. Because I need Mark Kerr. So you can be there for me.”

Kerr had battled addictions to painkillers and alcohol, but had been sober for a few years when Glazer asked him to train.

“I was just broken, but I didn’t realize how broken I was until I got around Jay,” Kerr said. “I built up so much shame about being an addict, being an alcoholic. I ostracized myself from (the UFC) community because I was embarrassed.”

The two put their gloves on in Glazer’s driveway and “shadow sparred,” a fighting technique without any physical contact. Then they threw a few punches. Kerr realized Glazer had worked through a lot of the same struggles in his life. He asked Glazer what he did; Glazer told him he talked to people.

“OK,” Kerr said. “Let’s start talking more.”

Over time, Kerr began to reconnect with UFC friends and developed a deeper relationship with his siblings.

In June this year, Kerr was inducted into the UFC Hall of Fame. The person who introduced him was another point of connection: Dwayne “The Rock” Johnson. Johnson was in the process of starring in an upcoming movie about Kerr. As production ramped up, the two met up in Vancouver at a dinner with cast and crew. Kerr sat close to Johnson and engaged in a deep conversation.

“It was this feeling like I’m the only person in the room,” Kerr said. “He’s so intentional with how he listens that you know he’s absorbing every word, and it’s important to him. He translates to you that you’re important, not because of the movie, just as a person. You’re important.”

From then on, Kerr said, Johnson left him “jaw-dropping voice messages.” Some were simple, uplifting reminders, but they resonated with Kerr. “Just amazing,” he said. “Absolutely amazing.”

“I didn’t allow myself credit,” Kerr said. “And DJ would say to me, ‘Buddy, this is your life. Give yourself credit for it. It’s amazing.’ Through this process, I finally allowed myself the grace to give myself the credit for living a life I’ve lived.”

One morning several years ago, Johnson was on the phone with Glazer.

Johnson was in a funk. His father, Rocky, had died in January 2020, and he was still grappling with how to process it. Their relationship had always been complicated. Johnson knew his dad loved him, but it was tough love. That Christmas, Johnson and his dad had had a big argument, and when Rocky died unexpectedly from a heart attack, they weren’t on speaking terms. Johnson had regrets about that.

Glazer was one of the few people Johnson leaned on, and he offered a simple prompt on the phone that morning: “Tell me some of the good stuff about your dad.”

Johnson and Glazer had developed a close relationship over the previous 15 years, calling and checking in on each other often. Johnson had even stopped production on the set of his movies for 30 minutes so he could talk to Glazer on the phone when Glazer was going through hard times of his own.

“Come up out of the muck, and you can come walk down this road with me,” Johnson would tell him. “Hopefully, I can help you see what I see.”

Now it was Johnson who needed the support, but he wasn’t sure he wanted to open up, not even to Glazer.

“I’ve never been much of a talker in that way,” Johnson said. “I’m not a big therapy guy. I’m an only child, and I grew up in a tough environment with my dad. The idea of talking about your feelings was something that was never present in my house.”

Even though it was unnatural for him, he started to tell Glazer about his dad, a former professional wrestler who was homeless at 13 and whose tough love taught him lessons about hard work and discipline. The conversation forced Johnson to reflect, which allowed him to appreciate the good things his father had done for him, and helped him to crawl out of his funk.

“I’ll never forget that day,” Johnson said.

It’s the kind of connection that Glazer and Phelps envisioned when they opened up their conversations to more people. Each of them, in their own way, has found purpose in those relationships. For Kerr, opening up allowed him to discover a new layer of self-worth. For Glazer and Johnson, helping others helps them. And for Phelps, the connections make him feel less alone and more understood.

“The more that we can keep doing this, and the more that we can keep bringing people into our group, the only thing it’s going to do is create change,” Phelps said. “And that’s all we want.”

(Illustration: Dan Goldfarb / The Athletic; Harry How, Jeremy Chen, Robert Okine, Christian Petersen / Getty Images)