A niche-sounding rule change in Washington could hit thousands of UK SME exporters, raising costs, and cutting off a driver of innovation.

On 29 August 2025, UK exporters will lose access to a crucial enabler of frictionless trade when the USA eliminates its $800 de minimis threshold. Far from being a technical customs adjustment, this exemption has underpinned UK SME exporters’ ability to access US consumers directly, compete globally without high upfront conditions, and drive innovation. Postal services across Europe have already suspended deliveries to the US, cutting SMEs off until US Customs clarifies the rules.

Its removal comes at a time when SME sentiment is already weak, and it continues the broader shift away from open, low-friction trade. Past shocks like Brexit show how disruptive new barriers can be. Businesses will need to adapt quickly, working with platforms, logistics providers, and Chambers of Commerce, while the UK Government will need to accelerate its trade strategy implementation to soften the blow.

A great leveller in global trade

Introduced in 2016, the $800 threshold allows for shipments under that value to enter the USA duty-free. In 2021 alone, goods worth around $5 billion were shipped from the UK to the USA under the de minimis exemption.[1] Around 80% of these shipments came through e-commerce channels, with clothing and fashion accounting for a significant share.

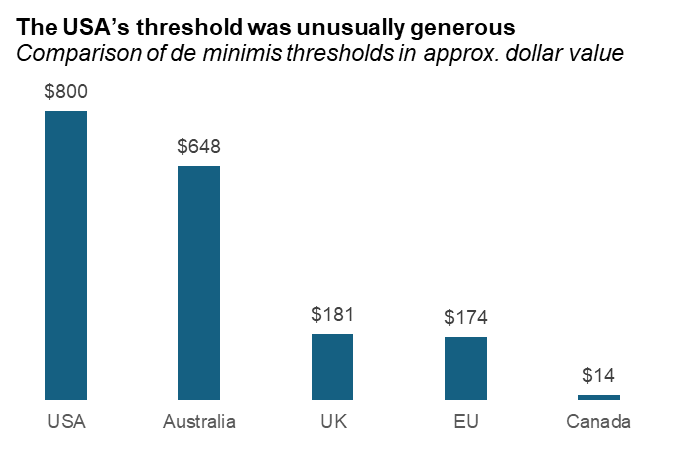

Most parcels were single, low-value items ordered directly by US consumers online. This meant that even the smallest independent sellers could bypass complex paperwork and duties to reach the world’s largest consumer market. By comparison, thresholds set by other countries are far more modest (see below table).

The decision reflects a harder-edged US trade stance, with the administration citing concerns over fraud, unfair competition from foreign sellers, and the desire to boost domestic manufacturing.

An unseen driver of innovation

The USA’s unusually high threshold didn’t just lower costs, it created space for SMEs to innovate. By stripping away duties and paperwork on low-value parcels, it quietly allowed SMEs to act like multinationals – testing products abroad, reaching US consumers directly, and scaling exports through digital channels without prohibitive risk. For smaller firms without dedicated product teams, this mattered hugely: it created space to “learn by doing,” experimenting with product cycles, fulfilment models, and building direct, real-time relationships with consumers.

Evidence from the OECD[2], the Social Market Foundation[3], and other trade economists has shown that de minimis thresholds disproportionately benefit SMEs by reducing fixed trade costs and lowering compliance barriers. The more firms engaged in trade, the greater the spillover benefits for growth and innovation. In effect, it acted as a hidden free-market hand, overcoming the collective action problem SMEs face in accessing global markets.

Is this another Brexit?

The end of de minimis lands just as SME exporter sentiment hits a low. In Q2 2025, only 22% of more than 2,000 SME exporters reported increased export orders, while 27% saw declines, with micro-exporters faring even worse.[4]

Brexit could provide a useful parallel. When the UK left the EU, SMEs suddenly faced trade barriers they had never encountered before. Following the introduction of the Trade and Cooperation Agreement (TCA) in 2021, a BCC survey found that around half (49%) of exporters reported difficulty adapting to the new rules, compared with only 16% who found it easy.[5]

Two main problems stood out: the initial confusion causing backlogs at ports, and then the ongoing burden of structurally higher costs and paperwork built into the TCA. SME responses varied widely – some were caught unaware, others prepared partially, and some completely overhauled their business model. By 2022, 15% of 484 exporters said they had established or increased a commercial presence in the EU as a direct result of Brexit.

The US shift may not be as seismic as Brexit, but a similar pattern is unfolding. The suspension of postal services is a source of increased confusion. But firms accustomed to frictionless exports will now face permanently higher costs. Some may decrease or cease exporting to the USA, and some may even establish a US base to avoid the cost.

A broader shift – and the need to adapt quickly

The suspension of postal deliveries to the US is only the first ripple of disruption, but the removal of the US de minimis exemption is part of a wider global trend toward greater friction of lower-value trade flows. The EU is considering eliminating its own €150 threshold, centralising customs oversight, and introducing a single Customs Data Hub and trader interface. Even the UK may review its own £135 threshold, with HM Treasury projecting up to £1 billion in additional customs duties. EU member states are also set to introduce a €2 charge per item to fund the additional compliance work. Together, these measures could threaten consumer facing exporting sectors, as well as the pipeline of SMEs that may think twice about exporting.

For smaller firms, this all marks increased pressure. Those exposed will need to work closely with distributors, logistics providers, and online partners to mitigate rising costs and ensure reliable product supply. Proof of origin is now crucial, given varying tariff rates across countries. In the short term, exporters will require practical guidance and support to navigate new compliance rules – this is where a relationship with the Chamber of Commerce network is essential. Over the medium and longer term, their ability to compete will hinge on a proactive UK trade strategy which enables stronger supply chains, targeted business support, modernised digital trade infrastructure, and a prioritisation of negotiation not escalation.[6]

As trade friction rises, with the removal of de minimis as the latest example, SMEs will need to innovate, adapt, and forge closer partnerships to maintain their edge in global markets.

[1] https://www.congress.gov/crs-product/IF12891

[2] https://www.oecd.org/content/dam/oecd/en/publications/reports/2021/05/trade-in-the-time-of-parcels_acf1943f/0faac348-en.pdf

[3] https://www.smf.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2025/06/Small-business-big-ambition-June-2025.pdf

[4] https://www.britishchambers.org.uk/news/2025/07/trade-strategy-must-support-smaller-exporters/

[5] https://www.britishchambers.org.uk/news/2021/02/bcc-brexit-survey-half-of-uk-exporters-report-difficulties-adapting-to-changes-relating-to-eu-uk-goods-trade/

[6] https://www.britishchambers.org.uk/news/2025/04/extent-of-us-tariff-impact-revealed/