France installed Ahmadou Ahidjo as Prime Minister in 1958. When French Cameroon declared independence on January 1, 1960, Ahidjo became the first President. The war continued nevertheless, with French forces actively supporting operations against UPC fighters.

Max Bardet, a former pilot who served in Cameroon from 1962 to 1964, has testified to the systematic targeting of the Bamileke people.

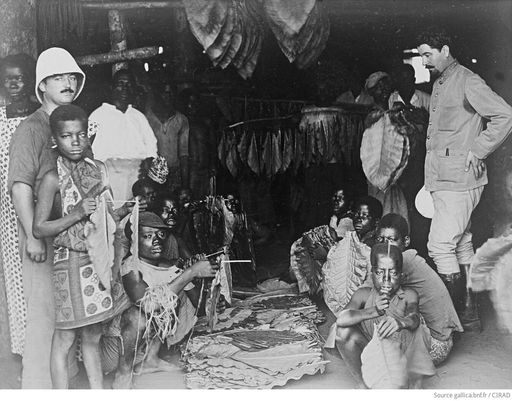

French forces bombed villages, forced hundreds of thousands into internment camps and tortured them. Even women and children weren’t spared. These atrocities were systematically covered up.

Cloaking the truth

France employed elaborate strategies to conceal the war’s atrocities from both the French and Cameroonian public.

Prof Jacob Tatsitsa of the University of Ottawa in Canada has researched and written extensively about the systematic cover-up.

“First, in 1955, particularly after France’s defeat in Indochina, it decided to teach Cameroon a lesson in revolutionary warfare, a set of measures to be implemented to delegitimise the struggle of Cameroonian nationalists,” he explains.

A circular from Roland Pré, who was appointed high commissioner of Cameroon in 1954, prescribed establishing press outlets that would praise the French administration while downplaying the struggle for independence.

As part of the strategy, war zones were closed to journalists. The few who had access were those complicit in France’s clandestine activities.

After independence, the censorship actually intensified, says Tatsitsa.

Anyone found with documents supporting the UPC faced arrest and imprisonment under what were called anti-subversion laws. The censorship extended to France much later, with the book Main basse sur le Cameroun by Mongo Beti being banned for its critical analysis of the situation in Cameroon.

“Nominal independence meant independence stripped of all its substance, because the French infiltrated all positions of sovereignty,” says Tatsitsa.

A divided legacy

The scars of the colonial era continue to fester in Cameroon.

When Southern Cameroons voted in a February 1961 referendum to unite with the Republic of Cameroon (whilst Northern Cameroons joined Nigeria), the country inherited conflicting colonial systems. East Cameroon carried French culture, language, law and education. West Cameroon bore the British equivalents.

“Although the two Cameroons united under a federal system, the distinct colonial legacies they had inherited and sought to preserve gradually became a source of conflict,” says Dr Ibrahim.

The shift from a federal to unitary state in 1972 saw the French-speaking majority – about 80% of the population – impose assimilation policies on the English-speaking minority.

“This problem deepened over time and, by 2016, escalated into an armed struggle led by the Anglophone population demanding full independence. To this day, this externally imported problem has yet to be resolved,” rues Dr Ibrahim.

Even after France’s formal withdrawal, French advisors remained embedded throughout Cameroon’s administration, military and police, supported by local collaborators. The deaths of tens of thousands were deliberately concealed.

Waiting for reparation

While Macron’s acknowledgement breaks decades of official silence, it still rings hollow in the ears of many Cameroonians.

“For Cameroonians, this recognition is belated and incomplete, as the term ‘reparations’ is nowhere to be found in this letter. We are still waiting for an apology and reparations, and then for the archives to be fully opened, digitised and made available to all researchers,” says Tatsitsa.

Dr Therence Atabong Njuafac, who holds a Ph.D. in international relations and political science and heads the organisation Humanity Helping Hands Cameroon, points to systemic collusion for this part of the nation’s history remaining buried.

“Our leaders have strong relations with France, and it seems they collaborate in many ways. France still has a lot to do within the country. Even our currency is being made in France, so you can tell you how connected the two countries still are,” he tells TRT Afrika. “Maybe the masses are angry with France, but not the government.”

Adama speaks about Macron’s letter leaving “a bitter taste” rather than healing. “France does not address the issue of reparation, the issue of justice. It is content to control the narrative and to try to stretch the cover-up on its side.”

But Dr Ibrahim sees this moment as an opportunity. “Following Macron’s remarks, I believe the time has come to revisit the history of Cameroon’s struggle against French colonial rule by turning back to the archives,” he says.

A few critical questions remain unanswered, though. “Will historians and researchers be willing to uncover these archives? And will Cameroon itself allow and encourage such an undertaking?” Dr Ibrahim wonders.

This article was first published on TRT Afrika.