When William was still Duke of Cambridge, before he became Prince of Wales, he showed a degree of carefulness and respect for the constitutional boundaries that had not always been evident with his father when he was the same age. As one source who knows William well said, “He cares about issues but he has made very sure to be apolitical in the way he has done it.”

Michael Gove has had a number of conversations with William about his interests over the years, including about a government conference on the illegal wildlife trade in 2018 when Gove was environment secretary. “I was asked to see William because he wanted to do everything he could to support the summit,” Gove said.

Later, when William was launching his homelessness project, Homewards, in 2023, Gove, as secretary of state for levelling up, housing and communities, was one of the politicians he went to see beforehand. “He had a pretty detailed knowledge of the challenges … I was impressed,” Gove said.

Over the five years between those two conversations — one as Duke of Cambridge, the other as Prince of Wales — there had been a change in William’s approach. “When I met him for the illegal wildlife trade, he was charming and quite self-possessed,” Gove said. “But it was more by way of, ‘What can I do to help?’ Here now as Prince of Wales it was more, ‘These are my plans.’ And while at certain points he deferred to members of his team, it was clear that he was chairman of the board. You could sense he had grown in authority and confidence.” But William, as would emerge later, is also capable of testing the constitutional boundaries.

A few days after October 7, 2023, the Prince and Princess of Wales joined the King in condemning the “barbaric acts of terrorism” committed by Hamas in its attack on Israel. The Waleses also expressed sympathy for the plight of Palestinians as well as Israelis “stalked by grief, fear and anger”. That William had concern for Palestinians should come as no surprise; his visit five years earlier to Israel and the occupied Palestinian territories had had a profound effect, and since then he had gone out of his way to keep himself informed of what was going on in the region. His 2018 visit — the first by a senior member of the royal family — had been William’s most significant overseas engagement to date, and one that had caused some nervousness on the part of both the palace and the government.

William’s foreign affairs adviser, Sir David Manning, was determined to make sure that William’s visit went smoothly. “We had to be sure that he would have access to the Palestinians, and be allowed on to the West Bank. It was very important to ensure that was understood in [Israel prime minister Benjamin] Netanyahu’s office.” He did not, he said, have to fight for that, but he was “plainspoken” about it.

Even when they agreed, Manning had to think: “Do we trust both sides? This is a minefield. You could not be certain what either side might do.” In the event, the visit was an enormous success. “They were impeccable. They all behaved exactly as they said they would.” Afterwards William became very interested in the Israel–Palestine problem. “He wanted when we got back to find out how it would be possible to stay engaged with both the Jewish community in Britain, and Palestinians,” Manning said. “Could the Royal Foundation in any way help philanthropically on both sides of the line?”

Avoiding trouble in 2018 was one thing; steering clear of controversy after October 7, 2023 was another. In February 2024 William released a statement about Gaza. Given the amount of comment that it provoked, it is worth quoting in full.

“I remain deeply concerned about the terrible human cost of the conflict in the Middle East since the Hamas terrorist attack on October 7. Too many have been killed. I, like so many others, want to see an end to the fighting as soon as possible. There is a desperate need for increased humanitarian aid to Gaza. It’s critical that aid gets in and the hostages are released. Sometimes it is only when faced with the sheer scale of human suffering that the importance of permanent peace is brought home. Even in the darkest hour, we must not succumb to the counsel of despair. I continue to cling to the hope that a brighter future can be found and I refuse to give up on that.”

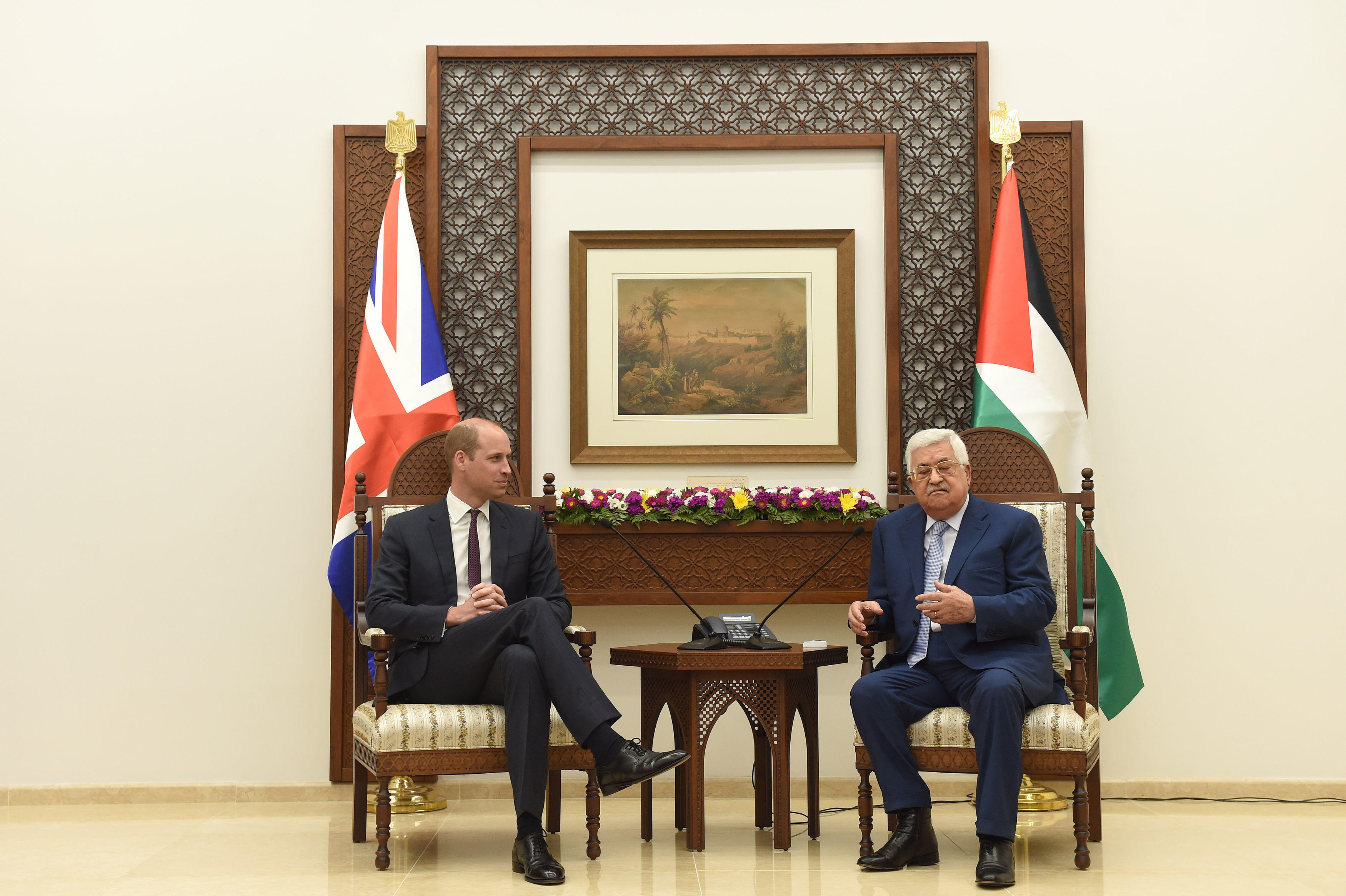

Prince William meets Palestinian Authority president Mahmoud Abbas in Ramallah, 2018

ALAMY

Suddenly, everyone had an opinion. William was making a “bold foray” into a complex area (The Guardian) or alternatively was making an “ill-timed and ill-judged” intervention (the Tory peer Stewart Jackson). “We were briefed it was happening,” a Foreign Office source told the royal biographer Robert Hardman, “but we were certainly not asked in advance.”

That is not entirely true. One can be sure that it went through the appropriate Foreign Office channels because it was actually written with the help of someone from the Foreign Office: David Hunt, who was on secondment to Kensington Palace to advise on foreign affairs. A draft was written, which was shared with the Foreign Office before it was released. A senior Whitehall source said: “The whole thing was worked through. The language was agreed between the palace and the Foreign Office before it went out.”

Yet David Cameron, then foreign secretary, did not actually know about William’s statement in advance, even though it had been shared with the Foreign Office. “There was a communication cock-up,” an insider said. Cameron’s office was only told about the statement hours before it was released and did not have time to brief the foreign secretary. “It had gone to the wrong person and sat on a desk, and we weren’t told.”

Manning was no longer working for William when he made his Gaza statement, but said that he believed it reflected what William felt. And the more senior royals become, he said, the harder it is for them to speak their mind. “Once you become as close to the throne as William now is, the pressures mount. You have to weigh every word three times instead of twice. You have got more pressure from the government, which is going to be worried about what you are up to. People are no longer going to say, ‘Well, he is a young man, he’ll learn.’ My guess is that he insisted. After all, he is the member of the royal family who has seen this on the ground. I think he was rightly very concerned about what was going on.”

There are questions about how exactly William will see his role as a constitutional monarch. His first private secretary, Jamie Lowther-Pinkerton, spoke to him at length about the essential principles of constitutional monarchy, especially the sovereign’s right to be consulted, to encourage and to warn. Lowther-Pinkerton also organised sessions for William with experts including lawyers and historians. He also had a number of long conversations over the years with Christopher Geidt when he was private secretary to the late Queen. Given that Geidt is a strong proponent of the principle that the sovereign should remain above politics, it is safe to assume that he placed great emphasis on it with William.

There was, however, one occasion on which the interactions between sovereign and government left William greatly disturbed. That was when Johnson wanted to prorogue Parliament at the end of August 2019.

William was furious. A 2021 profile of the prince by Roya Nikkhah of The Sunday Times suggested that things would be different when William was on the throne. He had, the article said, told friends that when he was King there would be “more private, robust challenging of advice”.

If that is really the case, there might be trouble ahead. Constitutionally speaking, advice is there to be followed, not challenged. When King Charles was told he would not be going to the Cop27 climate conference in 2022, he accepted the advice without question, even though it did not fit in with his plans. If William had indeed told friends that he was prepared to robustly challenge advice, was this a strategy that he had discussed with his private secretary? Was it something he had properly thought through? At least one senior Whitehall figure was privately dismissive of William’s suggestion that advice given to the monarch could be challenged. “It’s one of those things where if anybody thought about it for about 30 seconds, you’d realise that it’s a really stupid thing to say.”

Power and the Palace by Valentine Low (Headline Publishing Group £25). To order a copy go to timesbookshop.co.uk. Free UK standard P&P on orders over £25. Special discount available for Times+ members.