Normal text sizeLarger text sizeVery large text size

He was born into a storied Australian family famed for its entrepreneurialism – and for fierce intrafamilial fighting.

A legal feud over the multimillion-dollar estate of a member of the Hordern retailing dynasty is playing out in the Supreme Court in Sydney, decades after the last of the family’s shops were shuttered in NSW.

The case is one of a rising number of disputes over inheritances, and it highlights some of the common threads in wills and estates litigation.

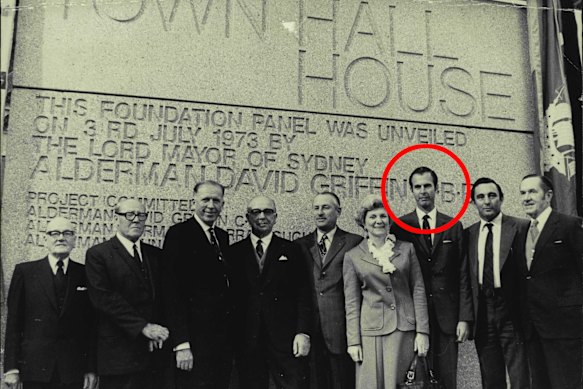

Hordern, shown here at the laying of the foundation stone for Town Hall House, served on the City of Sydney council from 1969 to 1974.Credit: Fairfax Media

Samuel Carr Hordern, a former stockbroker and City of Sydney alderman – a councillor, in the modern parlance – died in 2023, aged 94.

Under a will dated June 2017, he left the bulk of his estate, worth at least $10 million, to his second wife. He left his four children, including two stepchildren, $250,000 each.

His daughter Dinah launched proceedings last year against her stepmother in a bid to secure a greater share of the estate.

“Dinah informed me that she seeks an order for provision from the estate for approximately $7 million,” Justice Francois Kunc said in a preliminary decision in May.

Those proceedings are at an early stage, and orders made by the court last month suggest Dinah may re-work her claim and launch fresh proceedings to challenge the validity of the will. Meanwhile, Hordern’s son Matthew has launched a separate case.

Latest in Hordern family disputes

The cases are the latest in a series of Hordern disputes. Historically, separate family businesses competed against each other in Sydney.

Samuel Carr Hordern’s great-great-grandparents, English migrants Anthony and Ann Hordern, arrived in Sydney in the 1820s. Ann’s drapery business in Pitt and later King Street was the beginning of the retail empire.

The former Anthony Hordern and Sons building on the site of what is now World Square. This was run by a separate arm of the Hordern dynasty to Samuel Carr Hordern’s side of the family.Credit: Alan Gilbert Purcell/Fairfax Media

Their son Anthony II laid the groundwork for what became the sprawling Sydney department store Anthony Hordern & Sons, occupying the site of what is now World Square.

For decades this was a separate business to Hordern Brothers in Pitt Street, around what is now the MidCity shopping centre. Hordern Brothers was run by Samuel Carr Hordern’s side of the family.

Cutting the inheritance pie

Dinah Hordern’s claim started as an application for a family provision order. This is a way for those closest to a deceased, including current or former dependants, to seek a larger slice of the inheritance pie if inadequate provision was made for them in a will.

The number of family provision cases filed in the NSW Supreme Court has increased over the past 20 years, from 655 in 2005 to 996 last year.

But the claims are not a modern phenomenon.

“[It] had its origins in the Roman Empire,” said HWL Ebsworth partner Guy Moloney, an expert in wills and estates litigation. “They had laws like this in Rome, and then they were revived, first in New Zealand … in the late 19th century, and then Victoria, and soon every state and territory in Australia [followed].”

Moloney said the policy objective was to ensure that if a deceased estate had resources to support a person in need who had a moral claim to a share of it, provision was made for them to “ease the burden” on state resources. It was “social legislation” focused on need, not fairness, he said.

“The fact that it can override a person’s will is what creates consternation,” Moloney said. But he believed the laws generally achieved their objective.

Speaking hypothetically, Moloney said an estranged child who had been troublesome to a parent and had been cut out of their will might, “perversely, be the person who is in the greatest need” when their parent died.

He said part of his job was to advise clients drafting a will that “if you give this problem child nothing, that might incite a claim” for a family provision order. “The wise advice … might be to leave them something, if they can, [as] a deterrent amount,” Moloney said.

Turnbull Hill Lawyers partner Adrian Corbould, a specialist in wills and estates law, said family provision claims were “not a free-for-all”.

The categories of people who are eligible to seek a family provision order are relatively confined, such as a current or former spouse, de facto partners and children. The court must be satisfied adequate provision hasn’t been made for them on a needs basis.

Grandchildren or others who lived with the deceased may be eligible if they can demonstrate they were “wholly or partly dependent” on them at some point.

A person who is neither a spouse nor partner but is living with the deceased in a close personal relationship, sharing a household and providing care, is also eligible. But eligibility is just the first hurdle before an order can be made.

Corbould said the categories of eligible people reflected the “innate public feeling that you should, where circumstances warrant and permit, provide for your spouse and children [and other dependants] on your death”.

Lovers of a married deceased may emerge to seek a share. In a current case, a former football boss who lived what a NSW judge described as a “colourful but ‘hard living’ life” made a will shortly before his death leaving his entire million-dollar estate to his wife of 28 years. His lover in Greece wants the court to make an order giving her a slice of the estate.

The experts made clear the cases were about need. A financially secure person would have difficulty persuading a court they needed a family provision order.

“You have to prove ‘why do I need it’, not ‘why do I want it’,” Corbould said. “They’re the kinds of claims that settle for low tens of thousands, just to make them go away.”

Corbould noted the vast majority of wills were not contested, meaning a person was free to divide their assets as they wished and there was a “very, very good chance” it would not be challenged.

Rise in cases

While some of the increase in family provision claims may be attributable to population increases, Moloney and Corbould believe there are other factors at play.

Moloney said the generational wealth gap was growing, and it was getting “harder and harder for young people to do things like enter the housing market”.

Corbould believed the variety of cases would only become more “weird and wonderful” as multiple relationships, including second or third marriages, became more common.

“Life is just getting so financially hard,” Corbould said. “Earnings have not changed much.” Estates were also worth more as the value of even humble family homes increased markedly.

No will? There’s a way

Amid the tussles over wills, it is easy to forget it is not compulsory to make a will. “You do not have to make a will,” Corbould said. “The government has laws in place to divide your assets.”

Under the “imaginary will” imposed by those laws, the deceased’s entire estate would go to their current spouse if they had no children, or if they only had children with that spouse.

If the deceased had children from other relationships, their spouse would receive a basic share called a statutory entitlement – now more than $590,000 in NSW, but the figure is adjusted for inflation – and any remainder would be divided between the spouse and the children. Other relatives were in line if there was no spouse or children.

Tales of love and grief

Every will tells a story, often about love, but also about grief and pain. These are some of the cases before the NSW Supreme Court this year.

- Administration of one estate was “riven by bitter conflict for 33 years”, a judge said. At one point, two siblings took out AVOs against each other.

- One will included a clause directing that $2000 a month be given to the guardian of the deceased’s much-loved dog. Ultimately, the dog died before his doting owner.

- Another will directed that a woman be cremated with her teddy bear.

- A man died without a will. DNA testing confirmed he had fathered a child before his death. The court ordered that the child’s name appear on his headstone instead of “adored cousin and friend”.

Family provision claims can still be made where there is no will.

Moloney cautioned against leaving no will because it “risks an outcome you don’t want”. It was likely to lead to delays and costs, including in determining who should be the administrator. “A key thing a will does is appoint an executor,” he said.

Costs concerns

A major concern for parties in inheritance disputes is legal costs. In 2008, the then NSW attorney-general John Hatzistergos said there were “numerous instances of cost blowouts in family provision proceedings”.

One tool at the NSW Supreme Court’s disposal to rein in costs is its power to cap the legal costs recoverable by one party from another in the litigation, as well as the legal costs an executor can recover from the estate.

A costs-capping order may be made in family provision cases where the net distributable value of the estate is less than $1 million, but it can be made in any case.

Mediation is compulsory at an early stage, and most cases settle before court. Costs must be disclosed at this point.

“When they go beyond mediation, that’s when things get sticky and uncertain,” Corbould said. “That’s when the costs really ramp up.” He said the aim was to resolve the matter long before court.

Loading

Moloney said his “prime job” as a lawyer was to “fulfil almost a societal role of acting as a filter between the courts” and the parties to ensure “public resources weren’t wasted”.

“I always think that … if everybody does their jobs, you should be able to figure out a way to settle it,” Moloney said.

But sometimes the parties could not agree, and emotions ran high in this area.

“There is a very, very large bit of the Supreme Court of NSW’s business which is concerned with, in effect, reorganising the affairs of dead people, so that people in need can have that need satisfied,” Moloney said.

Start the day with a summary of the day’s most important and interesting stories, analysis and insights. Sign up for our Morning Edition newsletter.