“Winter, and I walked the sidewalk at night along banks of hard snow.”

From the first line of the first story, Night of the Living Rez immerses you in its world. Something unnamed creeps from the edges of every moment. The murky spectre of colonialism and dispossession haunts this collection. The ways in which an imposed society, an occupying force, continues to traumatise are explored through suspense and sparing magic realism. Each story is set against the backdrop of constant invasion. Unreality and surrealism are often the only ways to explore the unspeakable, the unexplainable.

‘In A Jar’ is particularly striking, beautifully told in a child’s voice. The logic, assumptions, and confusions of childhood frame the unnerving narrative perfectly. Domestic anxiety and structural oppression, not fully grasped by a child, is translated into a dangerous curse. The story captures how immediate the fear and humanity of children are. A smudging ceremony, his parents’ divorce, death, life, all described with the delicacy of a child beginning to understand. Between the tales of curses and hauntings, this story makes anything feel possible, and uses this to its advantage — otherwise ordinary lines now create a tightness in your chest, causing you to spiral into possibilities.

Unusual for a short story collection, the stories are directly connected: characters recur but never successively, reminiscent of those family members and friends you see only when you can make the time. The collection is punctuated with tradition, exploring just how much time and space is needed from everyday life to properly engage with Native American practices.

The connected vignettes create threads between past and present, self and community, love and conflict. We welcome Fellis as an old, unpredictable friend, and Frick as the mercurial father figure. The stories work on memory in a way I’d only experienced previously with very long novels, where you spend so much of your life reading it that the characters and plot become memories, begin to feel old and part of your personal history. The alternating recurrences produce a similar effect, and halfway through the collection the stories begin somewhere deeply familiar.

In a poignant moment, the protagonist of ‘Burn’ states he is not allowed to participate in a sweat lodge ceremony because he is in methadone treatment. In a few sparse lines, Talty calls to mind the extensive history of addiction being pushed onto Indigenous groups, and the ways in which the ills of postcolonial states bar Indigenous communities from engaging with their religion and tradition — the ways in which Western hegemony continues the cultural genocide of Indigenous people.

The final story, ‘The Name Means Thunder’, follows the last tragedies of the small family we have come to know. The adult narrator tells us he is no longer blind, but there was a time when he was. He takes us back to when he was a child, that voice so familiar to us at this point. Our young protagonist loses his vision when his sister’s baby dies. He only gets it back when they bury the body, when they perform the ceremony for the dead. He knows he can’t explain this to his doctor, and doesn’t try.

This final story contains, crystallises, all the swirling themes and reminders of Night of the Living Rez. The incompatibility of the two worlds that must both be inhabited, the negotiations of one’s identity and understanding, the loss of children, the encroaching of the state and outsiders, grief, empathy, community. This collection is humorously, heartbreakingly written, and its stories possess a magical quality that calls out to the reader. We are called on to examine the past, interrogate the present, and imagine the future.

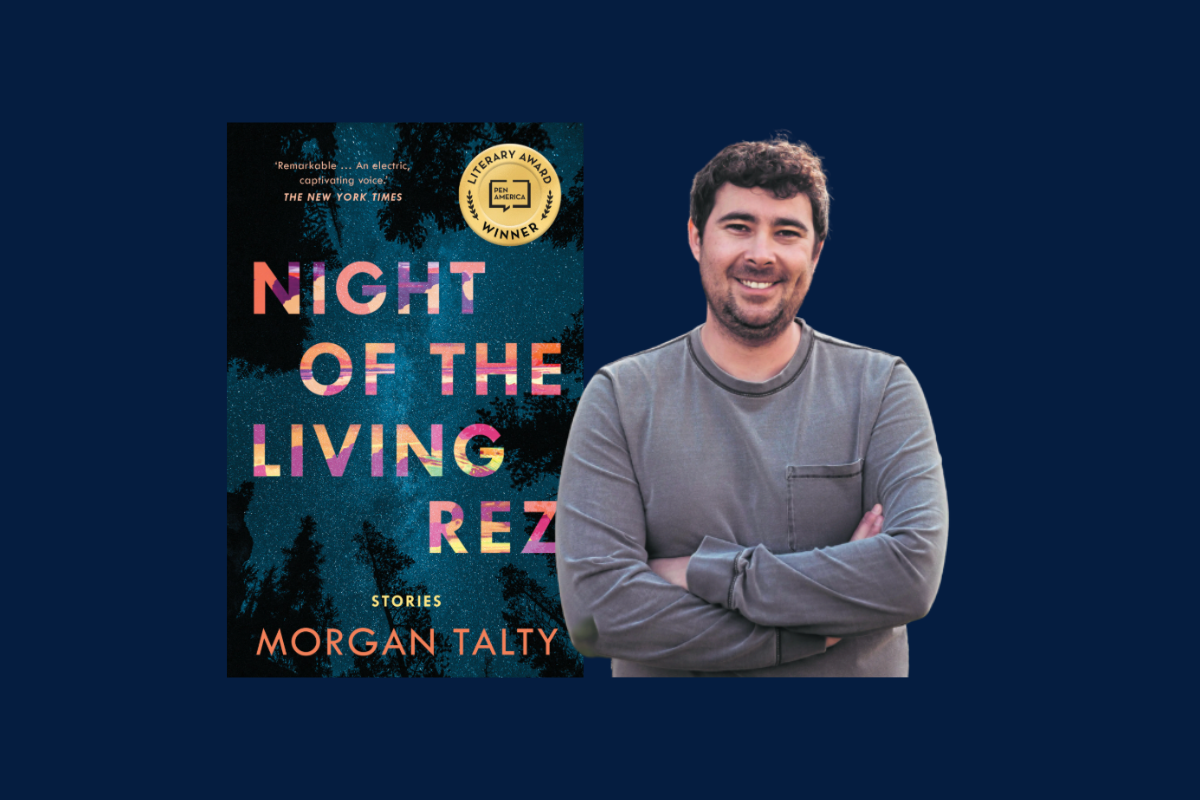

Night of the Living Rez was published on 2nd September by Scribe.