I am one of the lucky people standing outside Homeless Project Scotland’s night shelter with a home to go to. What is a few hours for me, is life for these men and women.

Colin McInnes, chairman and founder of the shelter, greets me. He tells me there are sometimes mothers and their newborn babies queuing up for a place to stay – but thankfully there are none here tonight.

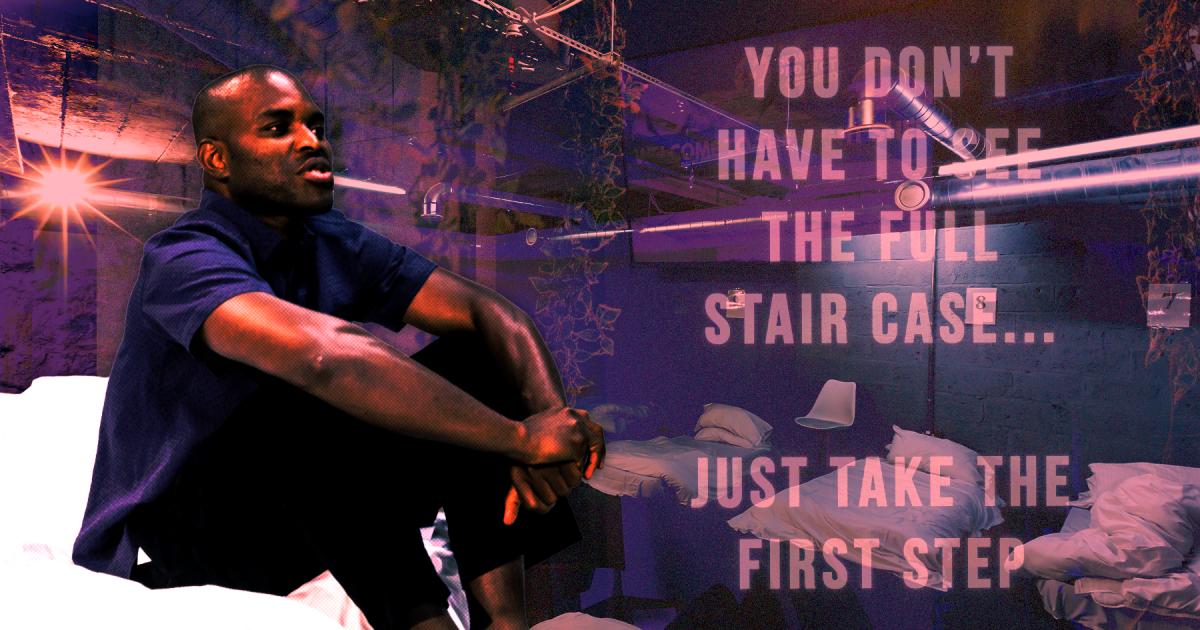

Colin McInnes, founder of the Homeless Project Scotland. (Image: Robert Perry) I am taken inside and follow Mr McInnes downstairs to an industrial unit that has been transformed into emergency accommodation.

I am one of the only journalists the charity has ever given exclusive access to since it opened in November 2023, and I could never have prepared for the stories I heard.

Immediately, I am shocked by the rows of chairs with bin bags hanging over them. The people who come here fill in their details, take off their shoes and empty any belongings they have into the black sack.

Read more:

They then wait to be processed, one at a time, walking through the security scanner and then being searched for weapons or drugs.

“I’ve had 27,000 people since November 2023 through this shelter and I have had nobody stabbed, nobody overdosed on drugs, nobody medically cardiac arrest, no fighting or battering each other, nothing.”

And yet, there is a tragic story around this shelter. At the time of my visit, it is just a few days away before Glasgow City Council rules on whether to close this facility.

The decision has since been postponed for a month but the fear of volunteers and service users is palpable.

Glasgow City Council said neighbours had complained about the queue of people waiting to access the shelter.

From my own observations, it took the men, and one woman, 45 minutes at most to enter. After that, all service users were unable to leave until the morning, unless they accepted they could not re-enter.

(Image: Robert Perry) Glasgow is in the midst of a homelessness crisis. It regularly breaches the unsuitable accommodation order thousands of times each year.

And Homeless Project Scotland, along with other homelessness charities, account for 80% of caseload each week as the lack of housing results in lawsuits in Edinburgh’s Court of Session.

First through security is Rufus, a Nigerian-born man who has been in Glasgow since April, but previously spent a number of years in London.

He has no recourse to public funds and is stuck in limbo until the Home Office decides on his immigration status.

For the last three months, he has been sleeping inside one of the dull, grey rooms underground on Glassford Street. Tonight, he is in a room with approximately nine other men, each with an identical single mattress on the floor, a pillow and a duvet.

Users of the shelter are subjected to 15 or 30 minute routine checks.

Read more:

There is two other male rooms and a female and child room, all cramped with as many beds as possible.

For Rufus, his energy is infectious, despite any hardship he may be experiencing in his life. But there is a sadness to him, a fear of how he will be perceived, particularly as protests sweep the country.

He said that people will never understand that men like him are not living in luxury and are instead just trying to survive.

In the morning, he will have nowhere to go and will roam the streets, take refuge in libraries or cafes. But tonight, he tells me he is “home”.

Another man, known as Matthew, from India, comes into the room. He had been here on a student visa for four years and overstayed for the last two years, too frightened to go home.

ervice users Rufus, left and Matthew lie on their beds for the night. (Image: Robert Perry) He puts his head in his hands at the thought of the shelter closing. “Oh my god,” he cries. “Where will I go?”

Rufus then says: “I haven’t been able to sleep at night worrying about this.”

I meet Mohammed, a 34-year-old man who fled Yemen for Europe four years ago.

The Middle Eastern nation has been locked in civil war since 2014 – a crisis only exacerbated by the country’s involvement in the Israel and Gaza conflict.

He crossed the English Channel in seven hours on a small boat, with dozens of other men, in March this year. After being granted asylum, he has relocated to Glasgow, but has found himself homeless.

“I was really scared,” he tells me as he described knowing men who have died in their pursuit of crossing the channel.

Mohammed. (Image: Robert Perry) “But it’s the only way. We are all running from countries that have conflict. It’s the only chance we have to make a better future, for ourselves but also for the next generation, so we flee.

“The UK is the safest place at the moment. All over Europe, there are protests and escalating rules against immigrants.

“But we found our opportunity here and we just need to be accepted, not to be hated for no reason. At the end, we are all civilians, we are all seeking the same thing – to be safe.”

Mohammed has a wife and child back in Yemen, who do not know he is homeless, and he hopes they can join him in the UK one day.

“It’s an opportunity to live a normal life here. It’s really frustrating when I see people protest against us.

“It’s for the misbehaving of really individual cases. We all know what some men do – but it’s not all of us. Good people cross the sea to be here, to be active in the community, to live our lives, to work and study and do normal activities.

Jallah, from Iran. (Image: Robert Perry) “People can’t understand why we take such a risk, but I’m watching the people protest against us and it is still safer here than being in my country. It’s sad.”

The qualified architect moved to Glasgow from Derby two months ago as he believes this is the city where you can make it.

“It’s not wrong to be a dreamer,” he adds. “I had to leave everything behind but it doesn’t mean that I give up and I’m not going to try again. I will keep fighting for myself and for my family.”

“I haven’t seen my family for four years – my wife and my child and my whole family.”

Read more:

It’s around 1am and I receive a tap on the shoulder after I have finished my chat with Mohammed. It is from Jallah, a Kurdish man from Iran who has asked another man in the shelter to translate for him.

This encounter is why I may never forget my night at Glasgow’s homeless shelter.

Through the translator, I am told Jallah came into the country 20 days ago following ongoing political unrest.

There has been conflict between the Kurdish ethnic group and the Iranian government, dating back centuries.

“The government executed his cousin yesterday,” I am told.

“He is in a bad situation, and he wants to try to be an asylum seeker here, he has no place to stay and he is in a bad way.”

By looking into Jallah’s eyes, it is clear to see he is a broken man. By this point, he is pleading with me, and the volunteers who have joined me, for help.

I will never understand the conditions in his home country that have made him so terrified, but his pain radiates from his body, and I believe him.

Before I leave, I catch up again with Mr McInnes. His anger at the lack of housing for those seeking refuge in Glasgow could not be more obvious and he is terrified about the consequences of the shelter being forced to close its doors.

“We’ve had mothers turning up with their children who have waited for hours on child protection social workers dealing with their situation. We’ve had a three-day old baby that came here on Christmas day in a Moses basket the first year we opened.

“This place has saved from the cradle to the grave. Not one council officer in Glasgow has come in here and saw our service. Not one person. And yet it could all be closed.”