Tweet

Email

Link

Birmingham, England

—

In his three decades in and around politics, Nigel Farage has been like a barometer – gauging Britain’s political climate to pick up on pressure points in the electorate. Now, he is more like the weather itself.

Although his upstart Reform UK party won just four parliamentary seats in last year’s general election, Farage, the maverick architect of Brexit, has since set the terms of Britain’s political debate, hounding the Labour government over its struggles to control illegal immigration.

Since the election, Reform has tried to refashion itself from a protest vote party to one that could govern – untried and inexperienced, but ready to step in if the Labour Party buckles under its own blunders, and the once-mighty Conservatives drift further into political irrelevance.

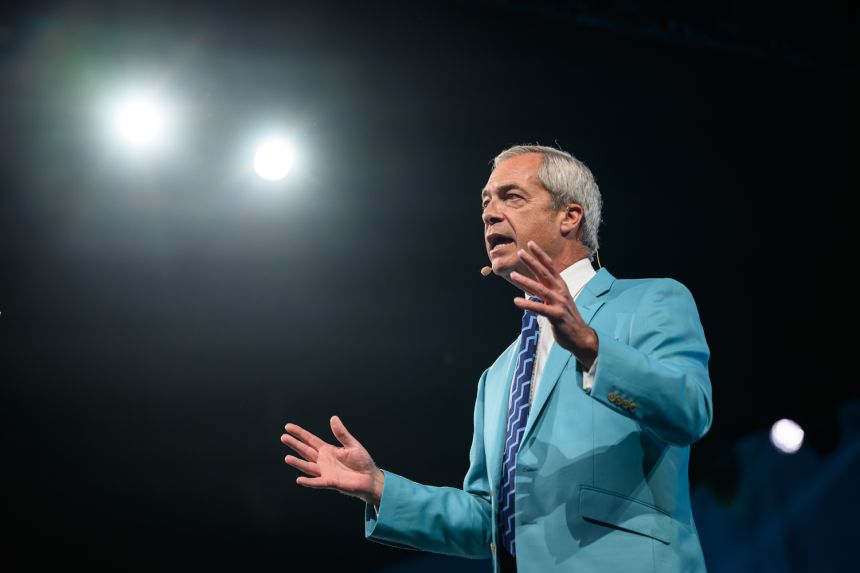

Reform’s ambition was on full display at its annual party conference in the city of Birmingham this weekend. Hours before Farage, the party’s leader, was set to give his keynote address Friday, news broke of more woes for Prime Minister Keir Starmer: His deputy, Angela Rayner, resigned following a scandal over her failure to pay enough property tax.

Keen to bolster Farage’s image as prime minister-in-waiting, Reform’s chairman, David Bull, shunted Farage’s speech forward by three hours, since “at a time of national crisis… we should hear from our leader.”

Farage told his rapturous audience that, despite Labour’s promise that it would bring “a new, different kind of politics, this is as bad, if not worse, than the one before.”

The next election is not due until 2029, but Farage – sounding buoyed by his recent weather-making powers – said “there is every chance of a general election happening in 2027, and we must be ready for that moment.”

Insurgent parties have historically struggled to break Britain’s duopoly held by Labour and the Conservatives. But this time could be different, said Luke Tryl, director of the polling firm More in Common, as Farage’s folky appeal meets an electorate increasingly willing to “roll the dice.”

“The range of possible outcomes is bigger than it has been at previous points in history,” Tryl told CNN. “The volatility of the electorate means that if, after the next election, Farage was prime minister, I would not be surprised.”

British political conferences are usually stolid affairs, but in Birmingham Reform was in party mode. As the members piled in – couples in Union Jack shirts, young people wearing “Farage 10” soccer jerseys – pints of beer were served promptly at 10 a.m. Friday.

Standing proud in his “Make Britain Great Again” hat, Danny Leggett, 17, is not old enough to drink alcohol, but said Farage appeals to him because he’s “happy to have a pint.” He’s someone with charisma, unlike the “robotic” Starmer.

Leggett isn’t sure when Britain stopped being great, but thinks it happened after World War II. Many on the British right have become convinced that victory in the war was in some way phony. Britain’s global standing declined afterwards, whereas Germany eventually regained its economic power.

In Farage’s telling, the United Kingdom’s decision to leave the European Union, a fringe pipe dream he helped make flesh, is another such victory – a revolution betrayed.

“We left the European Union, but they didn’t deliver Brexit, did they?” he said in his speech.

Jackie Dudley, one of 900 Reform councilors elected in May’s local elections, said she had abandoned the Conservatives because they’d failed to deliver a “real” Brexit.

“We didn’t get Brexit! If we did, we wouldn’t have the problem now with the ECHR,” she told CNN, referring to the European Convention on Human Rights.

Britain left the EU but remains a member of the ECHR – Farage’s newest scapegoat. Farage has vowed to leave the ECHR if elected, which he says would allow the UK to deport migrants deemed to be in the country illegally. Critics say leaving the convention, which is part of UK law, would have wide repercussions.

Throughout the conference, “detain and deport” – a Trump-style slogan – was used as a refrain among the speakers, to huge cheers.

Before last year’s general election, Farage said the results were a foregone conclusion and that the true fight would be the next vote. He proclaimed Reform as the UK’s “real opposition.”

Starmer could have rebutted this, pointing to the Conservatives’ vastly more numerous 121 seats. But this spring, he said Farage is the “real opposition,” elevating Reform from outsider status to Labour’s main rival.

Since then, Labour has appeared to dance to Reform’s tune. Starmer has taken a tougher stance on immigration, posting on social media about measures he is taking to deter illegal arrivals.

In attempting to attract Reform voters, Labour risks alienating its own progressive base, Anand Menon, a professor of European politics at King’s College London, told CNN.

“Immigration now being the top concern of the British voter is not a good thing for Labour. It’s only a good thing for Nigel Farage,” he said.

“It looks a bit like the tail is wagging the dog,” he warned. “It looks a bit like Labour doesn’t have any principles.”

For some voters, this helps reinforce Farage’s central appeal: his authenticity. “He says it like it is,” said one Reform member at the conference. “He’s a real bloke,” said another.

With only a small bridgehead in Westminster, Reform has just a few higher-profile politicians to roll out. There’s Lee Anderson, a burly former miner convinced Britain has “gone soft.” There’s the more polished Zia Yusuf, the party’s former chairman, now head of Reform’s Trump-style “Department of Government Efficiency.” And there’s Andrea Jenkyns, the mayor of Greater Lincolnshire, who arrived on stage singing a song she wrote herself, “Insomnia.” (Labour has been giving her “sleepless nights,” she explained.)

But the conference still feels like a one-man band. Everyone is here for “Nigel,” one of those rare politicians the British public feel they know on a first-name basis.

While everything seems to be going “Nigel’s” way, he is entering uncharted territory. It took Farage eight attempts – and 30 years – to win a seat in Westminster. His ability to accept his losses and return each time, wounds thoroughly licked, makes him what many Britons call a “good sport.”

But if Farage is a good loser, he is also a terrible winner. Since his Brexit dream came true, he has been miserable about it. His politics feed on grievance, on railing against “the establishment” – what happens if he becomes it?

Already, Farage has made bold promises he may struggle to keep. He pledged in his speech to “stop the boats” bringing asylum seekers to England’s shores “within two weeks of winning government.” Economists warn his low-tax, high-spend program would spook the bond markets.

But for the Reform members, those fears are for another day. At last, they feel Britain has a politician with a bit of agency. While the more technocratic Starmer risks presiding over a “computer says no” government, said Tryl, the pollster, Reform “is the party of can – we can control our borders, we can tackle crime, we can cut your taxes and get rid of (government) waste.”

There was a stark end-of-days feel to the conference. The members seemed united in two beliefs: Britain is broken, and only “Nigel” can fix it.

Once she finished singing, Jenkyns asked the exultant crowd to stand and chant in unison: “Nigel will be prime minister. Reform will save Britain.”

It’s a sentiment Farage is only too happy to fan. Britain isn’t as doom-and-gloom as he says it is but, if he is to be its savior, his voters need to believe that.

“Our country is, without doubt, in the most dangerous place it’s been in my lifetime,” he said, gravely. “We are the last chance the country has got to get this country back on track.”

Farage may have been preaching to the converted but, as the membership filed out of the conference hall in Birmingham – all tweed and turquoise – it wasn’t hard to imagine they will be joined by new disciples elsewhere.