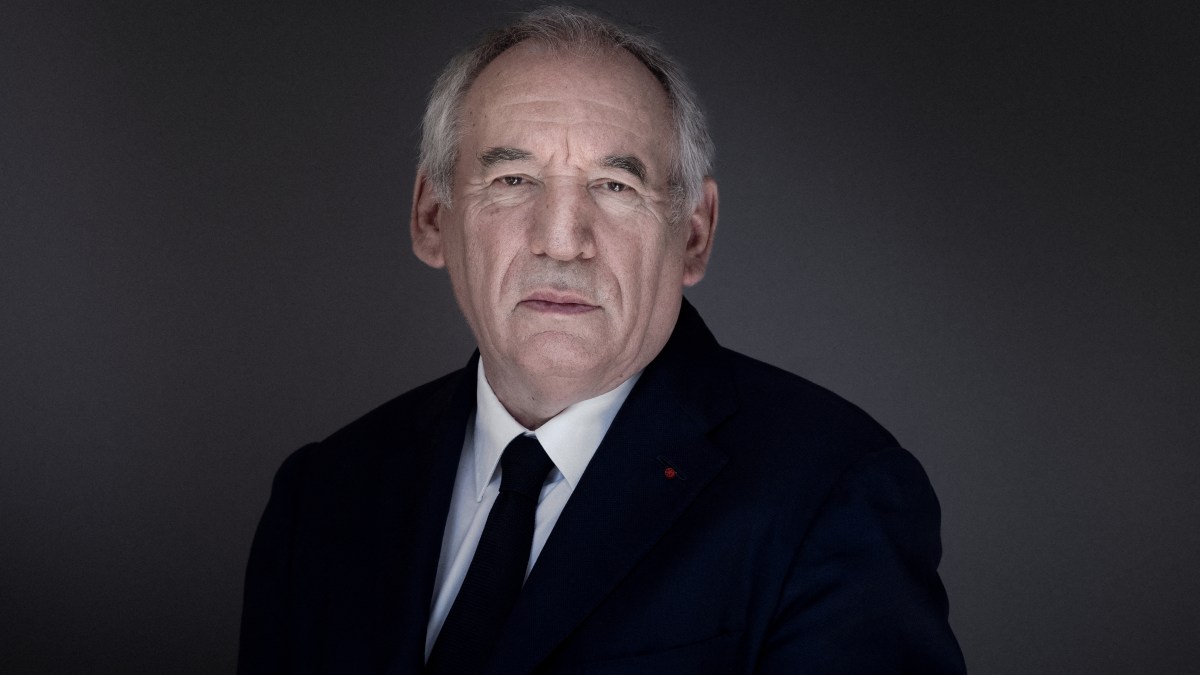

François Bayrou’s attempts to control the national debt were not popular

JOEL SAGET/AFP/GETTY IMAGES

When in 1958 Charles de Gaulle did away with the chaos of France’s immediate post-war Fourth Republic and replaced it with the Fifth, equipped with a powerful presidency and a subordinate legislature, the days of instability (21 administrations between 1946 and 1958) were meant to be over. No longer. French prime ministers have always been expendable, but the current rate of turnover suggests a country returning to its old volatility.

On Monday it was the turn of François Bayrou to join that sacrificial club, becoming the fourth ex-prime minister since mid-2022. His offence? To try to make a modest impression on a national debt totalling 114 per cent of GDP and a deficit of 5.4 per cent.

A centrist like his president, Emmanuel Macron, Mr Bayrou made his proposed budget, involving £38 billion of cuts, the subject of a vote of confidence in France’s national assembly. But like some tousled aristocrat trundling along in his tumbrel towards the Place de la Concorde, he could have harboured little doubt about the fate awaiting him. France is in denial about its crumbling finances. Propose cuts to spending and it’s you who will suffer the unkindest one of all.

• French government crisis deepens as prime minister loses confidence vote

Having ignited this instability by calling an unnecessary election that resulted in an assembly cut three ways between the left, centre and far right, President Macron is now searching around for another politician prepared to put his neck on the block in the cause of austerity. He himself has no intention of answering the call of Marine Le Pen, leader of the populist National Rally, to resign early from his second five-year term, due to end in 2027. More months of uncertainty, of stumbling, lash-up administrations, lie ahead. And while France’s politicians indulge in these theatrics the bond vigilantes circle, waiting to pounce.

“You have the power to overthrow the government but you don’t have to power to erase the truth,” Mr Bayrou scolded the assembly in his valedictory address. He was right. The casualties of this collision, in which the irresistible force of the French people’s sense of entitlement crashes into the immovable object of the national debt, will be France’s youth. After 51 years of borrowing the country was addicted to other people’s money, said Mr Bayrou. MPs heckled. In France, speaking the truth on the economy is considered declasse.

Not to be outdone by their legislators in the fantasy stakes, France’s wonderfully unreconstructed trade unions are set to hold a general strike tomorrow to protest against austerity. Its equally wonderful and nihilistic rallying cry? Bloquons tout! (Let’s block everything). In his eagerness to save France from itself Mr Bayrou went too far and suggested cutting two of the country’s 11 national public holidays (England has eight). You do not part a Frenchman from his free time and this foolhardy proposal, almost as toxic as raising the state pension age, did little for his otherwise rational cause.

• Jason Cowley: Here’s why people across Europe are rising up against the ruling classes

France is insulated from the bond market to a greater degree than Britain because of the shelter provided by the European central bank, which can buy up member states’ bonds. This has exercised a baleful effect on French fiscal discipline. With no immediate threat of a Trussian debt crisis there is no incentive for politicians to make hard choices about, for example, the country’s generous welfare regime. The ECB has allowed itself to become another fiscal lever for its more reckless participants. At some point, however, that £2.9 trillion immovable object will make its presence felt.