Before she drew a blank at Lahan Al Hayat, she had visited Syria’s Social Affairs Ministry.

There she was told the minister was abroad, the manager in charge of the missing persons file was on holiday, and then finally that work on missing children had been transferred to a security agency on the ministry’s fifth floor. Reem went upstairs, accompanied by a BBC film crew. We were promptly told to stop filming despite having permission to do so, and the ministry refused to provide Reem with any further assistance.

A new investigation into the fate of the children under the previous regime was announced by the ministry in May. But it has limited staff and resources, with just a few volunteers tasked with reviewing thousands of documents, and has yet to release any findings.

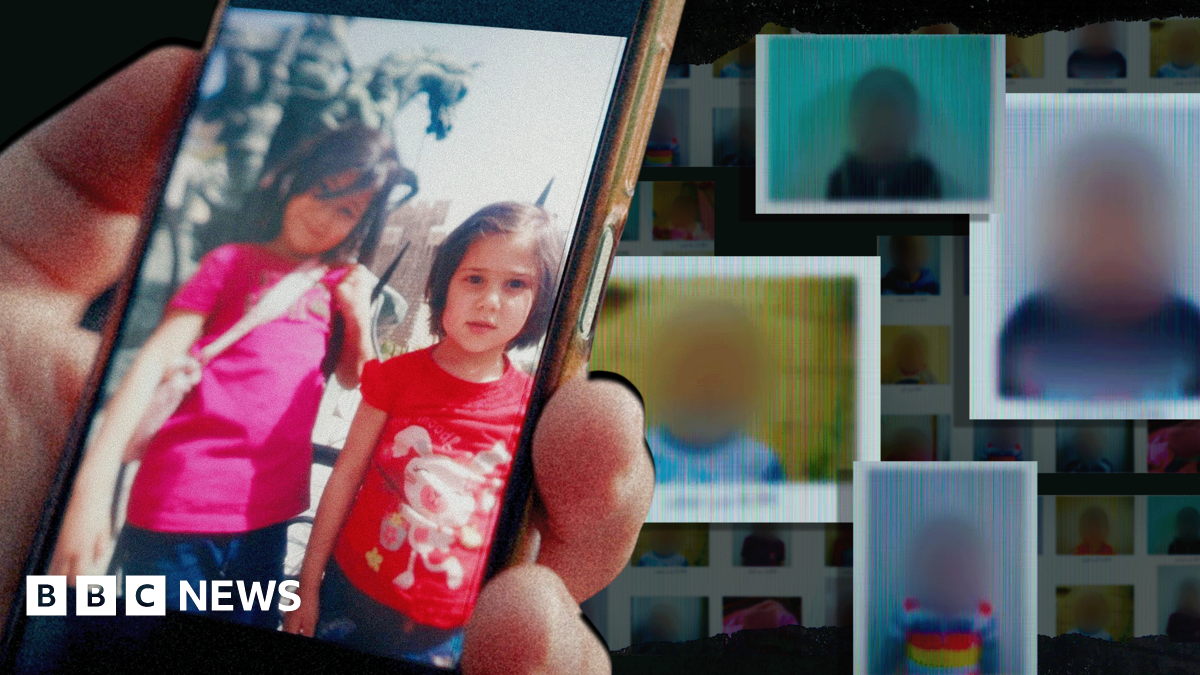

Reem next visited another orphanage known for taking in boys of Karim’s age. On her phone, she pulled up her son’s photo and showed it to the institution’s director. The woman responded with a silent shake of the head. Reem’s eyes filled with tears – a rare break in her steely composure.

Finally, she visited SOS Syria, which was led until recently by Samar Daaboul, the daughter of a close Assad aide. Ms Daaboul has denied her family links have influenced her work.

Reem was asked for Karim’s date of birth, but she pointed out to staff that this may not be of any use given records were often changed. Instead, she asked to see photos of the children SOS had taken in. It refused, citing the need to guard privacy.

A few weeks later, she received an email from SOS International to say the charity would respond to her within six months and recommending she also contact SOS Syria – the institution she had just visited – directly.

Other parents we have spoken to have told us they are still waiting for a response from SOS months after contacting it.

We asked Benoît Piot, the interim CEO of SOS Children’s Villages International, why paperwork from the Ministry of Social Affairs indicates children were being transferred to SOS up until 2022.

The team in Vienna was “not aware” of this, he said, adding that the external investigation it has launched into the children “forcibly placed with [SOS]… can get to the truth” and that SOS would note this finding and look into it.

We pointed out that SOS still operates in other human-rights abusing countries. Mr Piot stressed that the advice SOS International gives to its members is: “Don’t accept [children] if they have been separated for a bad reason.

“We are making sure that the admission of children in our programme is up to international standards,” he added.