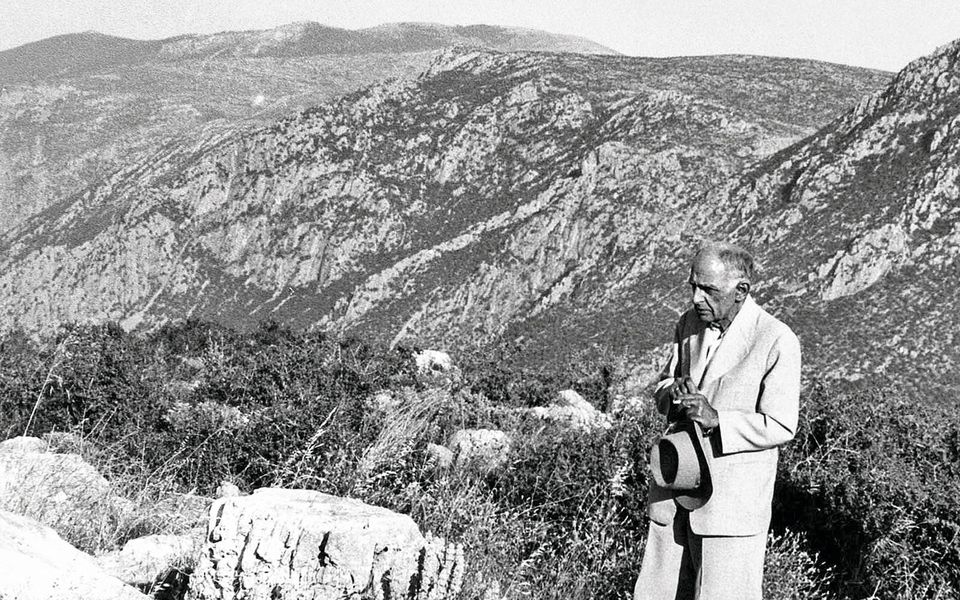

Architect and painter Dimitris Pikionis in Delphi, central Greece. [Benaki Museum/Modern Greek Architecture Archives]

“Above all, Dimitris Pikionis was a painter and a calm man. For him, art was the path to nature. His exhibition, presented in the 21st century, may help us recover the slow passage of time and remind us that architecture can be an act of reflection, culture and deep connection with the world,” Dr Covadonga Blasco, one of the two co-curators of the exhibition “Dimitris Pikionis: An Aesthetic Topography,” tells Kathimerini.

The exhibition, which was shown in Madrid between February 14 and April 27, aimed to demonstrate the creative process of the influential Greek architect through six of his architectural works, and was organized jointly by the Benaki Museum, the Cervantes Institute of Athens, the Italian Cultural Institute of Madrid, and the Greek Embassy in Spain. It was produced by the Circulo de Bellas Artes de Madrid.

This particular exhibition is now coming to Athens, opening at the Benaki Museum on October 22. So, while we wait to see in Greece the material that emerged from the thorough research of the Spanish architects and co-curators of “Aesthetic Topography,” Blasco and Juan Miguel Hernandez Leon, we wanted to find out why the architectural community of Madrid decided to honor Pikionis.

“Pikionis’ work is known to specialists, but remains almost unknown to the general Spanish public,” Blasco says. “It is usually mentioned only in relation to the shaping of the landscaping of the access to the Acropolis Hill. However, in a time of crisis of European foundations, we wanted to highlight the complexity of his personality, how he sought to reconcile Greek identity with artistic modernity. The exhibition delves into his life and work through six emblematic architectural works, which reveal his unique vision of the landscape as a work of art.”

View toward the Acropolis from Philopappou Hill. ‘Most visitors were impressed by the model constructed to show Pikionis’ intervention on the Acropolis, around which the entire exhibition discourse revolves,’ says curator and architect Covadonga Blasco. [Circulo de Bellas Artes]

View toward the Acropolis from Philopappou Hill. ‘Most visitors were impressed by the model constructed to show Pikionis’ intervention on the Acropolis, around which the entire exhibition discourse revolves,’ says curator and architect Covadonga Blasco. [Circulo de Bellas Artes]

Pupil of Parthenis

Pikionis was born in 1887 in Piraeus and in 1906 became the first pupil of the painter – then professor at the National Technical University of Athens – Konstantinos Parthenis. Two years later he received his civil engineering diploma and, being a student of such a teacher, he left to study painting in Munich, and then in Paris. There, he came into contact with modern movements, especially the work of Paul Cezanne and Paul Klee, and the sculpture of Auguste Rodin, while at the same time attending courses on architectural composition and working in architectural offices.

At the beginning of the 20th century, Pikionis had to face the pressure for residential development in his country. Reconstruction was not only a necessity but also a moral mission

Returning to Greece, he continued his work in architecture and painting and was a member of a select group that introduced the European avant-garde to Greece. Although he was a contemporary of architects such as Le Corbusier and Mies van der Rohe, his architecture sought to integrate tradition with modern abstraction.

“At the beginning of the 20th century, Pikionis had to face the pressure for residential development in his country. Reconstruction was not only a natural necessity but also a moral mission. In all his construction and renovation plans, we see that his architecture is placed at the service of Greek culture, with examples such as the Pefkakia primary school, on Lycabettus Hill, and the Xenia Hotel,” Blasco says. “Pikionis wanted to contribute to the reconstruction of his homeland, but not in a superficial, profitable way. He wanted to do so from his position as a Greek citizen. Similarly, in Spain in the 1950s a similar concern arose: to achieve the recovery of a modernity based on the Mediterranean tradition that represented the authentic Spanish identity. The Alhambra Manifesto and the work of architects such as [Fernando] Garcia Mercadal and Jose Luis Sert demonstrate this common cultural quest.”

The exhibition focuses on Pikionis’ topography of the entrances to the Acropolis Hill, filled with visual references to its pavements. The work was completed, after a long and complex construction process, in 1958. The architect’s images and drawings are interspersed with his own words, conveying his handwritten notes, thoughts and vision. As Hernandez Leon noted, “Pikionis sought to raise a question of identity in art, combining Hellenism with modernism.”

According to the Circulo de Bellas Artes, “Aesthetic Topography” was warmly received in Madrid and attracted international interest. More than 5,000 people visited it, while many Greeks passing through the city were surprised to discover an exhibition dedicated to “their” architect.

Characteristic elements of Pikionis’ slated route that leads to Philopappou Hill. [Circulo de Bellas Artes]

Characteristic elements of Pikionis’ slated route that leads to Philopappou Hill. [Circulo de Bellas Artes]

Intervention on the Acropolis

“Most visitors were impressed by the model constructed to show Pikionis’ intervention on the Acropolis, around which the entire exhibition discourse revolves,” says Blasco.

Indeed, in this exhibition, which is divided into the themes of painting and thought, architecture and model, moving from the personal element of the first part to the architectural achievements of the second, the visitor ends up in the third section where a three-dimensional depiction of the Acropolis and Philopappou Hill area dominates, in which Pikionis’ morphological intervention is seen in its entirety.

We ask Blasco which aspects of Pikionis’ approach to mixing tradition and modernism she believes are most relevant to contemporary architectural practice. “The best contemporary architecture takes into account its relationship to site and landscape. In fact, the recent concept of ‘urban landscape’ heritage responds to the understanding that architecture and building have a duty to engage in a dialogue with what already exists on site,” she explains.

“In his writings, Pikionis refers to the fundamental relationship between individual things (the parts) and the whole as ‘universal harmony.’ We argue that this relationship also exists in all quality architecture (whether modern or classical). Our goal with this exhibition was not only to highlight the magnificent legacy of Dimitris Pikionis in the 21st century, but also to recover a ‘sensitive gaze’ that leads us to understand him better today than in the past.”

A detail from the Church of Agios Dimitrios Loubardiaris on Philopappou. [Circulo de Bellas Artes]

A detail from the Church of Agios Dimitrios Loubardiaris on Philopappou. [Circulo de Bellas Artes]