Natural England has finally got around to publishing the data for the 2025 Hen Harrier breeding season, which demonstrate very clear differences between areas managed for conservation and those managed as privately-owned grouse moors.

The headline on Natural England’s blog (‘Numbers of nesting hen harriers in England have risen slightly in 2025‘) is technically accurate but I would argue it’s also cynically misleading because it only tells half the story, and the half that’s missing provides the all-important context required to understand the ongoing threats facing Hen Harriers in England (and some other parts of the UK) – that of the illegal killing of this species on moorland managed for driven grouse shooting.

I say this is cynical because the headline as it’s written is handy for (a) Natural England, (b) Defra and (c) the grouse shooting industry, who can (and will) point to it as an indication of a so-called ongoing ‘conservation success story’ when they’re being criticised by conservationists for not doing enough to tackle the relentless persecution of this species.

If you bother to delve deeper than the headline and drill down in to the figures, it’s crystal clear that Hen Harrier persecution is still so rampant on many driven grouse moors it’s suppressing the distribution of this species at a national level.

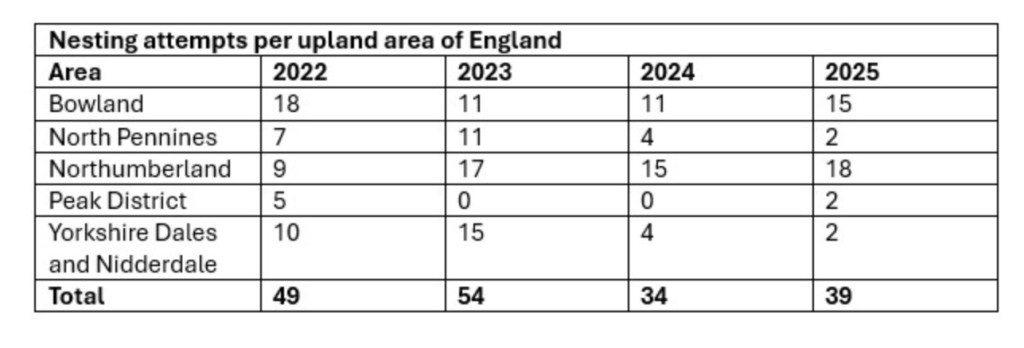

According to Natural England’s data, there were 39 nesting attempts in 2025, of which 33 were successful, up from 34 attempts (25 successful) in 2024. Natural England has presented the breeding attempts data in the following table:

The context to these data, which Natural England has failed to include, is the predominant land use in each of those areas. If you’re a casual reader with no understanding of those areas, you’ll think that Hen Harriers are doing ok in some areas and not so much in others, but you’ll have no clue about the differences in land management between those areas and therefore the influence of that land management on Hen Harrier nesting attempts.

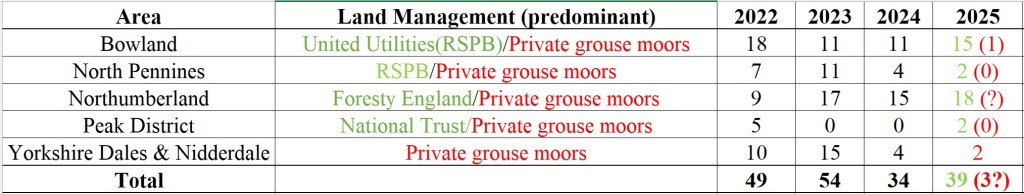

I’ve annotated Natural England’s table to show what’s actually going on:

You can now see the predominant land management in each area and it becomes apparent that the areas predominantly managed for conservation (in green) are the areas where most Hen Harrier nesting attempts took place, compared to the low number of nesting attempts on privately-owned grouse moors (red) where Hen Harriers are not welcome.

For example, in Bowland, Lancashire, there were 15 nesting attempts this year, and all of them except one were on moorland owned by United Utilities, wardened by the RSPB.

In the whole of the North Pennines, the only two nesting attempts were on the RSPB’s Geltsdale Reserve in Cumbria.

But even on these protected sites, Hen Harriers weren’t safe; four breeding males ‘disappeared’ during the breeding season, suspected to have been killed whilst hunting on nearby grouse moors, and nests were only successful thanks to the intervention of the RSPB.

In the Peak District, the only two nesting attempts were on moorland managed by the National Trust.

In the Yorkshire Dales and Nidderdale, the only two nesting attempts were on privately owned grouse moors, down from a high of 15 nesting attempts in 2023. Interestingly, raptor fieldworkers report that there weren’t any nesting attempts on Swinton Estate this year – the grouse shooting industry’s poster child for Defra’s ludicrous Hen Harrier brood meddling trial where the estate championed the removal of some Hen Harrier chicks which were reared in captivity before being released elsewhere. Word has it that the grouse shooting at Swinton has now been leased and that Natural England fieldworkers were not welcome this year. There are also unverified reports that the winter roost site on Swinton Estate ‘is no longer there’. More on that if I receive further information.

Hen Harrier nesting attempts in Northumberland this year are a little less clear. There were 18 known attempts, and the majority of those are likely to have been on Forestry England-managed land at Kielder, a known hotspot for Hen Harriers in recent years, although it’s possible that a couple of attempts may have been recorded on nearby privately-owned grouse moors.

So it looks like there were probably between 3-5 Hen Harrier nesting attempts on privately owned grouse moors in England in 2025; the rest of the 39 nesting attempts took place on land managed for conservation.

It would be helpful if Natural England would publish the associated land management information alongside the data on Hen Harrier nesting attempts, and the subsequent outcome of those attempts – it used to do this. Why has it stopped?

To be fair, beyond the headline and the table in Natural England’s blog, there are some clear statements acknowledging the ongoing issue of Hen Harrier persecution, although in my opinion they could still be much more explicit about the unequivocal link between HH persecution and driven grouse moors:

‘Hen harriers are rare primarily because they are killed and prevented from nesting successfully‘ [on many driven grouse moors];

and

‘This population recovery remains fragile, and efforts to reduce illegal killing and disturbance of hen harriers remain necessary across much many driven grouse moors of in the English uplands‘.

It’s also notable that Natural England did not mention any of this year’s suspected and confirmed Hen Harrier persecution crimes in its blog, and nor has it updated its database on the fates of its satellite-tracked Hen Harriers. The last update was in April 2025. Typically, NE has updated the database every 3-4 months – it’s now been six months. Natural England, along with various police forces and the National Wildlife Crime Unit’s Hen Harrier Taskforce, is still suppressing information about an estimated 20 incidents, some of them dating back over 18 months.

Why is that?