Biologists in Brazil have documented a jaguar swimming an estimated 2.3 kilometers, or 1.4 miles, across an artificial reservoir in the Cerrado savanna, the longest confirmed swim by the species to date. The previous scientific record, published in 1932, was of a jaguar swimming 200 m (660 ft).

“We knew that jaguars might have this ability to swim long distances. But what was missing was a confirmation through a technical record. That is the big difference here,” lead author Leandro Silveira, a biologist with the Jaguar Institute, told Mongabay by phone.

Researchers first encountered the male jaguar (Panthera onca) from a camera-trap image in May 2020 on the shore of the Serra da Mesa hydroelectric reservoir in Goiás state, central Brazil. Four years later, in August 2024, a camera on an island in the reservoir captured the same individual.

A thin outcrop is the only strip of land in the water separating the island from the mainland. This may have served as a halfway point, meaning the jaguar would have swum the first 1 km (0.6 mi) there, then completed the remaining 1.3 km (0.8 mi). The minimum distance considered is still more than six times the previous record.

For Silveira, the jaguar using the strip of land as a pitstop is technically possible and important to consider, but he said a direct swim is more likely.

“That idea of using the small islands to stop along the way and rest is a very human interpretation … He [the jaguar] doesn’t think like this,” Silveira said. “We can’t be incisive about these answers. We have the documentation, the irrefutable data that shows the event has taken place. But the rest is interpretation.”

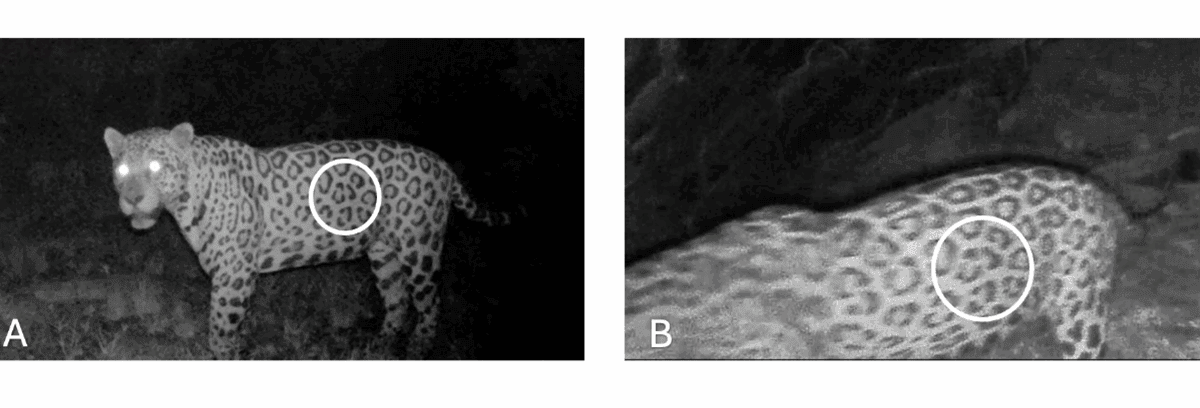

A jaguar was photographed by camera traps at locations 1 and 2 in the Serra da Mesa reservoir. Image courtesy of Silveira et al., 2025 (CC BY 4.0).

A jaguar was photographed by camera traps at locations 1 and 2 in the Serra da Mesa reservoir. Image courtesy of Silveira et al., 2025 (CC BY 4.0).

Silveira said the jaguar appeared healthy in the 2024 footage, showing no signs of exhaustion after the swim. “The biggest surprise is that this was a natural behavior. The jaguar was not fleeing from a flood or catastrophe. He simply swam across.”

Until now, accounts of jaguars swimming long distances had largely been circumstantial or anecdotal. On Maracá Island, at least 6 km (3.7 mi) off Brazil’s northeastern Atlantic coast, a jaguar population has remained genetically healthy. Silveira said this suggests occasional crossings, backed by reports from fishermen, even though no scientific record exists.

“Evidence like this is very rare,” Fernando Tortato, conservation scientist at wildcat nonprofit Panthera, who wasn’t involved in the study, told Mongabay by phone. “We now know that a crossing may be difficult, but possible, that [the body of water] doesn’t constitute an absolute barrier. With this you can better understand how jaguars might move through a landscape.”

Banner image: Camera trap images of the jaguar before and after the crossing. Image courtesy of Silveira et al., 2025 (CC BY 4.0).