Contents

Limitations of the Current Proposal 3

The Information Technology and Innovation Foundation (ITIF) is pleased to submit these comments in response to the European Commission’s call for evidence on the Commission’s proposed European Innovation Act (EIA).[1] ITIF is a nonprofit, nonpartisan public policy think tank, committed to articulating and advancing pro-productivity, pro-innovation, and pro-technology public policy agendas around the world to spur growth, prosperity, and progress.

The European Commission should take bold steps to reverse Europe’s declining competitiveness. As a forthcoming ITIF analysis of the OECD’s Trade in Value Added Data series will show, for 10 major advanced industries (e.g., computers and semiconductors), the EU’s share of global value added fell from 22 percent in 2000 to just 16 percent in 2022, and its location quotient (a measure of specialization relative to the rest of the world) has remained about average, falling from 3 percent above the relative global average to 2 percent above par. The EU 17 fell from 4 percent above average to 1 percent above average.[2] Moreover, from 2005 to 2024, Europe’s share of global economic output fell from roughly 33 percent to 23 percent, meaning that Europe’s share of the global economy is now likely the lowest it’s been since the Middle Ages.[3] Something is going wrong. Without a decisive course correction, Europe will continue to fall further behind the global pace.

The EIA aims to create an innovation-friendly environment that supports the growth of innovative companies in the EU. ITIF welcomes this initiative—it outlines how to address innovation constraints that are long overdue in Europe. However, the European Commission cannot rely solely on the EIA to close its competitiveness gap. While the EIA correctly identifies barriers such as a challenging regulatory environment, limited access to capital, and insufficient late-stage support for scaling projects, it focuses too narrowly on the startup ecosystem. By doing so, the EIA misses the structural competitiveness issues that undercut Europe’s innovation capacity.

For the EIA to succeed, the Commission needs to address Europe’s broader economic policy environment. The EU’s reliance on the precautionary principle has entrenched a risk-first mindset that slows innovation and diverts resources away from competition and quality improvement. For example, the overreliance on the precautionary principle will hinder Europe’s adoption and diffusion of artificial intelligence (AI), as it increases costs, lowers product quality, and reduces consumer options.[4]

Europe’s innovation capacity faces a geopolitical dimension that the Commission should both acknowledge and address. Europe’s weakening competitiveness increases its vulnerability to the West’s strategic rival, China. European champions now lag Chinese competitors in key sectors such as automobiles and telecommunications equipment, weakening Europe’s long-term economic security.[5]

To combat the stated problems above, ITIF recommends that the European Commission:

1. Use the innovation principle as the guideline for EU digital regulation.

2. Establish an Office of Innovation Review to serve as an “innovation advocate” within the EU.

3. Establish a “28th Regime.”

4. Increase the commercialization capacity of European universities.

5. Implement a “Bayh-Dole Act-like” framework governing university ownership of intellectual property (IP) derived from public research and development (R&D) funding.

6. Deepen pools of risk capital, in part by permitting pension funds to invest in venture capital.

7. Increase the continent’s R&D intensity to at least 3 percent.

The Commission’s assessment of the roots of the European innovation deficit is incomplete. The EIA correctly identifies regulatory burdens, lack of access to capital, and insufficient support for phases close to commercialization as innovation constraints for EU companies. Yet, these reforms do not tackle the core causes of the EU’s competitiveness lag. The EIA proposal does little to address its identified regulatory burdens head-on, preserving the EU’s traditional regulatory stance that impedes taking risks and the dispersed markets that constrain access to capital and a large market to scale.

The EIA fails to challenge the precautionary principle, which prioritizes hypothetical risks over tangible benefits, that underpins Europe’s regulatory framework by forming part of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union (TFEU).[6] Whilst the TFEU frames the precautionary principle within environmental policy, a communication by the EU on the principle clarified that, in practice, it applies far beyond this, to include all aspects of consumer policy.[7] As such, the precautionary principle guides many consumer protection laws, including the General Data Protection Regulation, Digital Markets Act, Digital Services Act, and Artificial Intelligence Act.[8] These laws raise compliance costs and delay time-to-market, diverting resources away from competition and quality improvement.

The EIA proposal insufficiently supports innovation across the regulatory pipeline, failing to acknowledge the Regulatory Scrutiny Board (RSB)’s latest reports on the EU’s Better Regulation initiative which serves to simplify regulatory burdens and facilitate compliance so that innovations can reach European markets quicker.

Without fundamental changes to address the EU’s growing innovation deficit, the EU will continue to fall into global irrelevance, and risk becoming a vassal state to its strategic competitors. Mario Draghi himself called for the use of economic statecraft to assert European freedom.[9] A coherent competitiveness strategy that leverages innovation to boost Europe’s strategic industries is therefore integral to the EU’s survival.

ITIF offers the following policy recommendations to boost Europe’s innovation capacity.

The European Commission should replace the precautionary principle with the innovation principle as the guideline for its digital regulations. The precautionary principle calls for regulations to pre-emptively mitigate potential risks, even when there is no evidence of harm. While this approach is intended to protect consumers, in practice, it often results in restrictive frameworks that slow innovation and increase compliance costs with little to no benefit. By contrast, the innovation principle—a policy to promote innovation for environmental, social, and economic objectives and harness future technological advances—offers an alternative approach that better balances risk mitigation with technological opportunity.[10] The innovation principle currently sits within the EU’s Better Regulation initiative, both of which require reform that the Commission should address in its EIA proposal.

The EU initially introduced the Better Regulation initiative to guide the development of regulation to reduce complexity and burdens.[11] The initiative aims to simplify and better implement regulation to enable European competitiveness, detailing guidelines and tools that the European Commission can use to achieve these aims. For example, the initiative includes a mandatory competitiveness check for every regulation proposed by the European Commission, and a voluntary consideration of the innovation principle, both intended to ensure regulation does not hamper European competitiveness and innovation. In practice, however, these tools fall short: assessments are often inconsistent, poor quality, and fail to realize the full potential of the Better Regulation framework.[12] Moreover, the European Parliament has little awareness of the innovation principle, which severely limits its utility.[13]

The European Commission should seize the opportunity presented by the EIA to correct this imbalance, embedding competitiveness and innovation directly into the policymaking process. The Commission should start by reforming existing Better Regulation tools rather than layering on additional, siloed checks. For example, the current mandatory competitiveness check assesses against four key metrics: cost and price competitiveness, capacity to innovate, international competitiveness, and SME competitiveness. In practice, most competitiveness assessments focus on the internal market and SME impact, with insufficient clarity as to which level of competitiveness the Commission is assessing, such as at EU, Member State, regional, sectoral, or firm level.[14] Such an approach reinforces a “pro-SME culture,” and an inward-looking, inconsistent approach to competitiveness.

The Commission should reform the competitiveness check metrics to mandate equal consideration of all costs. First, to ensure size-neutral innovation policy, the Commission should replace its “SME competitiveness” check with a broader “firm competitiveness” check to ensure regulation does not affect the necessary contributions of larger firms’ innovation to the EU. Second, the Commission should require all competitiveness checks to identify any direct or indirect links between regulatory measures and competitiveness drivers such as productivity, as recommended by the RSB that assesses the functioning of the Better Regulation framework.[15]

Similarly, the European Commission should replace the precautionary principle with the innovation principle as the key guiding principle for EU policymaking, ensuring that considerations of competitiveness and innovation are not the sole responsibility of the Commission, but rather are integrated into all aspects of the policymaking process. Placing innovation at the very foundation of the EU, such as within the TFEU, would oblige all EU institutions to focus on tangible benefits when assessing proposed legislation. Such an approach would provide the balance needed to protect Europe’s citizens while also enabling innovation to flourish.

In order to ensure a more innovation-focused approach to regulation, the European Commission should establish an Office of Innovation Review (OIR) within the RSB to serve as an “innovation advocate” in the EU’s regulatory process.[16]

Too often, regulatory review bodies focus on short-term, static effects—such as whether a rule will raise immediate costs—while overlooking longer-term, dynamic impacts on innovation. Indeed, in 2023, the RSB itself called for better, more consistent assessments by the European Commission to link regulation to competitiveness drivers.[17] A dedicated office within the RSB, but with authority to assess not just the European Commission but any EU regulatory actions that affect innovation, would provide the level of consistency needed to realise the EU’s innovation and competitiveness goals. The OIR would have the authority to push agencies to either actively promote innovation or achieve regulatory objectives in ways that are least harmful to innovation.

The Commission should also ensure that this office embeds four core principles into regulatory decision-making: prioritizing innovation as a driver of competitiveness, ensuring risk mitigation measures are based on concrete evidence of harm, supporting innovation at every firm size, and reducing compliance costs that stifle growth. Embedding these principles consistently across policymaking would send a clear signal that the Commission is serious about making Europe a competitive place to innovate.

At the same time, when the Commission proposes regulations that would clearly advance digital innovation, such as mandating the free flow of data within the EU, the RSB should not require an assessment of employment impacts, as this effectively penalizes rules that deliver higher productivity. At a minimum, if employment effects are measured, the RSB should also assess expected productivity and wage gains to offer a balanced assessment.

By taking these steps, the European Commission would give businesses confidence that it understands the building blocks of successful innovation policy. Establishing an OIR within the RSB would not only reduce unnecessary barriers but also create the conditions for European firms to take risks, compete, and grow.

The Commission should also consider that smart deregulation can be an enabler of innovation. A recent report from the Global Trade and Innovation Policy Alliance (GTIPA) highlights examples from multiple European countries of how smart deregulation can unleash innovation in high-tech industries.[18] For instance, Germany promoted online pharmacy competition by removing restrictions on mail-order medicine sales and Italy focused on procedural simplifications to accelerate broadband deployment.[19]

Europe’s lack of a common market means European innovators suffer from considerable regulatory fragmentation, as companies must navigate 27 different sets of laws, taxes, administrative rules, etc. when they do business beyond their home country.[20] Accordingly, Europe should introduce a so-called “28th Regime” that would help European startups scale more efficiently across the continent. It would allow startup firms to:

▪ Incorporate once, and have that status recognized across the whole EU;

▪ Manage taxes, governance, and reporting through a single digital window;

▪ Hire employees, issue stock options, and raise funds across borders more seamlessly without necessitating legal representation or advice in each country;

▪ Startups would be able to incorporate directly under the 28th Regime, with no requirement for a multi-country footprint before formation.[21]

Critically, a 28th Regime wouldn’t supplant or obviate an individual nation’s corporate laws, it would simply provide an alternative pathway for startup companies to incorporate and operate across the European Union.

Like the United States, Europe needs to do a better job at transforming scientific R&D funding into new commercialized innovations in Europe. One way to advance this would be to require that recipients of R&D funding grants under the Horizon Europe program submit a one-pager explaining the potential for technological commercialization of the science they’re examining under the R&D research.

One reason the United States has come to lead the world in innovation is that it has transformed its universities into engines of innovation.[22] In fact, from 1996 to 2020, academic technology transfer activities resulted in 554,000 inventions disclosed, 141,000 U.S. patents granted, and 18,000 start-ups formed.[23] This activity has bolstered U.S. gross domestic product (GDP) by up to $1 trillion and contributed to $1.9 trillion in gross U.S. industrial output. America’s successful academic technology transfer system has been underpinned by the Bayh-Dole Act, federal legislation which gives universities the rights to the IP that stems from federally funded R&D, and which the universities can then license out to entrepreneurs. In fact, nearly 73 percent of U.S. university licensing deals involves startups (quite commonly university spin-offs) or small companies.[24]

Several European nations—including Belgium, Denmark, and Germany—have technology transfer legislation supporting university commercialization of publicly funded research, but there is no European-wide policy in this regard.[25] Europe would benefit from its own Bayh-Dole Act-like framework. But recognizing the subsidiarity challenge here, ITIF applauds the Commission’s plan to develop a blueprint for licensing, royalty, and revenue-sharing and equity participation for European higher education institutions and research-performing organizations when commercializing IP and creating spinoff companies. The European Commission can further work to establish and socialize best practices when it comes to the IP licensing practices of European universities.

The European Commission should also work to advocate for other best practices pertaining to stimulating entrepreneurship activity out of European universities. A global movement called “Promotion & Tenure—Innovation & Entrepreneurship” (PTIE) has emerged to support the inclusive recognition of innovation and entrepreneurship (I&E) impact by university faculty in promotion, tenure, and advancement guidelines and practices.[26] The movement notes, “Academic promotion and tenure (P&T) processes that typically prioritize faculty grants and publications can fail to fully access and value entrepreneurial, innovative endeavours that can produce the kind of societal impacts that universities are increasingly being called upon to provide and that many faculty and students increasingly prioritize.”[27] Certainly, considering professors’ and researchers’ roles in developing patents or other IP or launching start-up companies should become a larger factor in making tenure decisions at European universities. Along these lines, European universities could become more entrepreneurial by enhancing the permeability between academia and industry, such as by extending entrepreneurial leave to faculty (and students) seeking to launch entrepreneurial ventures. Getting more commercialization leverage out of European universities is certainly attainable, as one study by the European Patent Office found that only about one-third of the patented inventions from European universities are commercially exploited.[28]

Europe badly trails the United States (and increasingly China) in access to risk capital. In fact, from 2013 to 2022, venture capital (VC) raised by VC firms headquartered in the United States outstripped VC raised by European-headquartered VC firms by $1.2 trillion.[29] Annual VC investments in the European Union averaged just 0.2 percent as a share of EU GDP from 2013 to 2023, compared with a U.S. average of 0.7 percent.[30] This paucity of VC helps explain why by the time they reach 10 years in operation, European scale-ups have raised on average 50 percent less capital than their San Francisco peers. Further, more than 50 percent of late-stage investment in European tech companies comes from outside the EU, making European startups dependent on foreign capital.

To deepen access to risk capital, Europe should reform its rules governing public pensions to permit pension funds to invest a fraction of their investments into VC companies, something which is permitted in the United States but not in Europe. Eight years after allowing U.S. pension funds to invest in risk capital, such as VC, the share of pension funds in VC increased from 15 to more than 50 percent.[31] More than 60 percent of European household investments remain within their home country, limiting cross-border capital flows across Europe; reforming pension investment controls could facilitate greater movement of capital across Europe.

In the EU, most pension funds are managed at the national level, complicating broad reform across Europe. Rather than implementing sweeping changes across Europe, the European Commission should initiate an effort to document all national pension investment frameworks across Europe and provide recommendations on a national basis, encouraging the deregulation of investment capabilities.[32]

Increasing access to risk capital requires greater investment in the European Investment Fund (EIF) and European Investment Bank (EIB). National governments and the EU should increase capital contributions to the two lending institutions, and the European Council should act to remove the lending limit placed on the EIB. The gearing ratio, which was amended earlier this year, has increased to 290 percent of the bank’s capital, allowing for greater risk-taking.[33] However, removing the cap altogether will enable the EIB to increase its lending ability in the future without the need for future adjustments to the gearing ratio, allowing the bank to undertake more investments.[34]

The EU should also reduce restrictions on who may invest in large VC funds exceeding €500 million. Under the Alternative Investment Fund Managers Directive (AIFMD), investors must meet the full authorization requirements to become an AIFM, a process that is lengthy and costly. Additionally, the funds must meet capital adequacy and disclosure reporting requirements, must appoint a depository bank to oversee fund assets, and must undergo much more regulatory scrutiny than required for funds under €500 million.[35] These regulations increase the cost of running a VC fund, even though the risk is similar for a fund of €100 million and €500 million. Implementing the existing standards of the EU Venture Capital Funds Regulation (EuVECA) for larger VC funds would reduce the cost and barrier to entry for investors in these larger funds.

In the recently approved European Union Council document on “The importance of research and innovation for the EU Startup and Scaleup Strategy,” the Council “Stresses the important contribution of private and public funding to reach the 3% GDP target for R&D.”[36]Indeed, Europe is underinvesting in R&D. Consider that of the top 100 (out of the top 2,500) R&D-investing firms in the world, America’s top 100 R&D investors invested €16.6 billion in R&D in 2024, while European firms invested just €3 billion. For the top 500 R&D-investing firms, American ones invested €21.8 billion, while European firms invested just €5.7 billion, a nearly four-fold gap.[37]

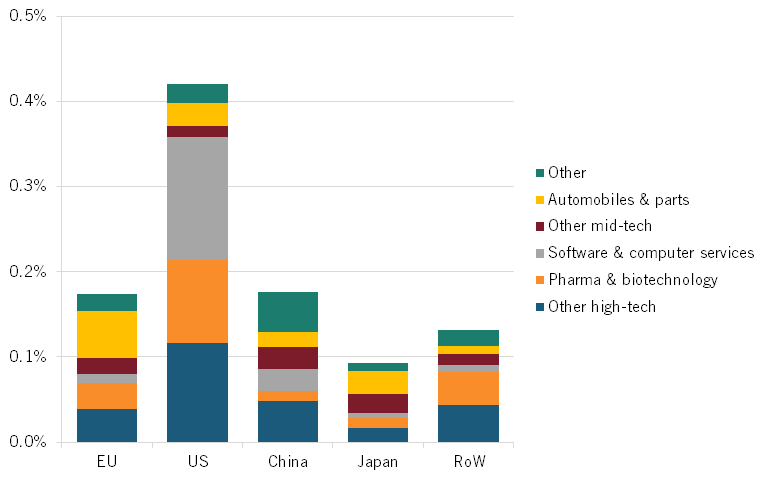

This matters especially because Europe is caught in a “middle technology trap.” Examining the R&D investments of European firms among the top 2,500 European R&D investors by sector, automobiles and auto parts received the highest share, at 0.6 percent of total R&D investment of those firms. By comparison, in the United States, software & services received the highest share of total R&D investment by the top 2,500 R&D-investing firms, with a 0.14 percent share, followed by other high-tech (0.12 percent), and pharmaceuticals and biotechnology (0.10 percent).[38] (See figure 1.) In other words, U.S. firms are investing much more R&D into cutting-edge technology areas (e.g., AI, quantum, biotechnology, etc.) than are European ones.

This in part explains why one study finds EU countries and the United Kingdom account for just 2 percent of the cumulative share of AI patents granted globally, while the United States accounts for 21 percent and China 61 percent.[39] In short, it is imperative that Europe’s public and private sectors invest more in R&D and that the continent invest more risk capital into cutting-edge industries.

Figure 1: Business R&D investment by sector (top 2,500 R&D investing firms, by country, 2024)[40]

The EIA is a necessary, but insufficient, initiative to address the EU’s competitiveness challenges. The European Commission should not let the EIA become another incremental initiative that tinkers at the edges of Europe’s competitiveness challenge. The EIA focuses on improvements that do not solve the continent’s structural weaknesses. Instead, the Commission should rethink Europe’s entire regulatory posture. If the EU continues to prioritize hypothetical risks over tangible benefits, European firms will remain slower, smaller, and less competitive than their American and Chinese counterparts.

The Commission should use the EIA to place innovation at the bedrock of EU policymaking. Without these steps, the EU risks permanently falling behind its rivals.

Thank you for your consideration.

[6]. Article 191 Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union.

[14]. Ibid, footnote 10.

[17]. European Commission, “Regulatory Scrutiny Board Annual Report 2023.”

[26]. “Valuing Societal Impact in Higher Education” (Promotion & Tenure—Innovation & Entrepreneurship), https://ptie.org/.

[40]. European Commission, “Science, research and innovation performance of the EU, 2024.”