Lorraine Jacob’s body was found in the city centre in 1970 Lorraine Jacob was found dead on September 2, 1970 in Liverpool(Image: PA)

Lorraine Jacob was found dead on September 2, 1970 in Liverpool(Image: PA)

Last month marked 55 years since a mum was found dead in an alleyway, sparking a murder investigation that lasted for decades. Lorraine Jacob, 19, was last seen walking alone along Pilgrim Street towards Hardman Street in Liverpool city centre at around 11pm on Tuesday September 1 1970.

Lorraine lived on Russell Street with her mum, her 14-month-old daughter and her baby boy. She was seen drinking in Yates’s Wine Lodge in Great Charlotte Street at 9pm. Lorraine was seen again in a Chinese chip shop in Great George Street at 10.20pm before walking up Upper Duke Street.

Her body was found the next day by council binmen in a small entry at the back of the Young Women’s Christian Association in Rodney Street.

The entry was off another alley which ran between the YWCA hostel and St Andrew’s Scottish church.

A Home Office pathologist had put an estimated time of death of around midnight and no later than 1.30am.

Officers investigating her murder took more than 900 statements and put out 3,500 questionnaires around pubs, clubs and homes, but no culprit could be found. The case lay mainly dormant for decades, with periodic reviews from time to time.

It was until 2008 that it emerged that Lorraine’s killer had been found thanks to a crucial piece of evidence in an unlikely place.

The major break-through came when 78-year-old Harvey Richardson died in a Wigan hospice from bowel cancer.

As decorators cleaned out his house, they discovered a brown leather satchel and on rummaging inside the bag, found an envelope marked “private and confidential”.

Inside was a detailed, handwritten confession to Lorraine’s murder in black ink on nine pages of yellowing A4 paper.

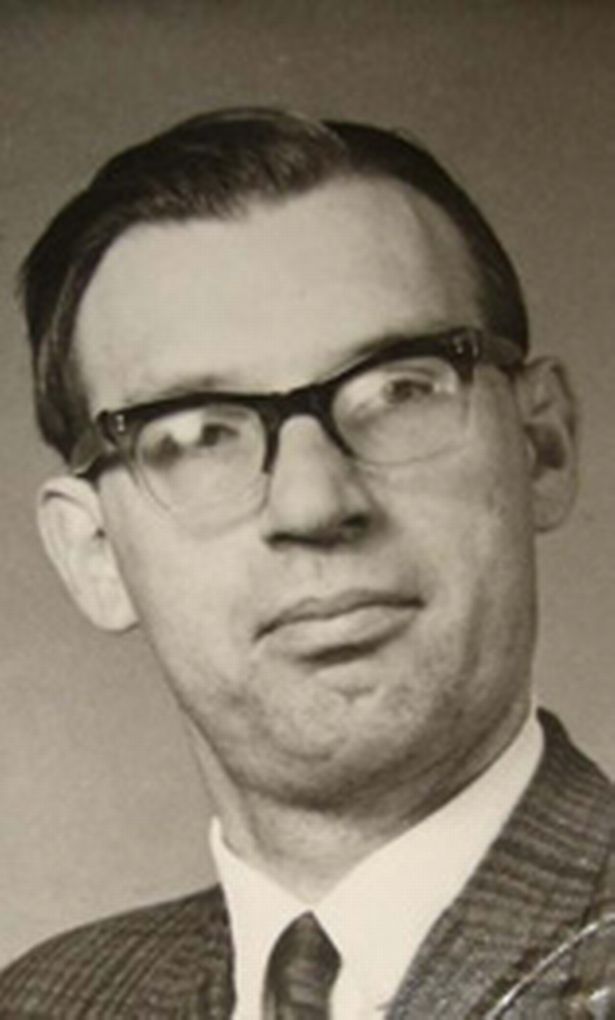

Harvey Richardson, who confessed to the murder(Image: Handout)

Harvey Richardson, who confessed to the murder(Image: Handout)

With the unsigned and undated note was a large collection of press cuttings relating to the killing and a pair of blue knickers which belonged to Lorraine and were missing when her body was found.

The decorators also uncovered an antique air pistol and called in Cheshire police, who on recognising the possible significance of the find, called their Merseyside counterparts.

When detectives went through the confession, it revealed, in great detail, how Lorraine had died and more importantly why. Paper age analysis points to the letter being written and sealed in the envelope shortly after the murder.

It also contained facts that had never been in the public domain. Richardson was never a suspect in the original investigation and had never come to the police’s attention for anything.

The eloquently written 26 paragraphs, said to read more like a story than a confession, detail how a drunken Richardson met Lorraine on Pilgrim Street shortly after 11pm on Tuesday September 1, 1970.

She was clutching three bags of chips she had bought after a night out and was making her way home. He had been out all day drinking in various city centre pubs to drown his sorrows after learning he had failed his college exams to become a librarian.

They walked to Rodney Street and down an alleyway, where police say an argument broke out. In a fit of rage, Richardson strangled his victim and dropped her body to the cracked paving flags below.

In his drunken state, he ripped off her brown tights and blue knickers and took her purse from her handbag.

Council binmen found Lorraine’s body the next morning, her skin ravaged by the overnight rain and the soggy bags of chips still by her side.

With her back on the pavement, police found the ground underneath her coat was dry, putting her time of death before the rain began at 3am that morning.

Police believed it was over a photograph of her children that Lorraine and Richardson, who moved to Liverpool to try and work as a librarian, came into contact.

Richardson was born on December 10, 1930, in Littleborough, a small suburb of Rochdale at the foot of the South Pennines.

He spent his formative years in Rivington, near Bolton, where his dad worked in the local hospitals as a chest surgeon and radiologist and his mum looked after him.

Richardson suffered from mental health issues throughout his life.

In mid-June 1970, a few months before her murder, Lorraine and a friend went to a flat Richardson was renting in a house on Huskisson Street, on the edge of Toxteth and the city centre.

He was out but the pair were allowed into the communal area before going into his bedroom and taking two cameras.

From a witness who came forward after the case was re-opened, it is believed some time before the cameras were taken Richardson had taken a picture of Lorraine’s children and the pair had rowed over it.

But police could not say when or why the picture was taken although they have said they do not believe it was anything sinister.

When Richardson returned home and discovered his cameras gone, he was told of the two women callers and immediately knew who it was.

But it is thought the paths of killer and victim did not cross again until that fateful chance meeting late at night two-and-a-half months later.

In the confession, Richardson spoke of losing his temper with Lorraine over the cameras and he took her purse because it contained a ticket for a pawn shop.

But he never went to Biggars Pawn Shop, in the city centre, instead tearing up the ticket and flushing it down the toilet. He cut up the leather, semi-circle purse into small pieces and threw it away.

In the note, he wrote of hanging the brown tights on a branch in Sefton Park, close to the Greenheys Road flat he took on after being kicked out of Huskisson Street in late July 1970, but he kept hold of the blue knickers.

The nine-page confession recounts his movements of that day, with the last page detailing him returning home after killing Lorraine by strangling her.

That detailed knowledge of the crime, along with DNA matches to both Lorraine and Richardson found on the knickers, led to the decision to close the case.

The case was officially closed in 2009. Colin Davies, head of the Crown Prosecution Service’s complex case unit, said at the time: “Following the forensic evidence and the thorough investigation by the police, I decided there was sufficient evidence to justify a prosecution in the case of Harvey Richardson for the murder of Lorraine Jacob in the event that he was still alive.

“Were he alive, he would, of course, be entitled to a fair trial and it would be for a court to decide whether the prosecution had proved the case beyond reasonable doubt.”