A huge asteroid came within 300 miles of hitting Earth, and scientists only noticed after it had already skimmed past the planet.

The 9.8-foot (three metre) space rock, dubbed 2025 TF, flew over Antarctica in the early hours of October 1.

Passing at an altitude of just 265 miles (428 kilometres), the rock came closer to the Earth’s surface than the orbit of the International Space Station.

However, space agencies only realised the near-miss had occurred when the asteroid was detected by the Catalina Sky Survey a few hours later.

While a miss this close might sound alarming, the European Space Agency (ESA) claims there was never any serious danger.

Based on its estimated size, 2025 TF would have most likely burned up or exploded in the atmosphere rather than slamming into the surface.

ESA said in a statement: ‘Objects of this size pose no significant danger.

‘They can produce fireballs if they strike Earth’s atmosphere, and may result in the discovery of small meteorites on the ground.’

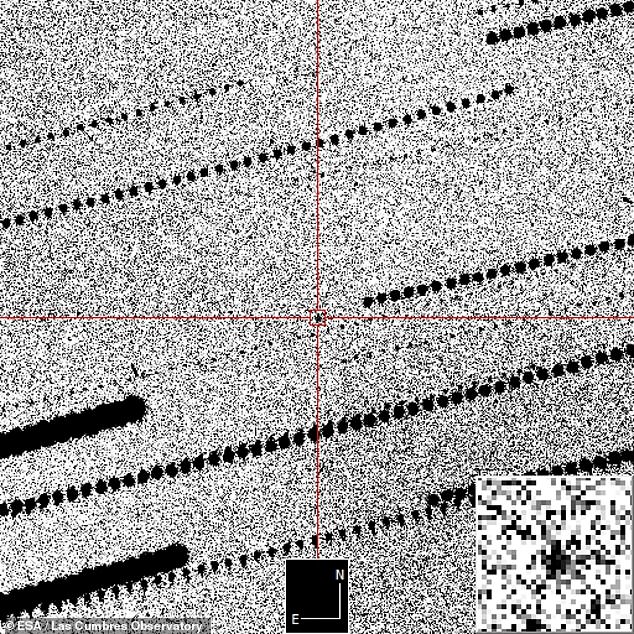

A huge asteroid passed within 300 miles of Earth, but astronomers only realised the close encounter had happened when telescopes picked up the asteroid hours later. Pictured: Image of the asteroid taken by the Las Cumbres Observatory

After the asteroid passed, astronomers at the ESA’s Planetary Defence Office observed it using the Las Cumbres Observatory in Australia.

This allowed for a more accurate estimate of the object’s size and worked out that it had reached its closest point to Earth at exactly 01:47:26 BST.

ESA says: ‘Tracking down a metre-scale object in the vast darkness of space at a time when its location is still uncertain is an impressive feat.

‘This observation helped astronomers determine the close approach distance and time given above to such high precision.’

While it might not have done much damage to the planet, even a small space rock could have caused serious damage to a spacecraft.

This is particularly concerning since 2025 TF passed within the orbit of the ISS.

However, there were thankfully no spacecraft or satellites in the way as this asteroid passed.

Although NASA has paused all public communication during the government shutdown, the space agency has created an entry for 2025 TF on its Center for Near-Earth Object Studies website.

The asteroid, dubbed 2025 TF, passed 265 miles (428 kilometres) above Antarctica in the early hours of October 1. This put it at roughly the same altitude as the International Space Station (stock image)

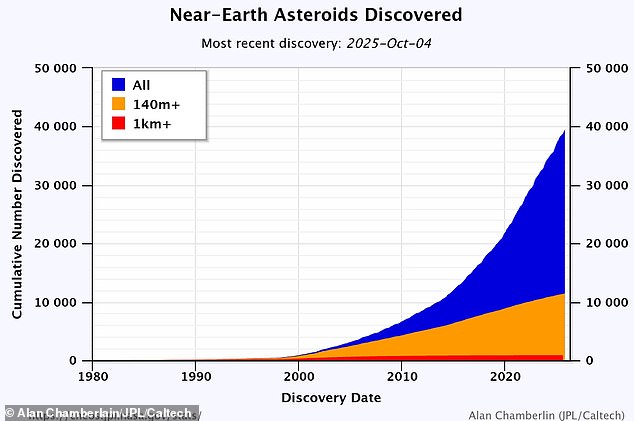

How many Near Earth Asteroids have been detected?

Total: 39,585

Over 140 metres: 11,453

Over 1 kilometre: 877

Figures as of October 4, 2025

According to this entry, the asteroid will next return to Earth in 2087 when it will pass within 3,710,795 miles (5,971,946 km) of the planet.

However, to be classed as a ‘potentially hazardous’ asteroid, a space rock must have a diameter of at least 460 feet (140 metres) and follow an orbit that will take it within 4.65 million miles (7.48 million km) of Earth.

Although 2025 TF’s orbit takes it well within this distance, it is simply too small to be considered a hazard.

This small size also makes it extremely difficult to spot, which likely explains why it wasn’t noticed until it had already passed Earth.

Each year, space agencies around the world discover thousands of so-called near-earth asteroids (NEAs).

These range from relatively harmless space rocks like 2025 TF to enormous ‘city-killers’ like the asteroid 99942 Apophis.

As of October 4, there were 39,585 known NEAs, including 11,453 asteroids larger than 460 feet (140 metres) in diameter.

Of these, about 2,500 are considered potentially hazardous, according to the International Astronomical Union’s (IAU) Minor Planet Center.

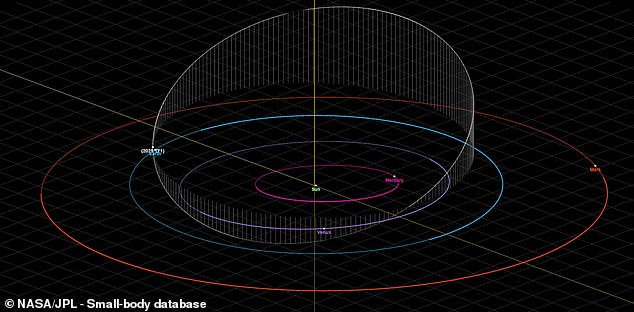

2025 TF measures up to 9.8 feet (three metres) in diameter. Even though its orbit (illustrated) took it close to Earth, it is too small to be considered a potentially hazardous object

Each year, astronomers find thousands of Near Earth Asteroids (NEAs), many of which are over 460 feet (140 metres) in diameter. However, there are currently no objects that pose a risk to Earth in the next 100 years

These hazardous space rocks are subject to a much higher level of scrutiny, and their orbital paths are carefully calculated to see if they will hit Earth.

But, as this near miss demonstrates, even the world’s most sophisticated planetary defence systems can’t capture anything.

While scientists expect that almost all city or planet-killer asteroids will be detected long before they arrive, small but dangerous asteroids can still slip through.

In January last year, NASA’s Scout impact hazard assessment system alerted authorities to a six-foot (two metre) asteroid heading towards Berlin just 95 minutes before it impacted.

Most famously, in 2013, residents of the Russian town of Chelyabinsk witnessed a 66-foot (20 metre) asteroid explode less than 19 miles (30 km) above the surface.

Scientists hadn’t seen the asteroid at all since it was approaching from the direction of the sun and couldn’t be seen during the day.

However, the blast released 30 times more energy than the atomic bomb dropped on Hiroshima, destroying 7,200 buildings and sending 1,500 people to the hospital.

Since this time, planetary defence systems have greatly improved, but many scientists still think more work needs to be done to ensure similar asteroids aren’t missed in the future.

WHAT COULD WE DO TO STOP AN ASTEROID COLLIDING WITH EARTH?

Currently, NASA would not be able to deflect an asteroid if it were heading for Earth but it could mitigate the impact and take measures that would protect lives and property.

This would include evacuating the impact area and moving key infrastructure.

Finding out about the orbit trajectory, size, shape, mass, composition and rotational dynamics would help experts determine the severity of a potential impact.

However, the key to mitigating damage is to find any potential threat as early as possible.

NASA and the European Space Agency completed a test which slammed a refrigerator-sized spacecraft into the asteroid Dimorphos.

The test is to see whether small satellites are capable of preventing asteroids from colliding with Earth.

The Double Asteroid Redirection Test (DART) used what is known as a kinetic impactor technique—striking the asteroid to shift its orbit.

The impact could change the speed of a threatening asteroid by a small fraction of its total velocity, but by doing so well before the predicted impact, this small nudge will add up over time to a big shift of the asteroid’s path away from Earth.

This was the first-ever mission to demonstrate an asteroid deflection technique for planetary defence.

The results of the trial are expected to be confirmed by the Hera mission in December 2026.