More private than a Catholic confessional and more intimate than a peep show, the analogue photo booth turns 100 this year. And to celebrate, The Photographers’ Gallery in London is hosting a four-month survey with a small, special archival display that turns the camera on the mini-studios where billions have sat, whether for fun or function.

Running until 22 February, Strike a Pose! 100 Years of the Photo Booth begins with an origin story. In 1925, when Anatol Josepho debuted the world’s first automated analog photo booth on Broadway and 51st Street, 7,500 New Yorkers had a go in the first five days and 280,000 within the first six months. By the 1990s, with the rise of digital photography, they had virtually disappeared and today there remain fewer than 200 photo booths globally.

La relique, Prague. © 2025 Fotoautomat.

Le Mutoscope, Galeries Lafayette Champs Élysées. © 2025 Fotoautomat.

Le Lieu Unique, Nantes. © 2025 Fotoautomat.

The Palais de Tokyo, Paris. © 2025 Fotoautomat.

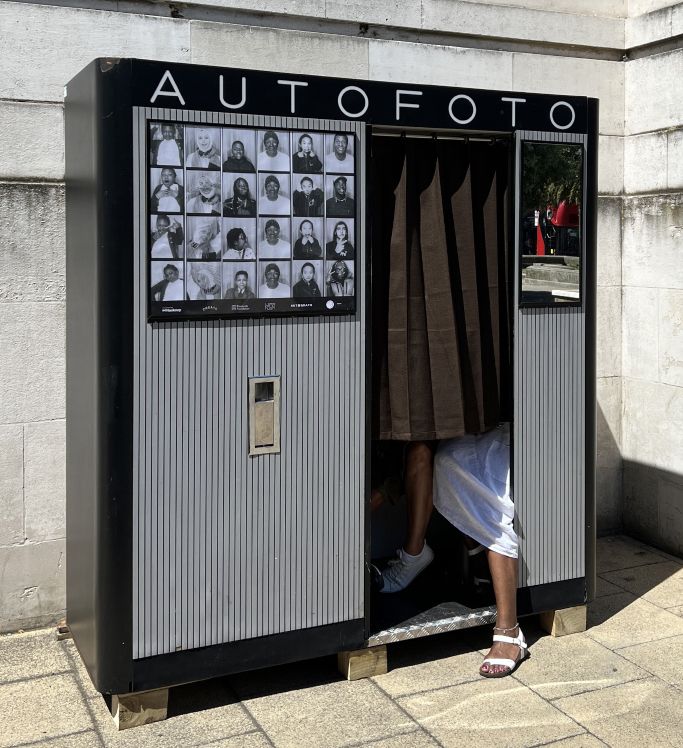

Autofoto. © Courtesy Autofoto.

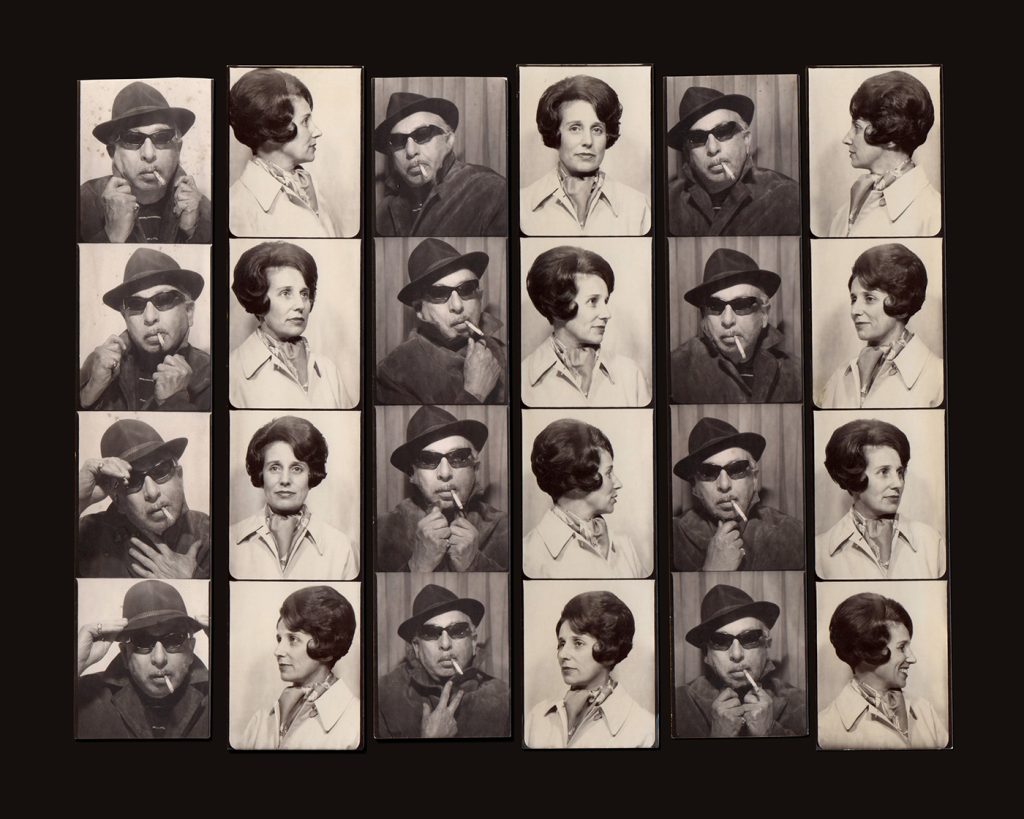

French Couple, Six Strips, 1960s, France. © Courtesy Raynal Pellicer.

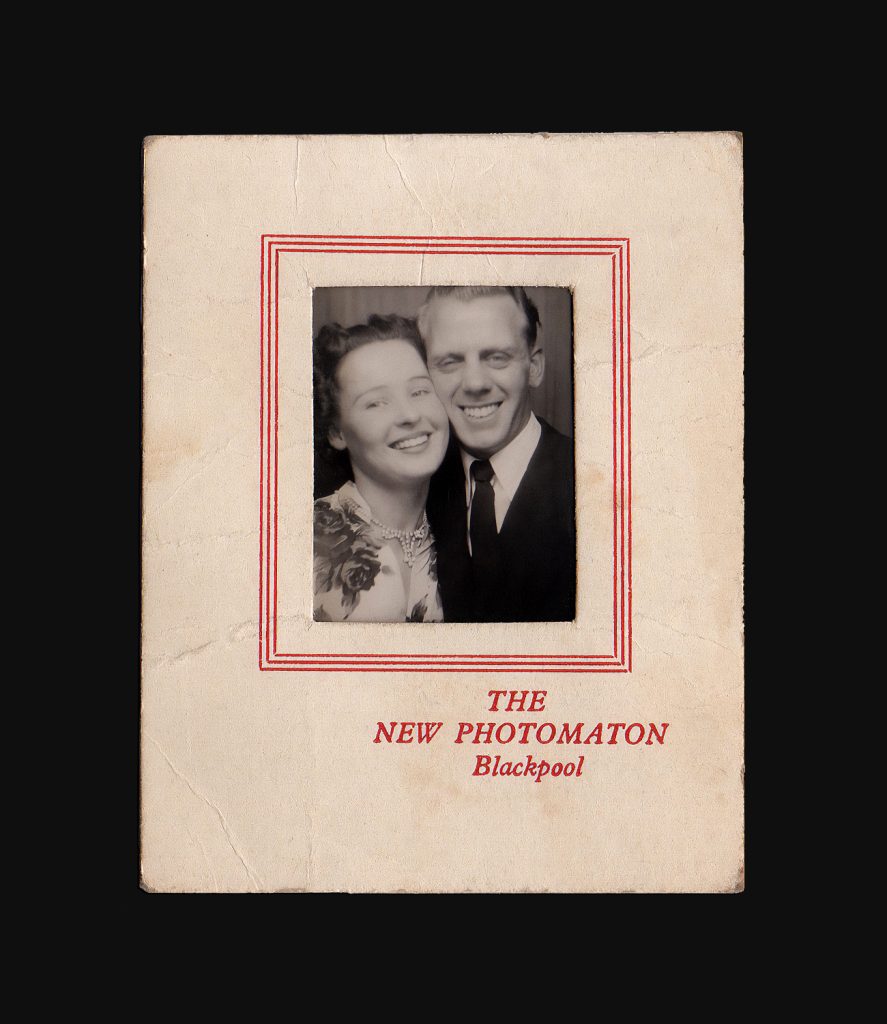

Couple, Photomaton, 1950s. Blackpool. © Courtesy Raynal Pellicer.

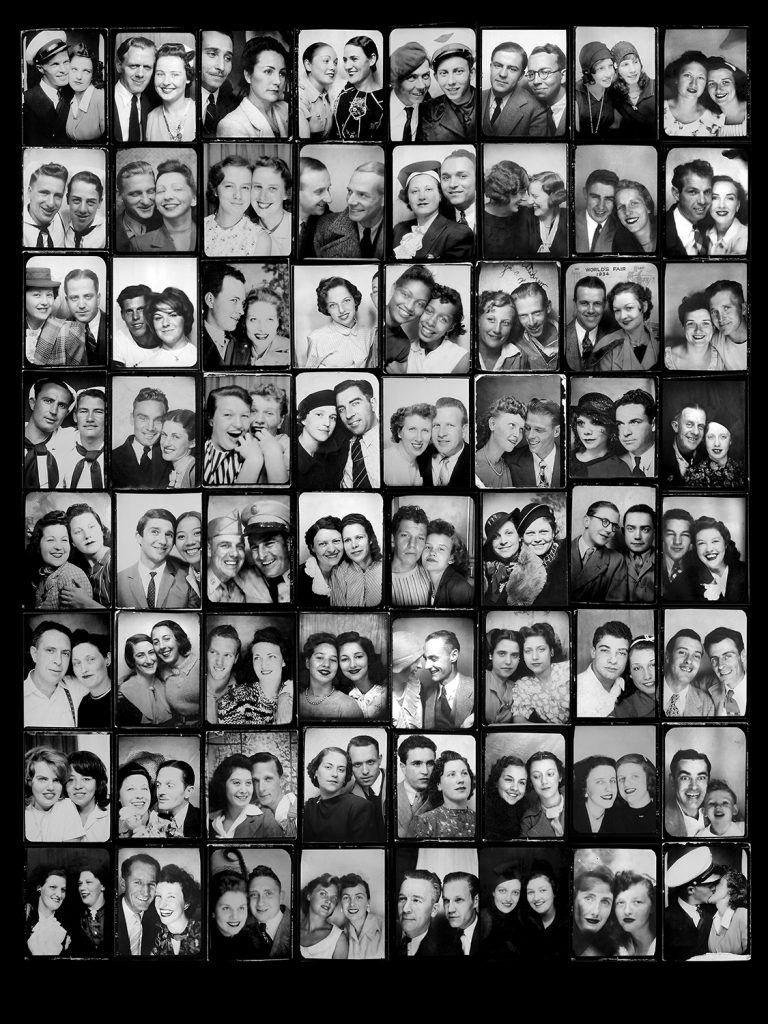

Couples, circa 1930s-1950s. © Courtesy Raynal Pellicer.

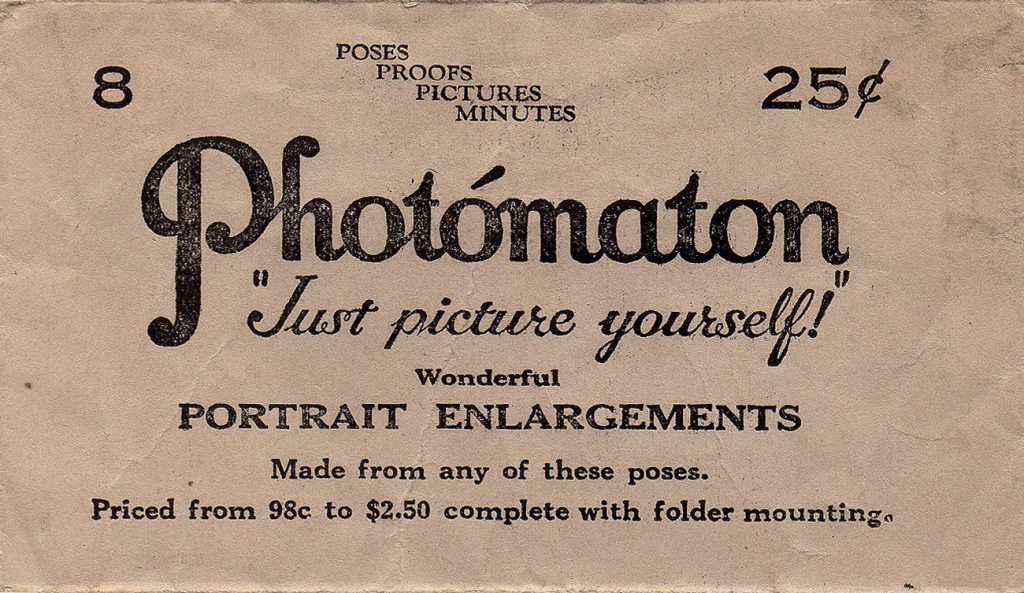

Photomaton Envelope, 1940s. © Courtesy Raynal Pellicer.

The London- and Barcelona-based company Autofoto came to the rescue in the 2000s, buying up, restoring and souping up old booths to preserve the vanishing culture. ‘Our aim is to have them in publicly accessible places — hotels, shopping centres, arts venues and hopefully train stations,’ says creative director Corinne Quin, ‘so they reflect and respond to the rhythms of the communities around them.’ Ultimately, Autofoto sponsored the Photographers’ Gallery exhibition. And recently the company collaborated with photographer Tara Darby to snap an entire primary school in the London Fields neighbourhood for posterity. ‘The technology has hardly changed since the 1940s, so images people take today are comparable with those from more than 60 years ago,’ says Quin. Yet the ‘digital generation brings their own creativity and perspective’.

Battersea Power Station, London. Image Auto Foto.

The photo booth’s architecture — a boxy two-square-metre footprint, controlled lighting, a thin curtain to pull shut — is a threshold space, somewhere between the private and public realms. As urban life becomes increasingly surveilled, the slow tactility and spontaneity of these booths feel increasingly precious. ‘Just yesterday we had a marriage proposal,’ says Eddy Bourgeois of Fotoautomat France, an Autofoto contemporary. ‘These same people tend to come back years later with their strollers and continue the joke with their children.’

Behind the curtain people, alone or not, can experiment with portraiture without the need of a photographer. Some seek to commemorate important events or faces, others pursue a thrill only public secrecy affords. ‘Some have even tried to copulate in there,’ says Bourgeois, ‘probably because it’s cheaper than a hotel room in Paris — maybe more fun, too.’

Portrait of Anatol Josepho in his Photomaton, 1927, USA. © Courtesy Raynal Pellicer.

Photography: Memphis, LE CITADIUM. © 2025 Fotoautomat.

Read next: We explore the second edition of We Design Beirut with its founder

How to use art as a design tool, according to the experts

A new event throws a spotlight on collage