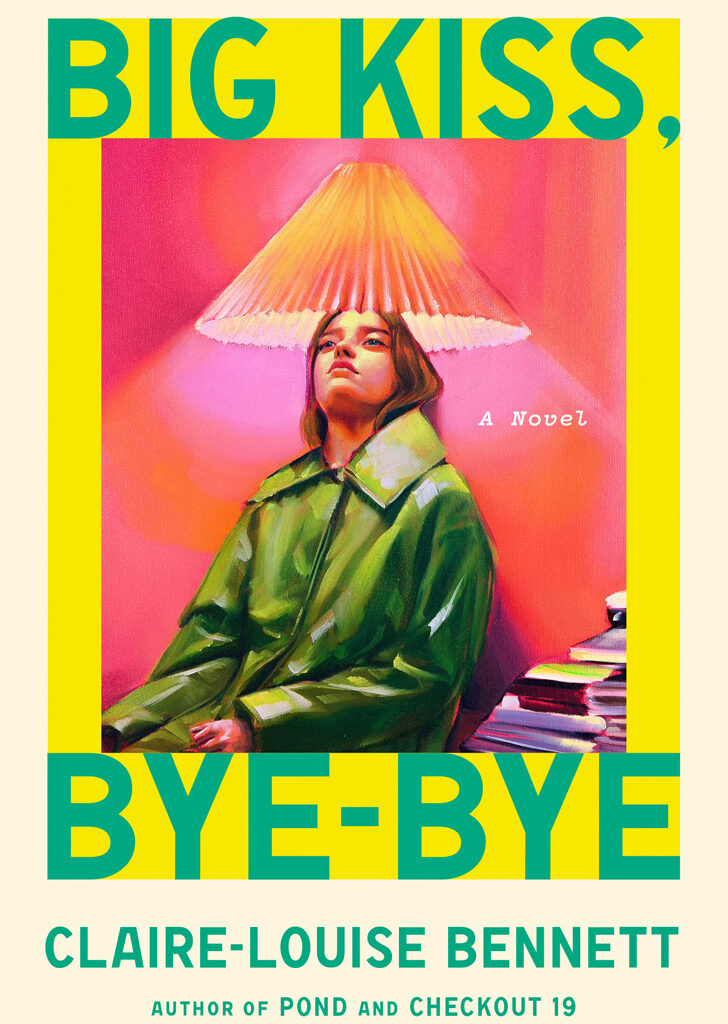

Big Kiss, Bye-Bye

Jessi Jezewska Stevens

A setup familiar to contemporary fiction and romance ends up defying expectations in the latest novel by Claire-Louise Bennett.

Big Kiss, Bye-Bye, by Claire-Louise Bennett,

Riverhead Books, 209 pages, $29

• • •

It’s a typical story. The woman, in the bloom of youth, arrives for dinner. The man, her senior, is already waiting inside. She’s taken care with her appearance (“He likes to see women dressed up”), though the relationship is in decline. Then comes the twist: she’s written a book—wait for it—a copy of which she attempts to slip into the bag hanging from “a handle on his wheelchair.” Emphasis mine.

The British novelist Claire-Louise Bennett, author of two previous works of fiction, Pond and Checkout 19, has won critical acclaim for her stylized treatments of the domestic sphere and the writing life. Autofictional source material—a broken oven knob; searching for an apartment as a struggling cashier—is elevated to high drama through baroque rumination. These are solitary books, with umbilical cords fixed to the previous century. The signature, antiquated syntax is tempered with sly colloquialisms (“I do not know fully what drove me to deracinate thick and fuzzy weeds like that every day in the premature heat,” muses a discouraged gardener in Pond, if not the rumor that doing so would be a “cinch”), while literary allusions take precedence over secondary characters. The cashier in Checkout 19 reads the classics at her supermarket post while dreaming of becoming a writer herself; her chosen foil, the working-class British novelist Ann Quin, now deceased, is as alive and dynamic as any acquaintance. The power of this introspective mode lies less in the plot than in long-delayed moments of epiphanic anger: “It made our blood boil to read that,” the clerk declares upon learning how many British students are pressed to “flatten” their accents. “Imagine someone day in day out purposefully making you feel ashamed of the sound of your own voice.”

Big Kiss is a departure in structure if not in style: it has plot—or at least a central relationship. The man in the wheelchair is Xavier, a former “private banker” who has become “more or less bedbound” due to his advanced age. Shortly after giving him her book, the unnamed narrator refuses to kiss him, precipitating an unexpected breakup. The COVID lockdown reinforces the sudden separation, shifting the quasi-lovers’ (they haven’t had any “physical engagement” for seven years) fraught postmortem of the relationship onto email. Mutual ill will escalates when Xavier messages to say he found her book, whose contents remain unknown to us, to be “some sort of HELL.” The setup—a mismatch of sexual desire—places us in a quandary much more familiar to contemporary fiction than Bennett’s earlier investigations of class, domesticity, and writing. In a cishet context, can men and women ever be reconciled in matters of sex? Can they ever be just friends?

That the narrator does in fact love Xavier is never in question, which is precisely why his retaliation (the abrupt breakup) hurts so much. “There was a time when I got lost in kissing him for whole afternoons. But not any longer,” she reflects. “And I suppose truth be told that is why he was so unkind about my book.” Sensitive to the fact that age “doesn’t stop him from hurting and wanting,” she wonders what it might mean to have kissed him anyway—against her sexual, if not her emotional, will.

Privacy was essential to the couple’s former eroticism. As if aware their relationship would never survive the public eye, for years they met almost exclusively in secret. The separation forces the narrator to take a closer look at this carefully guarded history. Through email correspondence, journals, dream analysis, and conversations with female friends on pandemic-approved hikes and swims, she uncovers a series of contradictions. “I’m the only one who sees you correctly,” Xavier used to tell her, an “alarming, narcissistic, controlling” claim. “But at the same time isn’t that what anyone wants their beloved to believe?” Conscious his behavior runs counter the reader’s—and possibly even her own—romantic rubrics, she hedges: “I don’t care too much about getting carried away and making a fool of myself. The alternative is to die of boredom.” Besides, his démodé behavior is related to qualities that she finds “repulsed me, and, naturally, turned me on.” Even at his most offensive, Xavier often “just said what most people think but wouldn’t dream of expressing.” As a result, he “was wrong, and he was right.”

This early impartiality delegates indignation to the reader. More uncomfortably, it can leave us in doubt of the heartbroken narrator’s ability to generate any herself. Once, a younger, nimbler Xavier terrified her by climbing into her home through an open window, echoing a previous trauma: years before, a different ex broke in with violent intentions, forcing the narrator to hide, petrified, behind the couch in nothing but a dressing gown. “I bet you looked cute,” Xavier says, with monumental tone-deafness. “I bet I didn’t.” He concedes, “It’s kind of understandable that you don’t like surprises.”

Xavier’s most comical and persistent misfire is to constantly send flowers. The motif becomes an extended Dalloway-ian subplot, as for years unwelcomely ostentatious bouquets arrive on our peripatetic narrator’s ever-shifting doorstep. She once suggested he open an account at the florist, so that she could “go into the shop and choose the flowers [her]self.” Xavier loves idea; it makes him feel like a “rich man again.” Her refined, inexpensive selections, however—she has strong opinions on floral minimalism—are a disappointment. Afraid she’s holding back, he—or is it the florist?—sets a minimum amount: “It became quite stressful and time-consuming having to make it come to fifty euro every time I went in.”

Psychoanalysis hangs like a sword of Damocles over the narrator’s reassessment of the relationship (“Today and yesterday I used A Very Short Introduction to Freud . . . to bludgeon a great many flies . . .”), most notably with her appeals to the “dark sexual fantasies” of Michael Haneke’s film adaptation of The Piano Teacher by Elfriede Jelinek. In the film version of this famously transgressive portrait of female sexual repression, Erika, a forty-year-old Viennese pianist, sadomasochist, and virgin, has her request to be sexually humiliated rejected (humiliatingly) by a much younger male lover. Afterward, she stabs herself in the shoulder, rendering herself incapable of performing. Bennett’s narrator finds the scene triumphant: “I do not perceive in Erika’s actions defeat or destitution” but “a galvanized determination to face up to herself.” To release herself from fantasy. The parallels to Xavier’s own sexual humiliation are obvious—though the genders are reversed.

One night, coming to terms with her own demons, the narrator dreams of smashing a scorpion with yet another book. “The scorpion is a really powerful symbol,” says a friend. The narrator agrees: “Did that mean Xavier is a scorpion?” And is this novel the lethal weapon, a way to finally get him—or at least what he symbolizes—out of her head?

Unlike the stark gender- and age-based asymmetry that critics such as Noor Qasim and Namwali Serpell have noted as a hallmark of contemporary romance—novels marked by legislative malaise, negotiations of power, female self-harm, and heteropessimism—in Bennett’s latest, these now-expected dynamics go slack. The age difference is stretched to such an extreme that Xavier is flawed, but undeniably vulnerable. As a result, the question of who has exploited whom, and of how to treat one another in love (or heartbreak), becomes an open one, even if its answers remain painful and ambiguous.

A starker directionality to the couple’s relationship might have led Big Kiss toward more violent romantic implosions, like the piano teacher’s decision to stab herself. Unlike Erika’s dagger, however, or Xavier’s juvenile insults (“some sort of HELL”), Bennett’s anger-laced affection carries the novel beyond self-defense or -destruction. Spoiler alert: sometimes neither party gets what they want, and so the knife is replaced by that much more tender murder weapon, the long-awaited goodbye “kiss.”

Jessi Jezewska Stevens is the author of the novels The Exhibition of Persephone Q and The Visitors. Her debut story collection, Ghost Pains, was a finalist for the 2025 Story Prize.

A setup familiar to contemporary fiction and romance ends up defying expectations in the latest novel by Claire-Louise Bennett.