The UK has entered a fiscal ‘doom loop’. Excessive spending has widened the budget deficit and attempts to narrow the deficit with higher taxes are proving counter-productive by depressing confidence, growth, and revenues. Meanwhile, government structural policies, including on energy and Brexit, are also growth-negative and as a result are adding to the fiscal malaise.

Hardly a day goes by without news stories about how the UK government needs to sharply raise taxes in the face of a growing budget deficit. At the same time, the news is also full of stories about weak UK growth. The two are intimately connected. The UK has entered a fiscal ‘doom loop’ whereby attempts to correct the fiscal deficit with tax increases fail because they depress growth and government revenues.

This outcome should not come a surprise. There is a large body of evidence that suggests that attempting a fiscal adjustment by raising taxes has a low chance of success. Studies past fiscal adjustments find that successful adjustments have had a 70%-75% share of spending cuts and that if the share drops to 40%-50% adjustments are likely to fail or even be reversed (see here and here). Historical examples of successful revenue-driven adjustments are rare. Tax rises tend to blunt incentives and push up prices and wage costs, depressing confidence, investment and international competitiveness.

Recent UK experience is in line with the international evidence. The successful fiscal adjustment undertaken from 2010-2019 (after the global financial crisis) was supposed to be based on a ratio of 80% spending cuts to 20% tax rises. But in practice, the share of revenues in GDP in 2019 was basically the same as in 2010 – the revenue rises never really materialised. All the work was done by the spending cuts, with spending dropping from 46% of GDP to 39%, i.e. back to pre-financial crisis levels.

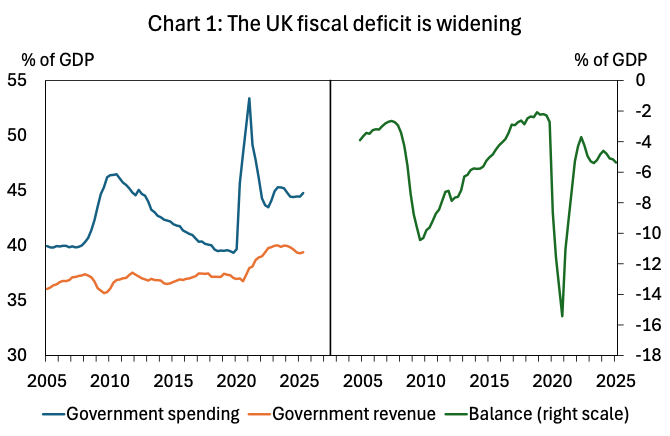

The UK was again in need of fiscal adjustment after government spending soared during the pandemic, but efforts in this area have stalled badly since late 2023. The incoming government in mid-2024 inherited a budget deficit of around 4.5% of GDP, which has subsequently widened to around 5.5% of GDP. Spending has been rising as a share of UK GDP while revenue has been falling – despite a substantial rise in taxes in the October 2024 budget (See Chart 1).

The UK fiscal situation now looks very worrying. The primary (non-interest) deficit is in substantial deficit, and the effective interest rate on government debt is threatening to rise above the rate of growth of nominal GDP, implying an ever-rising ratio of debt to GDP.

Taking into account the negative net interest margin the Bank of England is earning on its government debt holdings, the effective interest rate the government is paying on its debt is around 4%. Nominal GDP growth has been rising faster than this recently, keeping a lid on the deb/GDP ratio. But with trend real GDP growth of at best 1.5% and an inflation target of 2%, this won’t last. The average interest rate on government debt will also rise further as new debt is issued because government borrowing costs are now well above the effective rate payable on government debt.

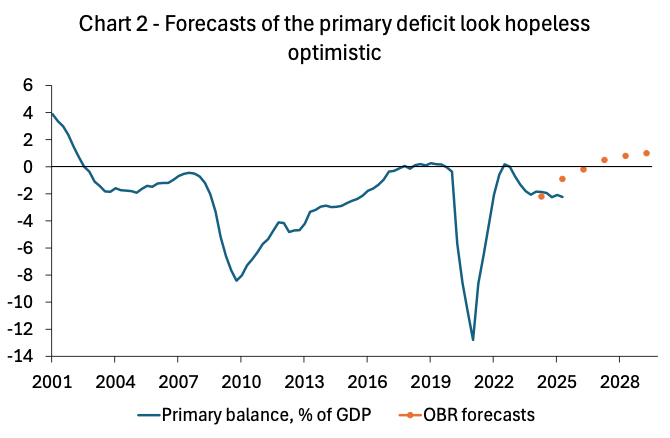

In this situation, the only thing that can stop the debt/GDP ratio rising relentlessly is if the government runs a primary (non-interests) budget surplus. But the government is nowhere near doing this. The primary deficit has been widening recently and is over 2% of GDP. The OBR forecasts a big improvement in the primary balance in the years ahead but its forecasts already look hopelessly optimistic (see Chart 2) – and will not be helped by a likely downward revision to their assumptions about productivity growth.

The problematic fiscal situation is also feeding into declining financial market, consumer, and business confidence.

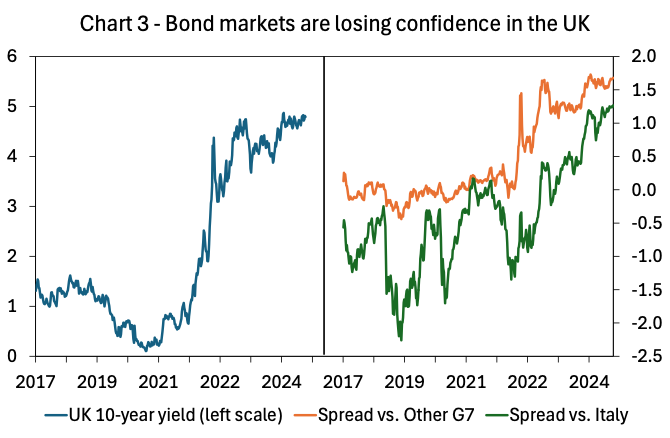

Bond yields have risen globally since 2022, but the UK’s have risen particularly fast. UK 10-year yields are now around 4.7%, up from around 4% in late September 2024 i.e. just before the last budget. The ‘spread’ between their current level and the average level in the other G7 economies is 1.7 percentage points, up from around 1.25 percentage points in September 2024.

This suggests that rather than boosting market confidence, the fiscal adjustment efforts of the current government so far have actually eroded it. Indeed, it is quite striking that the UK is now paying 1.3 percentage points more to borrow money for ten years than Italy, traditionally the large European country with the lowest market credibility. For much of the last decade or so, UK borrowing costs have been well below the Italian level (see Chart 3).

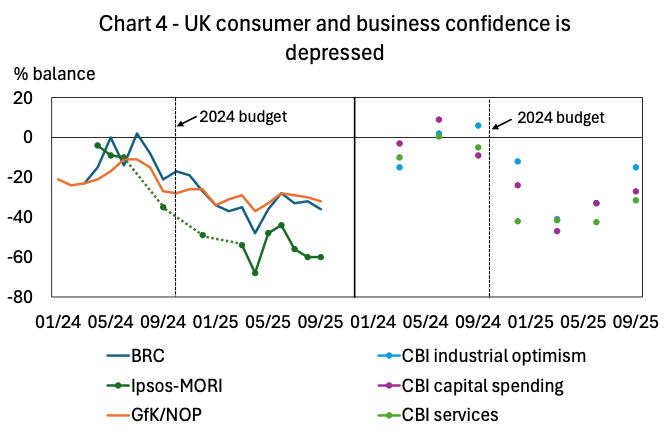

The UK’s fiscal failures have also fed into depressed private sector confidence. Actual and threatened tax rises have contributed to consumer confidence trending down since the 2024 budget across three well-known measures. The long-running Ipsos-Mori measure is close to its lowest-ever levels since 1978. The CBI industrial and services surveys show that business confidence has also collapsed since last year’s budget (see Chart 4). All this points to weak consumer spending, investment, and GDP growth ahead – and thus more downward pressure on government revenues.

From the above, we can see that the government’s attempts to rein in the fiscal deficit via tax rises have comprehensively failed and have left the UK in a vulnerable situation. Is there a way out of this?

The answer is yes, but what is required is a strong adjustment effort centred on expenditure restraint in line with the international evidence. The adjustment doesn’t need to be as large as the one after 2010 (around 3% of GDP would be enough) and would be less painful as a result. Indeed, if it is seen as credible, it could help take out some of the premium that has been built into UK bond yields, which would be a positive factor for the economy. It’s also possible that a credible adjustment might give private sector confidence a modest boost by removing the threat of future large tax hikes.

Ideally, a strong and credible fiscal adjustment would also be accompanied by growth-enhancing structural policies. Unfortunately, the majority of government policies in this area are doing the reverse – actually damaging long-term growth prospects. As we have previously shown, energy policy has given the UK some of the highest industrial energy prices in the world and is leading to rapid deindustrialisation and the run-down of high-wage, high productivity sectors like chemicals, pharmaceuticals and oil and gas.

In addition, planned changes to labour market regulations are also likely to be growth negative, and the government’s ‘reset’ with the EU will lead to at best trivial economic gains and more likely actual net losses when fiscal and opportunity costs are taken into account. Claims by the government that the reset will add £9 billion to GDP in the long run (in any case not a large figure in the context of a budget deficit of around £150 billion) are pure fantasy.

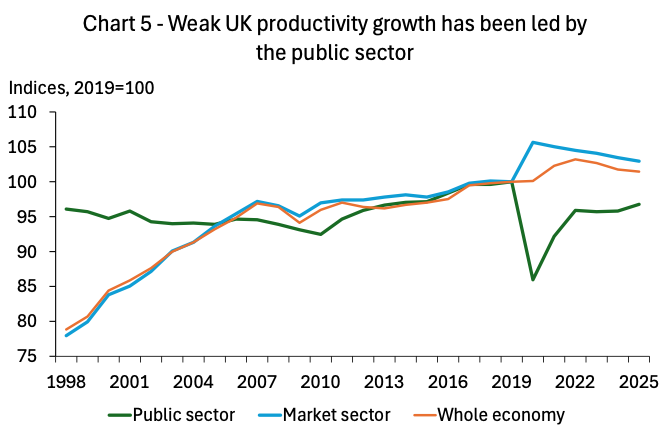

Barring a remarkable change of heart, it is likely to be for a future government to grasp the nettle of serious structural reforms and try to boost the UK’s weak productivity growth. Among other things, this will mean major reforms of the public sector, which has been the main problem area – public sector productivity is 3-4% lower now than it was in 2019 (see Chart 5). Without tackling this, fiscal problems are likely to continue to recur.

Related