Nik Storonsky, the billionaire founder of Revolut, has reportedly left the UK and become tax resident in Dubai – a move that could save him more than £3 billion in UK capital gains tax. His departure raises a larger question for the UK tax system: could we have stopped him leaving? Either with the carrot of a more competitive tax system, or the stick of an exit tax?

The £3bn exit

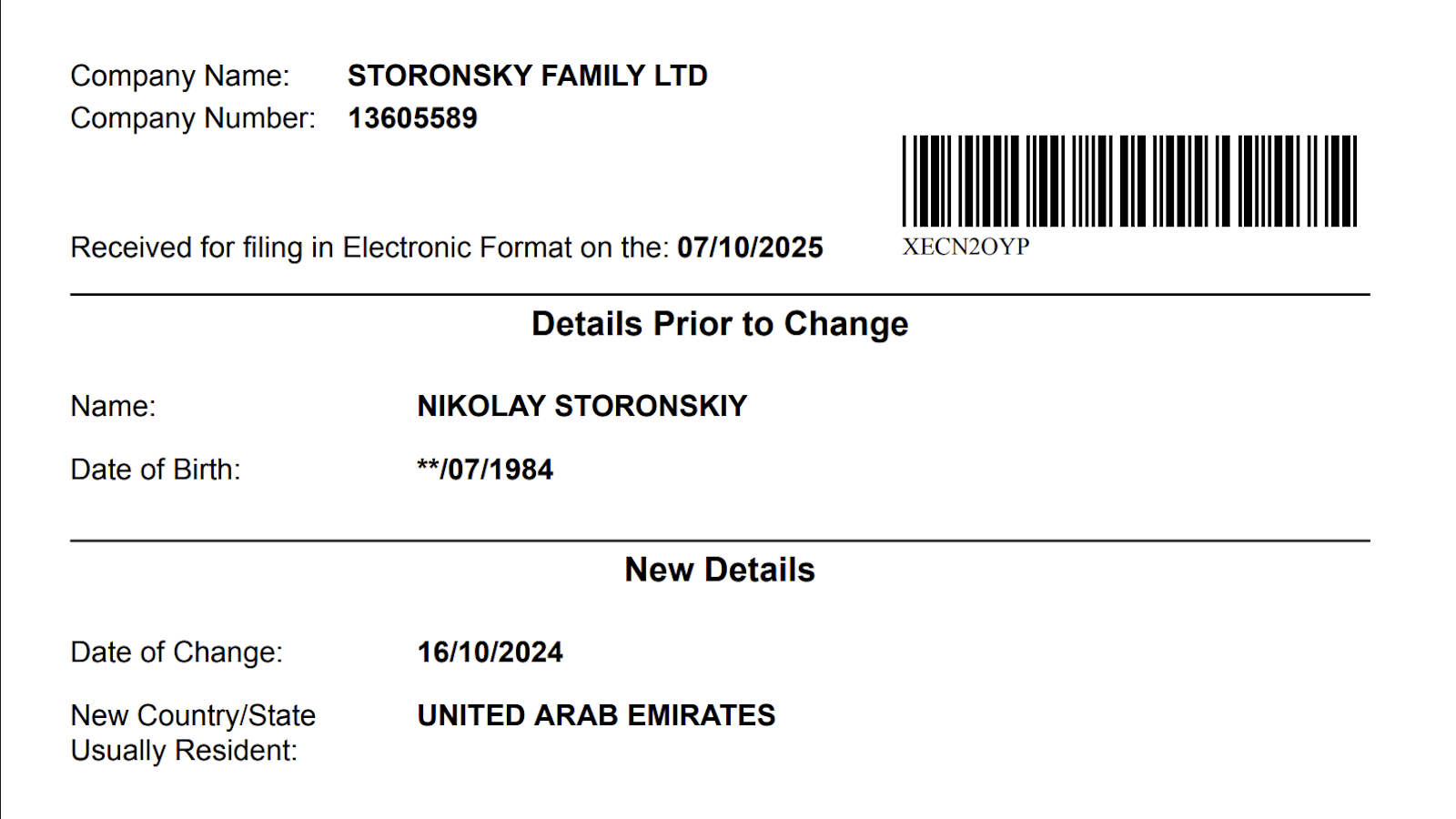

As reported, Nik Storonsky, the founder of Revolut, updated a Companies House entry to show his residence shifting from the UK to the United Arab Emirates.

Revolut is expected to list in the near future, with the most recent funding round suggesting its market capitalisation would be around £55bn. Mr Storonsky owns about 25% of the business – so his stake is worth about £14bn (and potentially more under an incentive deal if the value of the business grows significantly).

If he’d remained UK resident then he would have been taxed at 24% on his capital gain when/if he sold shares – with a CGT liability of up to £3.4bn if he sold them all. To put this in context, that’s about a quarter of the UK’s total capital gains tax revenue in any one year.

Mr Storonsky would also have paid UK income tax at the dividend rate of 39.35% on dividends on his shares.

The UAE has no capital gains tax or income tax. So Mr Storonsky has plausibly saved over £3bn by leaving the UK.

The question is how we should think about this, and whether we should change our tax policy – either reducing tax to convince people like Mr Storonsky to stay, or creating exit taxes to make it more expensive for them to leave.

There are at least three different ways to view this – but no easy answers:

1. This shows the UK is not competitive

In a very real sense this is true. For someone expecting to make a large capital gain, or receive a large amount in dividends, the UK is completely uncompetitive against the UAE and other countries that have zero capital gains tax and/or zero income tax.

This is, however, a proposition that only a small island or an oil-rich city-state like Dubai can offer. No large developed economy has zero income tax or zero CGT – it can’t be done.

Merely cutting our income and CGT wouldn’t change the dynamic – we’d have to match (or almost match) the UAE’s proposition.

Could the UK abolish CGT?

Capital gains tax is expected to raise £20bn in 2027/28 – a substantial sum. There would undoubtedly be dynamic effects from abolishing the tax – abolition would cost less than £20bn, as increased economic activity caused additional revenue from other taxes.

In the short term these effects would be very large, as people who’d sat on assets with large unrealised gains took the opportunity to dispose of them. However the evidence suggests that there would be very limited positive effects beyond this.

The key reason is that UK assets are mostly held by institutional and foreign investors who aren’t subject to UK CGT. The wealthy generally diversify their holdings, and so only a small proportion of their assets will be UK assets. This puts a low cap on the ability, even in principle, of capital gains tax policy to materially impact the UK economy.1

Another reason: the rate of capital gains tax is too low to have large incentive effects. If the rate of capital gains tax was 98% (say) then very high then a rate cut absolutely would pay for itself, but a rate of 24% means that is very unlikely.

So there’s limited upside. There is, however, a considerable downside to abolishing capital gains tax, aside from the c£20bn of immediately lost revenue.

Without CGT, people have a huge incentive to avoid tax by shifting what is really income into capital gains. The Beatles did it in the 1960s. The wealthy continued to do it in the 1970s (which is one reason why those apparently high 98% income tax rates in fact raised little). Private equity firms do it today. There’s lots of evidence that changes to CGT rates exacerbate these effects, and CenTax has plausibly estimated that abolishing CGT would reduce income tax revenues by between £3bn and £12bn.

Many economists therefore believe that capital gains taxes shouldn’t exist in principle, but have to exist in practice to protect income tax.

Those (non-tax haven) countries that don’t have a capital gains tax usually defend against the potential loss of income tax by creating a series of special rules that realistically amount to a rather messy and complex capital gains tax. A New Zealand law firm has written a helpful explanation of the New Zealand approach, and the title says it all: “Just admit it already New Zealand, we do have capital gains taxes“.

The “competitiveness” argument is, therefore, not coherent – eliminating capital gains tax would cost c£25bn – about 1% of GDP, with little upside.

That’s not to say there aren’t other things we can do to make our capital gains tax system encourage investment. We could stop taxing illusory inflationary gains. We could end the anomalous and unprincipled prohibition on deducting capital losses from ordinary income.2

There are also other ways we could change the tax system to encourage investment; we could abolish stamp duty on shares. We could reform corporation tax. We could abolish business rates and stamp duty land tax and replace them with a modern land value tax.

However it’s doubtful that any of these would have persuaded Mr Storonsky to stay in the UK – none of them would have materially changed his £3bn capital gains tax bill – indeed the most realistic CGT reform would increase it..

Even if we reduced CGT to 5% (likely at an overall cost of £20bn+), migration would still have saved Mr Storonsky £600m of tax. I suspect most people would migrate to save £600m.

We can’t compete with the UAE.

2. This shows we should change the law and tax exits

This argument goes: it’s unfair that someone can build a valuable business in the UK, leave the UK, and then never pay tax on what is (realistically) remuneration for their work during the time they spent in the UK. “Unfair” both from a vertical equity standpoint (why should Mr Storonsky pay less tax on billions than a cleaner pays on minimum wage) and a horizontal equity standpoint (why should Mr Storonsky pay less tax than someone in an identical position who chooses to remain in the UK?).

It also seems undesirable for the UK to have a tax system that actively encourages wealthy people to leave.3

Many countries try to prevent these outcomes with “exit taxes”.

Typically how this works is that, if you leave the country, the tax rules deem you to sell your assets now, and if there’s a gain then you pay tax immediately (not when you later come to sell). Often you can defer the tax until a future point when you actually sell the assets or receive a dividend.4 And if your new home taxes your eventual sale, then your original country will normally credit that tax against your exit tax. Actual implementation is (inevitably) more complicated, but today almost every large developed country in the world5 has an exit tax:

- The US has an exit tax for people leaving the US tax system by either renouncing their citizenship, or giving up a long-term green card. Unrealised gains in their assets, including their home, become subject to capital gains tax at the usual rate, with no deferral – it’s perhaps the harshest exit tax in the world.

- Australia has an exit tax – unrealised gains are taxed at your normal income tax rate for that year. There is a complicated option to defer.

- Canada has an exit tax on unrealised gains; there’s a deferral option, and your home isn’t taxed at all.

- France has an exit tax at an effective rate of 30% on unrealised capital gains, with a potentially permanent deferment if you’re moving elsewhere in the EU, or to a country with an appropriate tax treaty with France.

- Germany has an exit tax approaching 30% on unrealised capital gains. If you’re moving elsewhere in the EU you used to get a deferral; from the start of 2022 you instead have to pay in instalments over seven years.

- Spain has an exit tax with a deferral option (if you’re moving within the EU or to a country which has a double tax treaty with Spain).

- The Netherlands has an exit tax on private company holdings, pensions and some other savings products, with an option to defer within the EU, and in other countries if security is provided.

- New Zealand’s quasi-capital gains tax regime is now adding an exit tax.

The only two large developed countries that don’t have an exit tax are the UK6 and Italy.

Exit taxes are greatly complicated by EU law, which imposes numerous (and vague) restrictions on how exit taxes can work. That facilitates loopholes – France, Germany and others are engaged in a long term battle of attrition with the EU over how far their exit taxes can go.

So one new freedom the UK has post-Brexit is the ability to impose our own exit tax that the CJEU can’t stop.78

There are, however, some important arguments against:

- The principled argument: tax competition is an unalloyed good. People have a right to live where they wish and shouldn’t be forced (directly or indirectly) to stay in the UK.

- The practical argument: people (like Mr Storonsky) will be less willing to come to the UK if we have an exit tax.9 This must be true; however when most other large developed countries do have an exit tax, it’s unclear what their options are.10

- A corollary of that: the existence of an exit tax will prompt entrepreneurs to leave the UK at an earlier point than they do now. Take Mr Storonsky as an example. If we had an exit tax then perhaps he would have left the UK in 2017 when the business was valued at around £50m. He would have had a roughly £3m exit tax liability which he would have deferred. Then at the eventual listing he would have made billions of pounds tax free, and then finally paid his deferred exit tax. In this scenario, the exit tax made very little revenue. We missed out on years of income tax on his remuneration and dividends. And wider consequences: Revolut would plausibly have had less activity in the UK if its founder and CEO wasn’t based here.

- A more immediate practical concern: implementing an exit tax is a high risk endeavour. If the belief takes hold that the Government will introduce an exit tax then people will leave before the exit tax bites; even speculation about exit taxes can be economically damaging. Norway recently introduced an exit tax to protect its wealth tax – and it experienced an immediate wave of exits.11

- An exit tax requires valuing illiquid assets like private company shares – that’s notoriously difficult and subjective. Although, unlike a wealth tax, an exit tax with deferral enables valuation with the benefit of hindsight12, and mostly won’t create liquidity issues.13

3. Exiting entrepreneurs is a price worth paying

This argument goes something like:

- It’s a shame that Mr Storonsky has left the UK, but he created a valuable UK business, and that greatly benefits the UK in terms of economic growth, jobs, and (perhaps most importantly) the service Revolut provides its customers.

- Those benefits are far more important (quantitatively and qualitatively) than a few billion pounds of capital gains tax revenue. Mr Storonsky might not have ever come to the UK if he hadn’t viewed the UK as an open economy. There is evidence that “star” inventors’ location choices are heavily influenced by top tax rates.

- An exit tax would change all that. A signal that the UK no longer welcomes entrepreneurs, but seeks to trap them. Worse, it would be seen by many as retrospective taxation – they arrived in the UK expecting tax to work in a particular way, and now that changes without warning.14 People would worry about further quasi-retrospective changes.

This is a rather boring and defeatist argument for the status quo. That doesn’t mean it’s wrong.