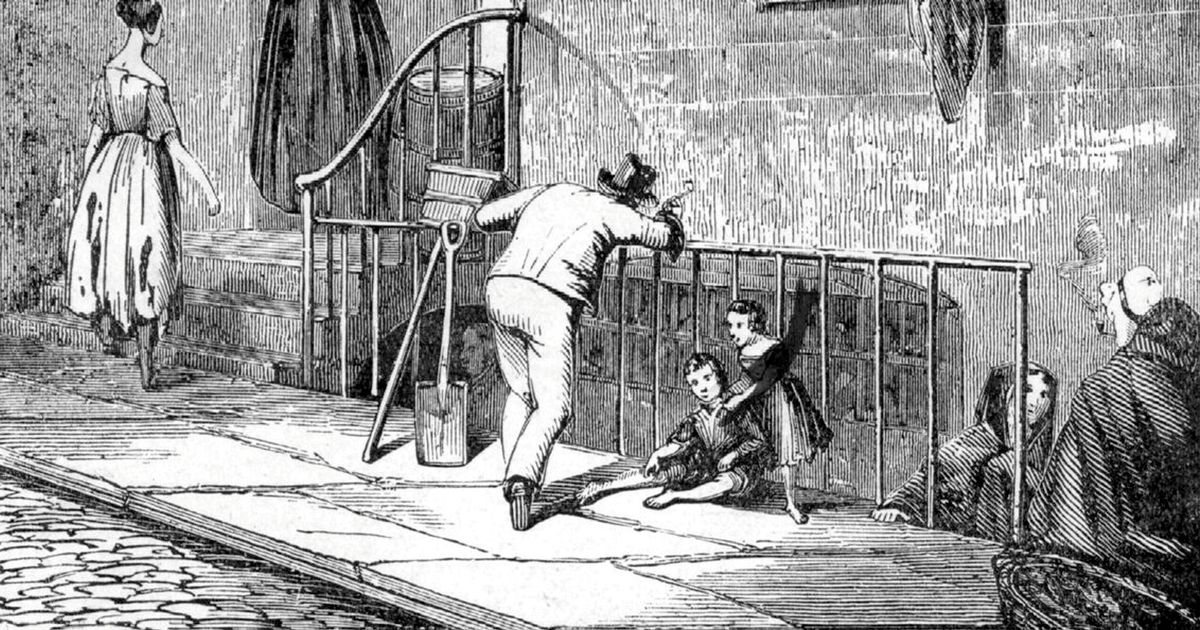

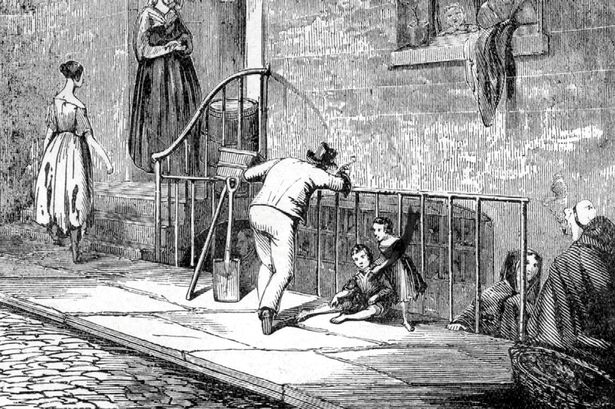

The data was described as “a big surprise” by researcher An 1838 print showing people in and outside a terraced house in Manchester

An 1838 print showing people in and outside a terraced house in Manchester

Wealthy doctors, engineers and working class people all lived in the “slums” of Victorian era Manchester, new research has revealed.

The study by Cambridge University Historian, Emily Chung, used data from a digitised 1851 census to precisely map where people from different social classes lived in the city.

Her study has shown that work, shopping, church and the pub may have done more to keep different classes apart than “residential segregation” in 1850s Manchester.

For years, historians have used Marxism co-founder, Friedrich Engels’ observation of “rampant inequality” during his visit in 1842 as their basis of understanding what life was like in Victorian Manchester.

Engels described a scene of different classes residing in separate parts of the industrial city, proclaiming it to be a commercial core encircled by “unmixed working-peoples” quarters, then the “middle bourgeoisie” and the upper classes in the leafy outskirts.

However, Chung’s revelations have now introduced a new perspective on the matter.

Her findings, published in The Historical Journal, shows that many middle-class Mancunians lived in the same buildings and streets as working-class spinners and weavers.

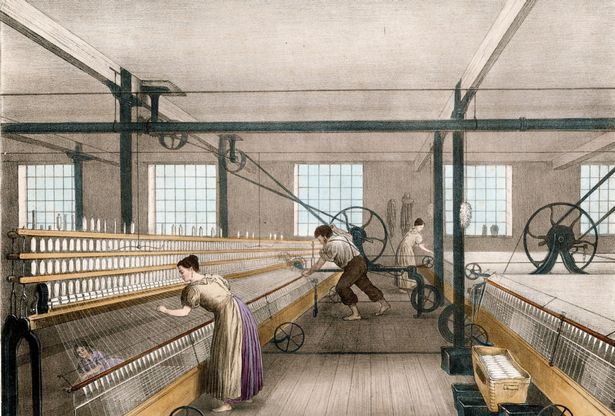

This period, Manchester was the centre of the cotton industry and referred to as ‘Cottonopolis’

This period, Manchester was the centre of the cotton industry and referred to as ‘Cottonopolis’

The study shows that more than 60% of buildings housing the wealthiest classes also housed unskilled labourers. And more than 10% of the population in Manchester’s “slums” belonged to wealthier employed classes.

Ms Chung, a PhD researcher at St John’s College, Cambridge, said: “Manchester’s wealthier classes did not confine themselves to town houses in the city centre and suburban villas, as we’ve been led to believe.

“I found doctors, engineers, architects, surveyors, teachers, managers and shop owners living in the same buildings as poor weavers and spinners.

“Segregation in cities remains a major concern in many parts of the world, including Britain, so understanding what people experienced in Manchester, one of the world’s first industrialised cities, is really important.

“It teaches us that where we live matters, but other factors can be even more influential. How people work, shop and relax divides social groups and can even make them invisible.”

She utilised ordnance survey maps, commercial directories and the 1851 census to link individual people to their specific residential address.

Ms Chung spent eight months pinpointing buildings using known landmarks, including pubs, to guide her, mapping up to 700 buildings per day – which AI technology isn’t yet capable of doing accurately.

She found that the commercial district to Manchester’s south-west was “significantly more socially diverse” than residential zones of the city to the north and east.

But even in “notorious” Ancoats – the main working-class slum which appalled Engels – around 10% of the population belonged to the wealthier employed classes.

Across the city, the working-class represented an average of 79.3% of the population. When she zoomed in on individual buildings, she found that over 60% which housed the wealthiest occupational classes also housed unskilled labourers.

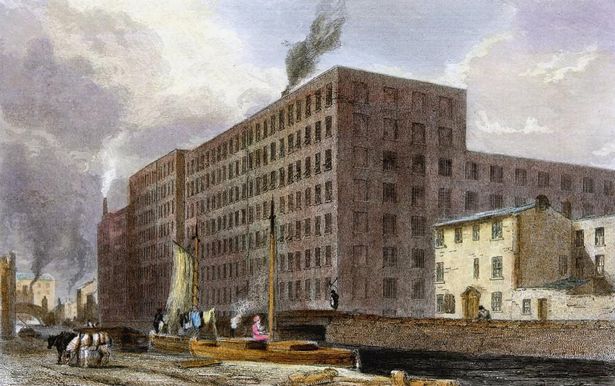

Union Street Mill, Ancoats, Manchester

Union Street Mill, Ancoats, Manchester

Ms Chung said: “This was a big surprise.

“I started with the city centre and I thought the pattern might end there but as I moved onto the next part of Manchester, I kept finding this mixing.

“The most exciting moment was discovering that one in 10 people living in Ancoats, the notorious working-class slum, were middle-class.”

She added: “Middle-class Mancunians might have seen their homes as stepping stones to something better.

“But architects and shop owners also valued the convenience of living close to where they worked. Commuter trains weren’t popular yet.”

In the first half of the 19th Century, she says Manchester couldn’t build houses fast enough to keep up with its booming population.

Ms Chung said: “Manchester grew almost organically with very little regulation and developers were determined to make maximum profit from as little land as possible.

“Manchester’s housing experiment stacked multiple households one on top of another.

“Different classes were living so close together but walls, ceilings and different routines minimised interaction between them.”

She explained that the middle and upper classes had “flexible” access to shops and markets, but factory workers often had to wait for their wages on Saturday evenings before they could buy food.

Ms Chung said: “While Victorian London and Liverpool bustled with daytime activity, Manchester’s public spaces were almost deserted.

“Its streets were rarely occupied by weavers and doctors at the same time.”

She says Manchester’s middle classes were increasingly drawn to church while the city’s 600 pubs had a far greater pull on the working classes.

Churches no longer distributed relief as they had under the Old Poor Laws and public services made many poor people feel ashamed.

Even when the poor did attend, Ms Chung says many churches and chapels deliberately kept different classes apart.

Morning services rented out pews on an annual basis, catering towards the middle and upper classes, while afternoon or evening services were more likely to be frequented by the working class who couldn’t afford regular rents.

But Ms Chung says pubs offered “more welcoming and affordable” respite for working-class Mancunians.

However, as soon as they went outside the city’s police were ready to re-enforce class segregation.

Ms Chung said: “Even small groups of working-class men were made to disperse by officers on rotation.

“They were determined to keep the city’s middle- and upper-class dominated public realm clear, clean and calm, so they forced the working poor out of sight into more neglected parts of the city.

“What the Victorians ‘thought’ was happening in Manchester still matters, but comparing these perceptions against concrete geographic patterns means we can reconstruct life in the city more accurately.

“Then we can understand how those perceptions arose.”

Ms Chung says one mystery that rains is how multiple families from different classes shared outdoor “privvy” toilets.

She said “Annoyingly, this isn’t something that people wrote about at the time.

“I suspect that the middle classes still used chamber pots so they weren’t so reliant on shared privvies.”