Teenage girls love Westfield shopping centre: they can hang out playing truant, or linger after school and weekends and be pretty invisible. They ride the escalators, drink milkshakes, and look out for good-looking boys to flirt with.

And at Westfield there are boys lying in wait. Teens are there, in small groups, sent to target girls of around 13 who are hanging out with no adults in tow. This is “first-stage seduction” — a tried-and-tested technique — and I’ve seen it first hand, as a group of three boys bought ice creams for a couple of girls who they had obviously just met. The girls were giggling and coy and lapping up the attention, clearly in awe of the boys. Then the lawyer I was with discreetly pointed out the older Asian men hanging around the peripheries, watching the interactions.

Stratford’s shopping centre has been a notorious grooming hotspot for years. It’s easy to be anonymous in the cavernous mall, and security guards have spoken about how hard it is to keep an eye on suspicious individuals as they disappear into the front and out of the back of many of the large department stores. “It’s not illegal for teenagers to have coffee together, or to flirt, go into the cinema, or try on trainers,” one police officer told me. “What are we supposed to do?”

By now, everyone is familiar with the grooming gang scandal. But few people realise how serious the problem is in London — and those who do are very reluctant to call it out. As we are only now discovering, the capital’s politicians, police and social workers are just as guilty as those pilloried Up North for conspiring to keep this growing threat out of the public eye. Rather than exposing and stopping the trafficking of girls, they have dodged the issue by saying this isn’t sexual exploitation: instead they say the girls are criminals too. They’re being recruited for “county lines”, to move and supply drugs.

Sadiq Khan, Mayor of London, produced exactly this deflection at the beginning of the year. Asked directly, by Susan Hall, leader of the Conservatives in the London Assembly: “Just how many grooming gangs have we got in London?”, Khan replied with an unhelpful: “The situation in London in relation to young people being groomed is different to other parts of the country.”

There followed a lengthy and revelatory exchange, during which Khan managed to dodge the same question nine times. Eventually, he did manage a response — of sorts. “What we have in London,” he said, “is young people being groomed, your words not mine, to be using county lines.”

Khan’s response is scarcely credible on many levels, especially since the grooming of girls in London has been going on for decades and if one whistle-blower is to be believed, it is at “catastrophic” levels. Jon Wedger is a former Metropolitan Police officer with more than 25 years experience investigating child sexual exploitation. Back in 2006, Wedger submitted a list of 50 youngsters who had been groomed and sexually abused in the capital, providing details such as the car-registration numbers of the perpetrators. But he was told to back off by social services, and even a large children’s charity, because he was generating “extra work”.

Wedger tells me that nothing has changed. The gangs are still operating; the authorities are in denial. And the methods of procurement are just as we’ve seen countrywide. “The idea that they aren’t prevalent with the similar MO in London is just staggering to me,” he says. While the city is target-rich, Wedger’s focus has been on care homes. “Girls are being collected by men outside children’s homes in fancy cars, and being taken to a brothel. In the meantime, the police are looking for kids cycling around London dealing drugs for the big players, and the girls are ignored.”

The authorities are, quite literally, turning a blind eye to the problem. As late as 2018, Metropolitan Police officials claimed they were unable to address concerns about grooming gangs because “the terms ‘rape gangs’ and ‘grooming gangs’ are not legally recognised and do not appear in MPS policy”.

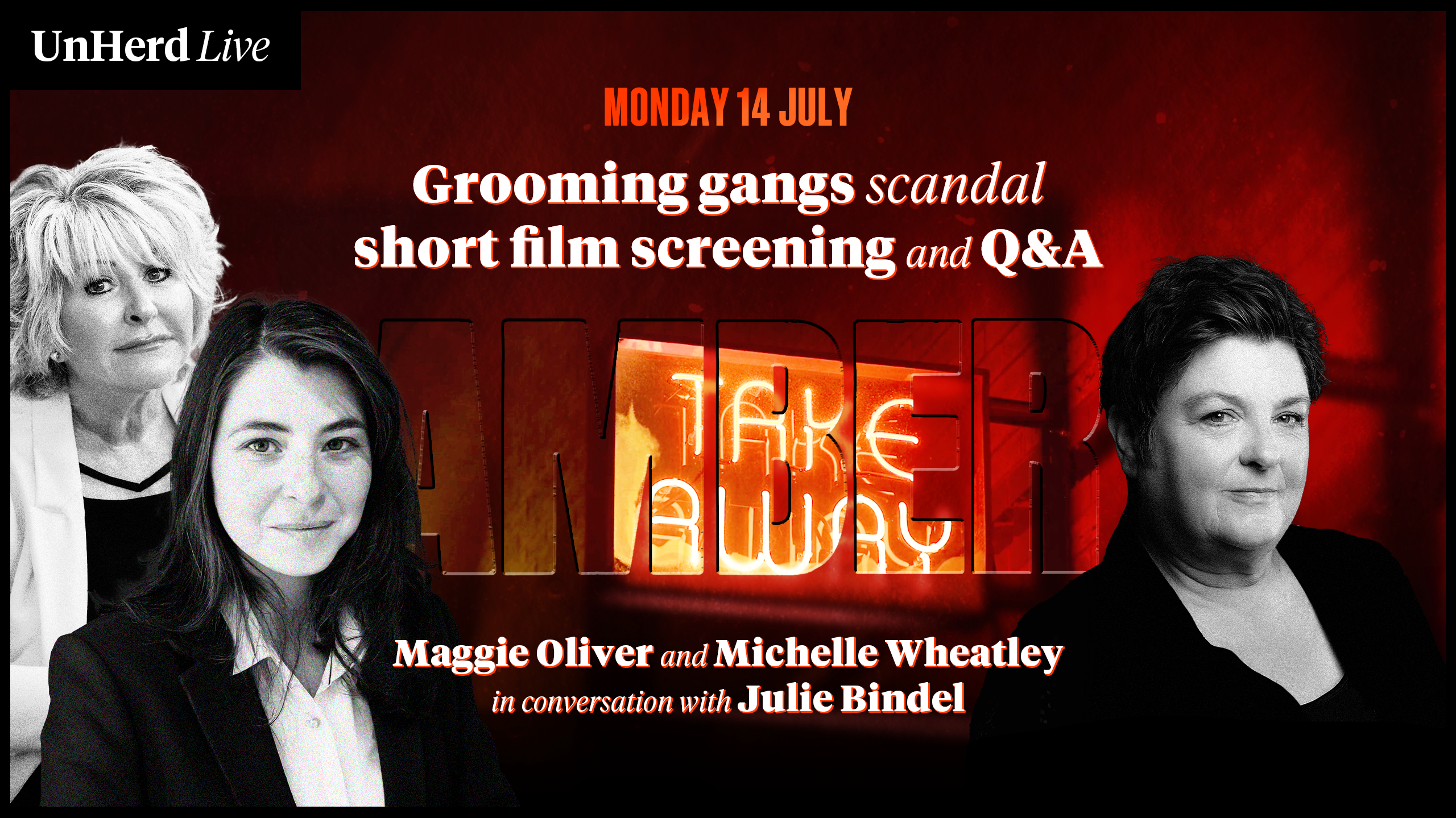

UnHerd Live: The grooming gangs scandal: Short film screening and Q&A

UnHerd Live: The grooming gangs scandal: Short film screening and Q&A

And yet, we know for a fact that Arshid Hussain, central to the infamous Rotherham grooming cases, took one of his victims to London, where she was sexually assaulted by three men as repayment for Hussain’s debts. And Mohammed Karrar, convicted in 2019 in the Oxford grooming scandal, trafficked his victim repeatedly to Paddington Station, selling her to other men. We also know from Professor Alexis Jay’s 2021 Independent Inquiry into Child Sexual Abuse that grooming gangs in London exist and operate along the classic “boyfriend model” of procurement, just as they do in the North. But at every mention of the situation in London, Sadiq Khan insists on using “county lines” terminology, instead of acknowledging the existence of rape gangs.

Michaela Addison has worked closely with victims and survivors of grooming gangs in London, and she is appalled at the use of what she describes as “sanitised language” to describe these crimes. It’s perfectly understandable why the mayor might do this, she explains: “if you can’t name it, the problem doesn’t exist”.

“If you can’t name it, the problem doesn’t exist”.

But the problem does exist. Just ask Katie. She was victimised twice: once by the grooming gangs, and then by the police. “I fell in love with Dan, big style,” she tells me, describing her Afghan boyfriend. “And by the time I realised he was a psycho, I was trapped, I was living partly with him, and partly with my foster carers, and his friends would come round and take me to flats where dirty old men would queue up to abuse me.” Katie was 15 years old at the time, and only called the police when it became clear she was in real danger. “I saw Dan with another bloke and he had what I thought was a gun. I knew they were dealing drugs, they used to give me some when I’d seen enough men, but it was the gun that really scared me, so I went into the police station and told them everything.”

However, the police totally ignored her claims of sexual violence and pimping, honing in only on the allegations about weapons and drugs. “As soon as I mentioned the gun, I could tell by the questions they were asking me that all they wanted to know was, ‘Where is this gang, who were the main drug dealers, where do they stash the gear?’”

Katie, now in her 20s, knows she will never see justice for what happened to her. “It’s all about county lines,” she tells me. “The girls are worth less than the gear.”

When I approached Sadiq Khan’s office for comment last month, this dismissive response found its echo: “The Mayor and the Met remain vigilant and will continue to do everything they can to protect children in the capital from violence and exploitation in all its forms, such as offending by grooming gangs,” but that in London, “in particular, we are dealing with “county lines”… These gangs exploit children and often use coercion, intimidation and violence, including sexual violence.”

The trouble is, to use such language implies that the girls are complicit in criminal activity, rather than being the victims of abuse and coercion. It also avoids the fact that the term “grooming gangs” is heavily racialised.

Susan Hall has also been deeply troubled by Khan’s insistence over many months that grooming gangs only exist in London in the context of county lines. “Given how widespread this appalling criminality has been in other towns and cities across the country,” she says, “it is impossible to think that grooming gangs like those uncovered in Rochdale and many other areas have not also operated in a city as big as London.”

The evidence backs this up: Sir Mark Rowley, the Metropolitan Police Commissioner, is on the record denying that London has a grooming gang problem; but when presented with the evidence, admitted that there is a “steady flow” of live multi-offender child sexual exploitation investigations, and a “very significant” number of cases that would need to be reinvestigated as a result of the current review.

“This is exactly what Sadiq Khan has done,” Maggie Oliver, a former police officer and anti-grooming gangs campaigner, tells me. “He denied the problem for as long as he can, and then being forced to at least partially admit that it’s going on but by using different language to describe it.”

None of this is to dismiss the importance of the county lines angle. It is serious, widespread and warrants significant police attention. But the reluctance of the Met and the Mayor’s Office to discuss grooming gangs — to even use the term, let alone investigate — means that rape victims are, as usual, the ones paying the price.

All the while, carers and whistleblowers are having to go back to basics in order to convince people that these girls are actually victims of grooming gangs. One sexual health worker I spoke to told me that in many cases, the police simply weren’t interested. There is, she told me, one notorious McDonald’s in South West London where gang members like to go to pick up girls. She and her colleague had reported, no fewer than half a dozen times, “information that the girls have told us about themselves being directly abused, and, in one case, two very young sisters being targeted and raped by the men”. But each time she followed up her call, she discovered that none of the previous reports had been logged. “We had given them as much information as we had, including in one case a car registration of one of the perpetrators, but they have mysteriously ‘lost’ all of this information.”

As Wedger told me: “What you don’t look for, doesn’t exist.”

But for how long can the authorities keep looking the other way? Already, news is starting to break. Only this week, a national newspaper confirmed what our investigation suspected. Sadiq Khan had access to and is known to have read several separate reports by His Majesty’s Inspectorate of Constabulary and Fire & Rescue Services, from 2016-2025, which identified six victims of these gangs. These documents also outlined the dreadful details of the abuse endured by these girls — some as young as 13. Some of the girls were raped by multiple men in London hotel rooms after being plied with drugs and alcohol. Chris Wild, an author and care-home consultant, has described the problem as “more catastrophic in the capital than anywhere else in the country”. We now know that Khan knew about it, and still he could only obfuscate and point to “county lines”.

The really shocking thing, though, is that we have been here before. While Khan keeps his own counsel, Keir Starmer’s grooming gang inquiry, which was resisted for so long, is already falling apart. Members of the initial panel have claimed that the terms of the investigation are already being watered down, and cite “a disturbing conflict of interest” regarding the identities of two possible chairs. Fiona Goddard, a member of the panel and a grooming gang victim, sent a searing note of resignation, in which she echoed a refrain which is now too all familiar: “I’m further concerned by the condescending and controlling language used towards survivors throughout this process who have had to fight every day just to be believed.”

As the scandal in London grows, the process for bringing institutions to account is in complete disarray. And last night, a third member of the Starmer inquiry resigned: all three women are victims; all three are sick of the continued cover-up. The question for the rest of us is: how can there ever be justice for the abused girls, and retribution for the perpetrators, if public servants such as Khan remain in denial?