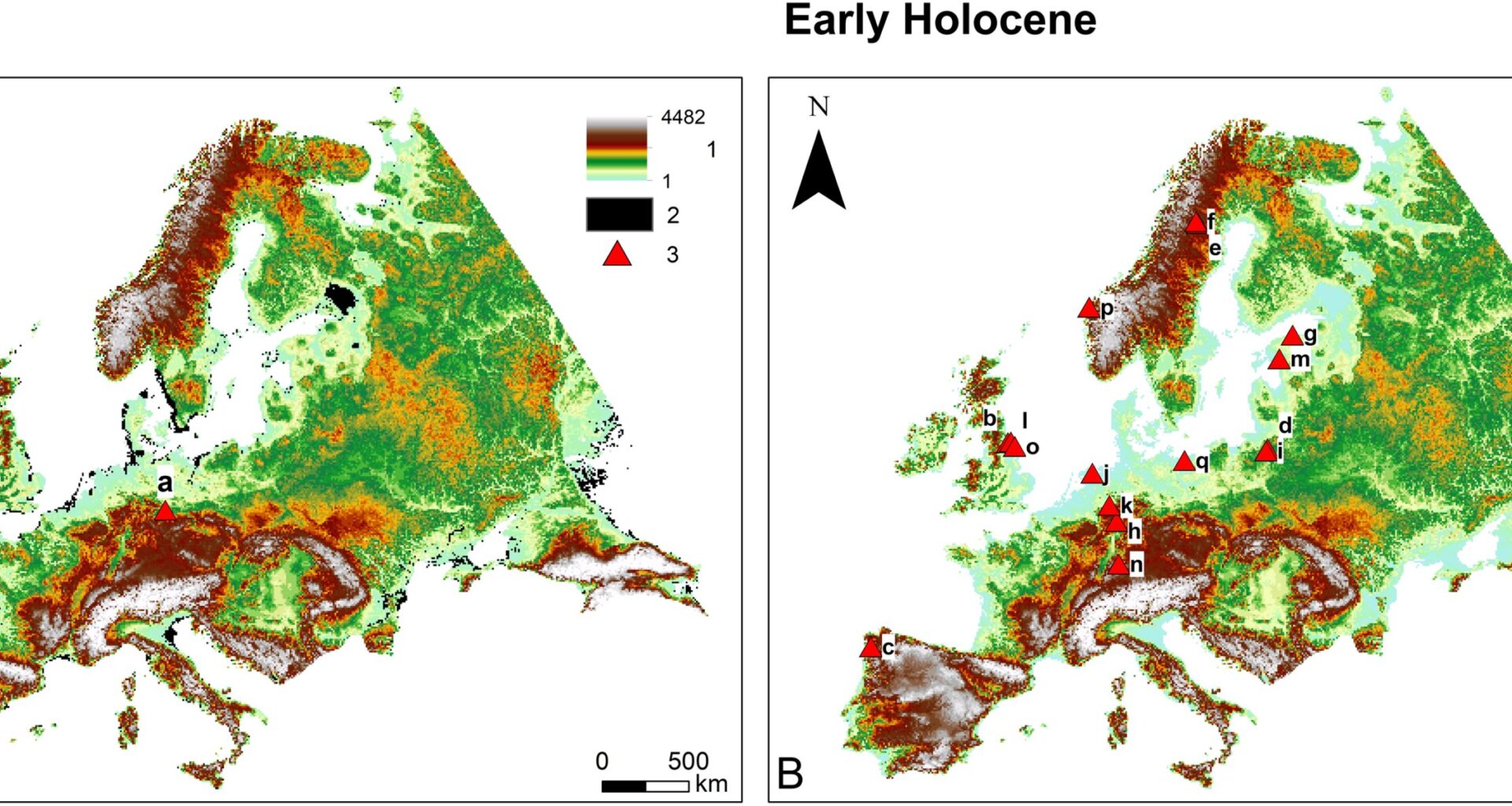

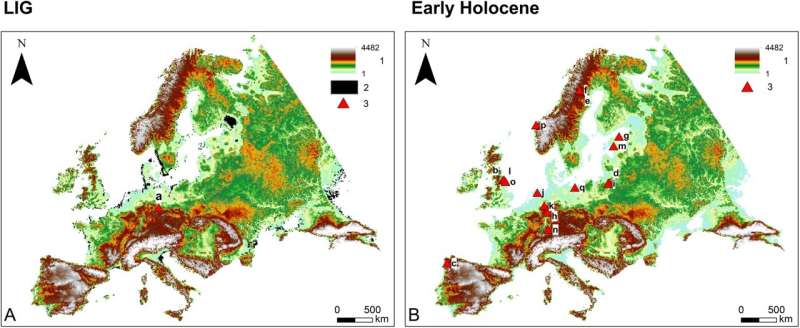

LIG (A) and Early Holocene (B) study area. Legend: 1–Elevations (in meters above sea level, m a.s.l.); 2–No data; 3–Case studies indicating possible vegetation burning by LIG and Early–Middle Holocene hunter-gatherers. List of case studies: a–Neumark-Nord; b–Bonfield Gill Head; c–Campo Lameiro; d–Dudka Island; e–Dumpokjauratj; f–Ipmatisjauratj; g–Kunda-Arusoo; h–Lahn valley complex; i–Lake Miłkowskie; j–Meerstad; k–Mesolithic site at Soest; l–North Gill; m–Pulli; n–Rottenburg-Siebenlinden sites; o–Star Carr; p–Vingen sites; q–Wolin II. Credit: PLOS One (2025). DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0328218

Imagine Europe tens of thousands of years ago: dense forests, large herds of elephants, bison and aurochs—and small groups of people armed with fire and spears. A new study shows that these people left a much clearer mark on the landscape than previously assumed.

Using advanced computer simulations, an international research team, including researchers from Aarhus University, has investigated how climate, large animals, fire and humans affected Europe’s vegetation during two warm periods in the past. By comparing the results with extensive pollen analyses from the same periods, the researchers have calculated how the different factors shaped vegetation cover.

The conclusion is clear: Both Neanderthals and the later Mesolithic hunter-gatherers had a strong impact on vegetation patterns in Europe—long before the advent of agriculture.

The findings are published in the journal PLOS One.

“The study paints a new picture of the past,” says Jens-Christian Svenning, professor of biology at Aarhus University and one of the researchers behind the study, which was undertaken in collaboration with colleagues in archaeology, geology and ecology from the Netherlands, Denmark, France, and the UK.

“It became clear to us that climate change, large herbivores and natural fires alone could not explain the pollen data results. Factoring humans into the equation—and the effects of human-induced fires and hunting—resulted in a much better match,” says Svenning.

Humans displaced large animals

The researchers focused on two warm periods in the past.

One is the Last Interglacial period, around 125,000–116,000 years ago, when Neanderthals were the only humans in Europe. The second period is the time just after the last ice age, the Early Holocene, 12,000–8,000 years ago, at which time Mesolithic hunter-gatherers of our own species, Homo sapiens, lived here.

During the Last Interglacial period, Europe was home to a rich and varied megafauna, with elephants and rhinoceroses living side by side with bison, aurochs, horses and deer.

In the Mesolithic, the picture was different: The largest species had disappeared or their populations had been greatly reduced in size—due to the general loss of megafauna that followed in the wake of the spread of Homo sapiens across the globe.

New view of prehistoric man

“Our simulations show that Mesolithic hunter-gatherers could have influenced up to 47% of the distribution of plant types. The Neanderthal effect was smaller, but still measurable—approximately 6% for plant type distribution and 14% for vegetation openness,” says first author Anastasia Nikulina.

The human-induced effects on vegetation included both fire effects—burning of trees and shrubs—and a previously overlooked factor: the hunting of large herbivores.

“The Neanderthals did not hold back from hunting and killing even giant elephants. And here we’re talking about animals weighing up to 13 tons. Hunting also had a strong indirect effect. Fewer grazing animals meant more overgrowth and thus more closed vegetation. However, the effect was limited, because the Neanderthals were so few that they did not eliminate the large animals or their ecological role—unlike Homo sapiens in later times,” says Svenning.

Nikulina and Svenning both believe that the results offer a new perspective on the role of our ancestors in the natural landscape. In fact, it challenges the notion of an untouched landscape in Europe before agriculture came along:

“The Neanderthals and the Mesolithic hunter-gatherers were active co-creators of Europe’s ecosystems,” says Svenning.

“The study is consistent with both ethnographic studies of contemporary hunter-gatherers and archaeological finds, but goes a step further by documenting how extensive human influence may have been tens of thousands of years ago—that is, before humans started farming the land,” elaborates Nikulina.

Discover the latest in science, tech, and space with over 100,000 subscribers who rely on Phys.org for daily insights.

Sign up for our free newsletter and get updates on breakthroughs,

innovations, and research that matter—daily or weekly.

Interdisciplinary knowledge behind study

Nikulina highlights the interdisciplinary collaboration—between ecology, archaeology, palynology (knowledge about pollen)—and the development of advanced computer models for simulating past ecosystems as strengths of the study.

“This is the first simulation to quantify how Neanderthals and Mesolithic hunter-gatherers may have shaped European landscapes. Our approach has two key strengths: It brings together an unusually large set of new spatial data spanning the whole continent over thousands of years, and it couples the simulation with an optimization algorithm from AI. That lets us run a large number of scenarios and identify the most possible outcomes,” says Nikulina.

Svenning adds, “The computer modeling made it clear to us that climate change, the large herbivores such as elephants, bison and deer, and natural wildfires alone cannot explain the changes seen in ancient pollen data. To understand the vegetation at that time, we must also take human impacts into account—both direct and indirect. Even without fire, hunter-gatherers changed the landscape simply because their hunting of large animals made the vegetation denser.”

Despite the new study, there are still gaps in our understanding of the early impact of humans on the landscape, says Svenning.

Nikulina and Svenning emphasize that it would be interesting to do computer simulations of other time periods and parts of the world. North and South America and Australia are particularly interesting because they were never populated by earlier hominin species before Homo sapiens, and researchers are therefore able to compare landscapes in the recent past with and without human influence.

“And although the large models paint a broad picture, detailed local studies are absolutely essential to improve our understanding of the way humans shaped the landscape in prehistoric times,” says Svenning.

More information:

Anastasia Nikulina et al, On the ecological impact of prehistoric hunter-gatherers in Europe: Early Holocene (Mesolithic) and Last Interglacial (Neanderthal) foragers compared, PLOS One (2025). DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0328218

Provided by

Aarhus University

Citation:

Neanderthals and Mesolithic hunter-gatherers shaped European landscapes long before agriculture, study reveals (2025, October 23)

retrieved 24 October 2025

from https://phys.org/news/2025-10-neanderthals-mesolithic-hunter-european-landscapes.html

This document is subject to copyright. Apart from any fair dealing for the purpose of private study or research, no

part may be reproduced without the written permission. The content is provided for information purposes only.