The U.S. stock market has climbed in recent months, fueled by economic optimism and improving corporate earnings. But there is one fly in the ointment—the U.S. labor market. Recent data have raised concerns that a hiring slowdown could tip the economy toward recession.

Given that consumer spending accounts for almost 70% of U.S. gross domestic product, any softening in employment has direct implications for the strength of the overall economy and for corporate earnings growth. So, how worried should investors be?

Deteriorating jobs data

The most widely followed measure of labor market health is nonfarm payrolls, and payroll growth has been deteriorating steadily since mid‑2021. Net job creation dipped into negative territory this past June—the first contraction in over three years.

As of late October, payroll data for September were not available due to the federal government shutdown. But a more useful barometer of labor market conditions is the Kansas City Fed’s Labor Market Momentum Indicator, which combines 24 different labor market series to create a comprehensive, forward‑looking measure.

Broad barometer shows modest but persistent weakness

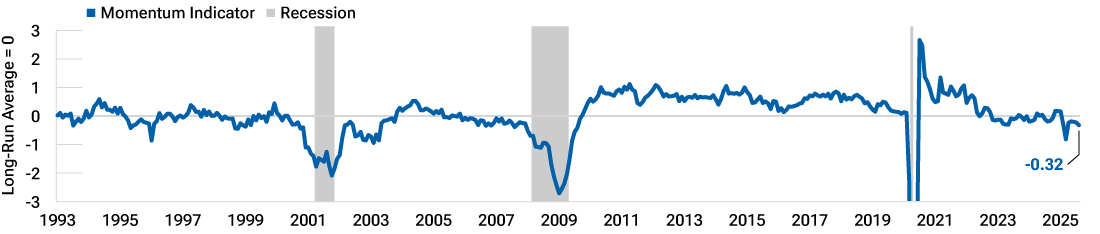

(Fig. 1) Kansas City Fed’s Labor Market Momentum Indicator

January 1993 to August 2025 (pandemic trough not shown).

Sources: Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City/Macrobond.

By aggregating a broad array of inputs—including hiring, wages, job openings, and participation trends—the momentum indicator provides a much richer view of the underlying direction of the labor market than payroll data alone.

The indicator weakened sharply in March but then bounced back (Figure 1). However, it never rebounded into positive territory and has since started to weaken again.

Mitigating factors

While the recent data warrant our attention, several developments suggest that labor market weakness may not be as ominous as it appears.

First, the Trump administration’s aggressive crackdown on illegal immigration has sharply reduced net immigration. Fewer entrants into the labor force means fewer new jobs are needed to keep pace with population growth. So smaller payroll gains may not carry the same negative implications as they would if the U.S. labor force were growing faster.

Recent weakness has been driven by noncyclical areas

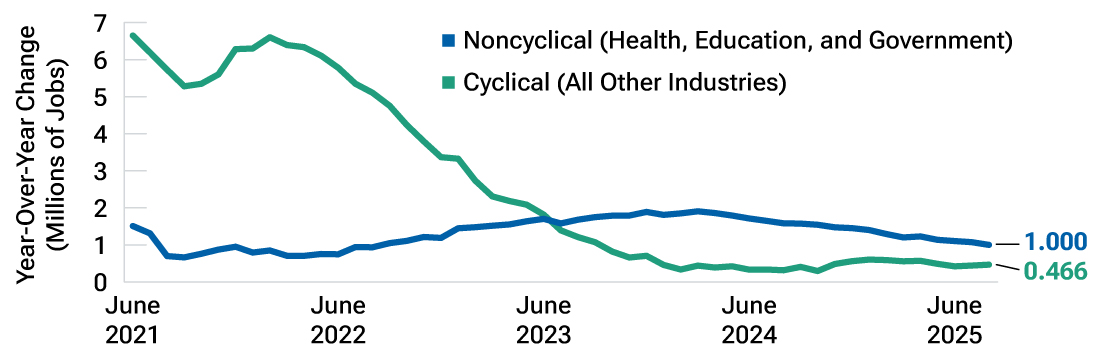

(Fig. 2) Nonfarm payrolls by sector

June 2021 to August 2025.

Sources: U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics/Macrobond.

Second, much of the recent softness in hiring has been concentrated in noncyclical sectors such as health care, government, and education—areas where job growth often reflects sector‑specific dynamics.

If we separate these industries from the more economically sensitive cyclical sectors, we see an interesting pattern: Noncyclical industries were exceptionally strong through 2023 and 2024, masking weakness elsewhere (Figure 2). However, hiring momentum in the noncyclical sectors has cooled over the past several months, making the overall slowdown appear sharper even though cyclical industries have largely stabilized.

Finally, layoffs remain low by historical standards. This suggests that while fewer new jobs are being created, employers are not cutting staff at an accelerating pace. In other words, the labor market appears to be moving from “very strong” to “moderately healthy,” not from “healthy” to “recessionary.”

Conclusion

The U.S. labor market clearly exhibits signs of weakness, but the slowdown appears to reflect normalization after an extended period of exceptional strength, rather than a looming recession.

Accordingly, the T. Rowe Price Asset Allocation Committee continues to maintain a broadly neutral risk posture while keeping a close eye on labor market trends that could influence the broader economic outlook.